Archive for October, 2009

Definition

In a generic sense, the word lottery can cover almost any form of gambling. The word has been applied to any game that offers prizes on the basis of an element of luck or chance in exchange for consideration, that is, something of value. In Canada, the term lottery scheme has come to include all casino games. The term as used in Wisconsin law similarly encompassed casino games, and as a result Native Americans were permitted to have casinos because the state had a lottery.

Thomas Clark’s definition in The Dictionary of Gambling and Gaming is typical (Clark 1987). On the one hand, he views a lottery as “a scheme for raising money by selling lots or chances, to share in the distribution of prizes, now usually money, through numbered tickets selected as winners….” On the other hand, he then adds, “in cards, a game in which prizes are obtained by the holders of certain cards”.

The Variety of Games

Passive Games

The first lottery games set up in the 1960s and 1970 were what are called passive games, in which the buyer is given a ticket with a number preprinted on it. At a later date – perhaps as much as a week (but originally even months) – the lottery organization selects the winning number in some random manner. Usually the organization will use a Ping-Pong ball machine that is mechanical and can be easily observed by viewers. Computers might do a better job in the selection process, but ticket buyers seem to like to see the process of numbers being selected. The ordinary games involved numbers with three, four, five, six, or more digits. Passive games have been operated on monthly, weekly, biweekly, or even daily schedules. These games are described as passive because the player’s role is limited to buying a ticket; the player does not select the number on the ticket. Also, the player must wait for a drawing; the player cannot affect the timing of the drawing.

Instant Games Instant Games

In the case of instant tickets, a finite number of tickets are sold. The state contracts to have all the tickets printed. A number or symbol indicates that the player wins or loses. The symbol is covered by a substance that can be rubbed off by the player; however, the substance guarantees that the symbol cannot be viewed in any way before it is rubbed off. If all of a batch are sold, the lottery is like a bingo organization, as it merely managers the players’ money, shifting it from losers to winners and taking out a fee. The lottery organization is the winner. Unlike passive games, in instant games the player determines the speed of the game; the player activates the game at any time by rubbing off the covering substance.

Numbers Games

In numbers games, players are permitted to actively select their own numbers, which are then matched against numbers selected by the lottery at some later time. Many numbers games are played on a daily cycle. Usually the lottery will have a three-digit number game and a four-digit number game. A pick-three game allows the player to pick three digits, which may be bet as a single three-digit number or in other combination of ways. A machine may also pick the number or digits for the player. However the number is picked and bet, the player is guaranteed a fixed prize if the number is a winning number. For instance, if it is bet as a single number such as 234, and number 234 is selected by a randomizer as the winning number, the player receives a fixed prize of $500 for a one-dollar play. For a pick-four game the prize typically would be $5,000 for a winning number bet “straight-up”.

In these games, there can be no doubt but that the lottery organization is a player betting against the ticket purchaser. These are in effect house-banked games. Some states have sought to improve their odds (even though their payoffs give them a theoretical 50 percent edge over the player) by limiting play on certain numbers or by seeking to adjust the prize according to how many winners there are for the number picked.

Lotto Games

There is a variety of lotto games. In Texas there is a pick-six game. The lotto player selects six numbers or lets a computer pick six numbers from a field of numbers one through fifty. A ticket costs one dollar. A random generator picks six winning numbers. A fourth prize guarantees the ticket holder $3 for having three numbers. A pool amount for third prize is divided among players who have four numbers selected. A second-place pool is divided among players who have five numbers, and a grand prize pool is reserved for players with all six winning numbers. If no player has six winning numbers, the grand prize pool is placed into the grand prize pool for a subsequent game played at a later time. The lotto games gain great attention owing to superprizes that often exceed $100 million – the biggest prize was over twice that much. On 26 April 1989 the Pennsylvania lottery gave a prize in excess of $100 million for the first time (NBC’s Today Show, 26 April 1989). In the early 1990s a multistate lottery awarded a prize of about $250 million.

Video Lottery Terminals

Video lottery terminals are played very much like slot machines. They are authorized to be run by lotteries in several states, including South Dakota, Oregon, and Montana, in bars and taverns. In Louisiana the machines also are permitted but are operated by the state police. Racetracks operate machines under government control in Iowa, West Virginia, New Mexico, Delaware, Louisiana, and Rhode Island. Seven of the Canadian provinces have lottery-controlled machines in bars. They are also at racetracks in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario. Where the machines are operating in large numbers, they usually dwarf other revenues of the lottery.

Lottery Revenues

An overview of lotteries shows that in 1998 traditional (nonlottery machine) ticket sales amounted to $33.9 billion. Of this amount, $18.8 billion (55.4 percent) was returned to players as prizes, and $15.1 billion (44.6 %) was winnings for the lottery. Each resident in the lottery states spent an average of $149.52 on tickets. This represented 0.6 percent of the personal income in the states. Governments retained $11.4 billion (33.7 %) of the money spent on tickets after all expenses were paid. A study of lottery efficiency by International Gaming and Wagering Business magazine showed that overall it cost $0.3439 for each dollar raised for government programs by the lotteries. The efficiency of raising money ranged from New Jersey, where it cost $0.2020 cents, to South Dakota and Montana, where it cost over one dollar in expenses to raise the dollar for government programs via lotteries.

Criticisms

Criticisms of lotteries come from several sources. With information such as that in the preceding section, many have suggested that lotteries are an inefficient way to raise money for government. Lotteries are also open to the charge of being regressive taxes, albeit “voluntary” ones, as Thomas Jefferson suggested. The National Gambling Impact Study Commission reserved many of its harshest criticisms for state lotteries. It should be added that lottery organizations were not represented in the membership of the commission. The commission was strong in protesting against lottery advertising both for being misleading and for encouraging people to participate in irresponsible gambling. The commission also concluded that lotteries did not produce good jobs. Special criticism was reserved for convenience gambling involving lotteries, as the commission recommended that instant tickets be banned and that machine gaming outside of casinos – such as video lottery terminals at racetracks – be abolished.

Some also criticize lotteries as inappropriate enterprises that redistribute income by taking money from the poor and making millionaires, suggesting that some of these new millionaires are unprepared for their wealth and do not use it responsibly. This criticism is dealt with at length in H. Roy Kaplan’s Lottery Winners (1978), discussed in the Annotated Bibliography.

The drawing of lots probably constitutes the oldest form of gambling, and in modern times these games are the most prevalent form of gambling. Public opinion polls also show that the public approves of legalization of lotteries more than any other form of gambling.

History and Development

There is evidence that lottery games were played in ancient China, India, and Greece. The “drawing of lots” constitutes most of the references to “gambling” in the Holy Bible. The technical elements of gambling may not necessarily have been present, however, in all the biblical situations, as lots were used mostly for decision making.

Lotteries were part of Roman celebrations. They were used at Roman parties to present gifts to guests, much as door prizes are given at parties and events today. Lotteries were also found in the Middle Ages, as merchants used drawings to dispose of items that could not otherwise be sold.

The first lottery game based upon purchases of tickets and awards of money prizes was instituted in the Italian city-state of Florence in 1530. Word of its success spread quickly, as France had a lottery drawing in 1533. The English monarch authorized a lottery that began operations in 1569. The English lotteries were licensed by the crown, but they were operated by private interests. One of the first lotteries held was for the benefit of the struggling Virginia Colony in North America. The 1612 drawing was held in London. Lotteries were soon being conducted in Virginia and the other colonies, however. It cannot be known for certain when the first lottery occurred in North America, as Spanish royalty had also approved of lotteries and may have held drawings in their colonial possessions. And, of course, Native Americans had games which encompassed the attributes of lotteries. The first lottery game based upon purchases of tickets and awards of money prizes was instituted in the Italian city-state of Florence in 1530. Word of its success spread quickly, as France had a lottery drawing in 1533. The English monarch authorized a lottery that began operations in 1569. The English lotteries were licensed by the crown, but they were operated by private interests. One of the first lotteries held was for the benefit of the struggling Virginia Colony in North America. The 1612 drawing was held in London. Lotteries were soon being conducted in Virginia and the other colonies, however. It cannot be known for certain when the first lottery occurred in North America, as Spanish royalty had also approved of lotteries and may have held drawings in their colonial possessions. And, of course, Native Americans had games which encompassed the attributes of lotteries.

Lotteries were very popular throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in North America, and they were utilized both by governments and private parties. As in the Middle Ages, merchants used lotteries to empty shelves of undesired or very high priced goods. Individuals would do the same when they wished to sell estates, and no persons had sufficient capital to purchase large holdings. Institutions used lotteries to fund many building projects – for both public and private use. Canals, bridges, and roads were funded through lotteries, as banking institutions and bonding mechanisms were not yet developed in the colonies.

The reconstruction of Boston’s Faneuil Hall in 1762 was accomplished through the sale of lottery tickets. So, too, were construction projects for many colleges, including Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Dartmouth, Brown, and William and Mary. Colonial churches were not universally opposed to lotteries, as they also used ticket sales to build structures. Only the early Puritans and the Quakers voiced opposition.

Generally, governments did not use lotteries except for specific building projects. They did, however, institute laws to license as well as govern operations of lotteries; many lotteries were outside of government supervision. Most uses of lotteries had a noble or charitable purpose. Several entities, first as colonies and then as states used lotteries for the support of military activities during both the French and Indian Wars of the 1750s and the Revolutionary War two decades later. The Continental Congress authorized four lotteries in support of George Washington’s troops.

As the new nation began and a new century opened, lotteries remained very popular. Thomas Jefferson, who had earlier (in 1810) indicated that he would never participate in a lottery “however laudable or desirable its object may be”, changed his outlook in 1826, as he was financially short and desperately needed money to manage his estate. He asked the Virginia legislature to allow him to operate a lottery. In his later years he had mellowed on the subject of lotteries, as he described the lottery as a “painless tax, paid only by the willing”.

Lotteries proliferated in the early decades of the nineteenth century. In 1832 there were 420 drawings in the United States. The price of all the tickets combined constituted 3 percent of the national income and exceeded by several times the federal government budget. Soon the lottery was on a downhill slide, however, as the reform movement led by Pres. Andrew Jackson coalesced opposition to the drawings. Loose regulations and controls had permitted many scandals to surround the games. In one case a bogus lottery sold $400,000 worth of tickets but awarded no prizes. A Maine lottery director was discovered to have personally kept $10 million as expenses for a lottery that sold $16 million of tickets. In 1833 states started passing laws abolishing lotteries. First, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New York prohibited the games, then all other states followed suit. As new states wrote their constitutions, the prohibitions were locked into basic laws. By the start of the Civil War only the border states of Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky allowed lotteries. At the end of the war there were no lotteries.

The Civil War brought devastation to the American South, and several states looked toward lotteries for help. Most of the attempts to raise money with this kind of gambling were short-lived, however. Only the notorious Louisiana Lottery persisted into the 1890s. The Louisiana Lottery was conducted by private parties under a license from the state. Considerable corruption and bribery generated by the operation led the citizens of the state to ban the lottery in a public referendum. Legal lotteries ceased to exist in the United States until New Hampshire authorized a state-run sweepstakes in 1963.

Although legal lotteries remained dormant for nearly seven decades, illegal operations flourished in many parts of the country. In the nineteenth century, side lotteries had developed, as private syndicates, for a few pennies, would allow a person to “insure” that a number would not be selected. This game became known as policy, and was the forerunner of the numbers game. By the early decades of the twentieth century, the numbers game was well entrenched as an organized crime enterprise.

Lotteries returned to the legal scene with the passage of the New Hampshire Sweepstakes Law in 1963. Ticket sales began days after local communities approved their sale. Each cost three dollars, and buyers registered their names and addresses. The new lottery was based upon results of a horse race. First, forty-eight winning tickets were picked and each assigned to a horse in a special race. Depending on how the horse ran, the winners received from $200 to $100,000. The results were not an overwhelming success, but they generated substantial interest in the lottery idea. In 1967 New York State instituted a state-run lottery with monthly drawings. Tickets were purchased at banks where the buyers registered their names as in New Hampshire. In 1969 New Jersey followed. New Jersey was the first state to achieve desired levels of sales, as they used a weekly game and attracted customers with mass-marketing techniques. New Jersey also appealed to customers by selling tickets for fifty cents each, and players did not have to declare their names. New Jersey also utilized computers to track sales.

New Hampshire, New York, and New Jersey were not the first North American or Caribbean jurisdictions to have lotteries in the twentieth century. Mexico had established a game in the 1770s while it was still governed from Madrid, and the game persisted as the country gained its independence. Puerto Rico started its lottery in 1932. Canada, however, was influenced by the activity in the United States, as the national Parliament approved lottery schemes under provincial control in 1969. The first provincial lotteries appeared in Quebec in 1970. The spread of lotteries was quite rapid after the 1970s. All Canadian provinces as well as the Yukon Territory and Northwest Territories instituted games, as did most of the states. By the end of the century lotteries were in thirty-seven states plus the District of Columbia. Politically, the lotteries have commanded public favor, as many states adopted lotteries through popular referenda votes that amended state constitutions. Of all the states only two, North Dakota and Alabama, have ever rejected lottery propositions.

Lottery revenues constitute over one-third of all the gambling revenues in North America. State and provincial governments have come to rely on the revenue, although in most cases it constitutes 3 percent or less of the budgets of the jurisdiction. The revenues fluctuate from year to year, but over the past several decades they have provided a constant steady flow of money to public treasuries. The certainty of that steady flow is dependent upon governments’ adjusting to changing market desires of players and to advertising efforts. Game formats have changed considerably since New Hampshire first used its horse-race sweepstakes drawings. When one state offered an innovation – as New Jersey did in 1969 – other lottery states and provinces often followed with imitations. In 1974 Massachusetts began an instant lottery game using a scratch-off ticket that is preprogrammed to be a winner or loser. In 1975 New Jersey started a numbers game with the specific goal of competing with (and hopefully destroying) the prevalent illegal numbers game. New Jersey also installed an online system for tracking numbers at the same time.

Massachusetts tried a lotto game temporarily in 1977; then Ontario instituted the first permanent lotto game in 1978. Players choose six numbers from one to forty, and if no player has all six winning numbers, part of the money played is carried over into a future drawing with new sales of fresh tickets and a new drawing of winning numbers. Massachusetts allowed telephone accounts for lottery sales in 1980. South Dakota introduced the video lottery in 1989 with state-owned gambling machines that operate not unlike slot machines – albeit winning players receive tickets they must redeem for cash. The state of Oregon introduced its sports lottery also in 1989. Players pick four teams on a parlay card and if all the teams win, they receive a prize awarded on a pari-mutuel basis. In the 1970s Delaware had tried a sports lottery based upon individual National Football League games, but dropped the experiment after it suffered significant financial losses. Sports lotteries did not spread to other states, as Congress passed a law banning sports betting in all but Nevada, Oregon, Delaware, and Montana. Canadian provinces have sports lotteries.

With the beginnings of lotto games, lottery operations all went online; all the gaming sales outlets in the jurisdiction were linked together with a computer network. The next stage of lottery gaming could consist of games linked to individual home computers. Several European jurisdictions and Australian states offer these games. The Coeur d’Alene Indian tribe of Idaho had such a game for a brief time. Political opposition to Internet gambling, as well as attempts to enforce existing laws against transmitting bets over state lines, have precluded lotteries from venturing more into Internet gambling.

Several small states have banded together in order to offer bigger prizes and thereby compete with the bigger states. The first multistate lottery began in 1985 and involved New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont. This was but a precursor of the Powerball game that started in the mid-1990s with the participation of twenty-one state lotteries. Another latter-day innovation for lotteries has been the use of instant ticket vending machines. It is estimated that there are 30,000 of the machines in operation in thirty states today.

The post office said if he wanted delivery service he had to give a name to the town. And so in 1970, Laughlin, Nevada, was added to the map. Don Laughlin had moved to the “community”, if it could be called that, four years before. He had been looking for a place to put a gambling hall, and he found a patch of land at the extreme south end of the state, near Davis Dam and across the Colorado River from a small town called Bullhead City, Arizona. Laughlin had run a small casino called the 101 Club in North Las Vegas for five years before he sold it in 1964 for $165,000. That was his stake as he entered the barren desert 100 miles south of Las Vegas. The post office said if he wanted delivery service he had to give a name to the town. And so in 1970, Laughlin, Nevada, was added to the map. Don Laughlin had moved to the “community”, if it could be called that, four years before. He had been looking for a place to put a gambling hall, and he found a patch of land at the extreme south end of the state, near Davis Dam and across the Colorado River from a small town called Bullhead City, Arizona. Laughlin had run a small casino called the 101 Club in North Las Vegas for five years before he sold it in 1964 for $165,000. That was his stake as he entered the barren desert 100 miles south of Las Vegas.

Don Laughlin did not come to Nevada as an amateur in the gambling business. He was born and raised in Owatonna, Minnesota, in the 1930s and 1940s. There he saw gambling machines and other paraphernalia and instantly found them fascinating. As a teenager just beginning high school, he somehow ordered a slot machine from a mail-order catalog and was able to place it in a local club. Using profits from the machine, he bought more machines, and soon he ran a route of machines, punchboards, and pull tabs. Of course, all of this was illegal. He was forced to leave school because of his activity, but he did not mind, as he was making very good money for the time. It was not until 1952, following the work of the Kefauver Committee, that Minnesota cracked down on this illegal activity. With the passage of the Gambling Devices Act of 1951 (the Johnson Act), manufacturers could not easily ship gambling machines into the state. Laughlin knew there had to be better places to ply his trade. He vacationed in Las Vegas and quickly repeated the words of Brigham Young, “This is the place”. In his twenties he worked in casinos and bars and then purchased his own beer and wine house. He added slot machines. His modest success allowed him to have funds to buy the 101 Club.

In Laughlin, Don Laughlin acquired an eight-room motel, which became the basis for expansion. He called his resort the Riverside. By 1972 it had forty-eight rooms and a casino. Eventually the Riverside grew to 1,400 rooms and a recreational vehicle (RV) park with 800 spaces.

Today the Riverside is but one of ten casino hotels in a community having 11,000 rooms. Certainly Laughlin was gambling’s boomtown of the 1980s as Harrah’s, the Hilton, Circus Circus, Ramada (Tropicana), and the Golden Nugget all built there. In the 1990s business fell off as Native American casinos in both California and Arizona picked off customers on their way to the river resort. Laughlin has also been hurt by large casinos in Las Vegas and by the fact that commercial air travel to the town is very limited. The essential market for the town is drive-in traffic from southern California and the Phoenix area as well as a steady stream of senior citizens from all over the United States and Canada. Laughlin features many RV parks near all of its resorts as well as the most inexpensive hotel rooms in a gambling resort in North America. Don Laughlin continues to be a booster for the gambling town, seeking to have events that will attract both younger and older patrons. Country music artists and motorcycle rallies are always part of the fare.

<

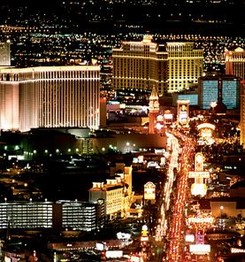

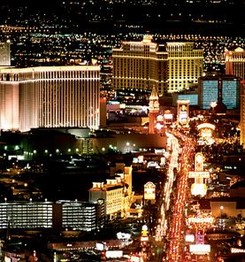

From its earliest days, Las Vegas catered to travelers. Its springs watered not only the crops of local Indians but also the meadows (las vegas is Spanish for “the meadows”) that in the 1830s supported an oasis for whites traveling the Old Spanish Trail between New Mexico and southern California. In 1855, Mormons built a fort and mission there, which also acted as a hostel for those plying the route between Utah and the church’s colony in San Bernardino, California. Following the Civil War, several farm-ranches occupied the valley until 1905, when Sen. William Clark, principal owner of the newly created San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, purchased Helen Stewart’s ranch for $55,000. On this tract he platted his Las Vegas Townsite, a division town complete with yards, roundhouse, and repair shops. In addition, he used the ranch’s water rights to supply his town and the thirsty boilers of his steam locomotives. From its earliest days, Las Vegas catered to travelers. Its springs watered not only the crops of local Indians but also the meadows (las vegas is Spanish for “the meadows”) that in the 1830s supported an oasis for whites traveling the Old Spanish Trail between New Mexico and southern California. In 1855, Mormons built a fort and mission there, which also acted as a hostel for those plying the route between Utah and the church’s colony in San Bernardino, California. Following the Civil War, several farm-ranches occupied the valley until 1905, when Sen. William Clark, principal owner of the newly created San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, purchased Helen Stewart’s ranch for $55,000. On this tract he platted his Las Vegas Townsite, a division town complete with yards, roundhouse, and repair shops. In addition, he used the ranch’s water rights to supply his town and the thirsty boilers of his steam locomotives.

The little whistlestop struggled along into the 1930s, experimenting with commercial agriculture and other small industries to supplement its transportation economy, but without success. The first seeds of change came in 1928 when Congress appropriated funds for building Hoover Dam. Construction began in 1931, the same year that the state legislature re-legalized gambling and liberalized the waiting period for divorce to six weeks. The dam was an immediate tourist attraction, drawing 300,000 tourists a year. But even with these visitors and the 5,000-plus men who toiled on the project, gambling remained a minor part of Las Vegas’s economy. When construction ended in 1936 and the dam workers left, the city experienced a mild recession. By decade’s end, the town’s population numbered only 8,400.

The real trigger for casino gambling was World War II. The sprawling Desert Warfare Center south of Nevada’s boundary with Arizona and California, along with Twentynine Palms, Camp Pendleton, Las Vegas’s own army gunnery school, and other military bases, provided thousands of weekend visitors who patronized the casinos. Supplementing these groups were thousands more defense workers from nearby Basic Magnesium and from southern California’s defense plants.

This sudden surge in business sparked a furious casino boom, helped by reform mayor Fletcher Bowron’s campaign to drive professional gamblers out of Los Angeles. Beginning in 1938, they began fleeing to Las Vegas, bringing their valuable expertise with them. Former vice officer and gambler Guy McAfee opened the Pioneer Club downtown and the Pair-O-Dice on the Los Angeles Highway (later the Strip) before unveiling his classy Golden Nugget (with partners) in 1946. Las Vegas also drew the attention of organized crime figures. Bugsy Siegel and associate Moe Sedway came to town in 1941 at the behest of eastern gangsters who were anxious to capture control of local race wires, the telephone linking system for taking bets on horse races.

Fremont Street grew, as older establishments bordering its sidewalks yielded to modern-looking successors. But a more significant trend in the 1940s was the Strip’s development. The first major resort was the El Rancho Vegas, which revolutionized casino gambling. The brainchild of Thomas Hull, the hotel exemplified the formula he developed for the Strip’s success. In 1940, he amazed everyone by rejecting a downtown location for more spacious county lands in the desert just south of the city. In the old West, gambling had always been confined to riverboats and small hotels near some railroad or stagecoach station. With his El Rancho Vegas Hotel, Hull liberated gambling from its historic confines and placed it in a spacious resort hotel, complete with a pool, lush lawns and gardens, a showroom, an arcade of stores, and most important, parking for 400 cars. It was Hull, the southern Californian, who recognized that the highway (with its cars, trucks, and buses) rather than the railroad was the transportation wave of the future and that in the age of electric power, a downtown location was no longer superior to a suburban one.

For the most part, the El Rancho’s successors in the 1940s, such as the Hotel Last Frontier, the Flamingo, and Thunderbird, followed Hull’s model although with a larger and more plush format. The Flamingo, built by Bugsy Siegel and the Hollywood Reporter’s Billy Wilkerson, freed Las Vegas from the traditional Western motif slavishly followed by resorts such as the El Rancho and El Cortez downtown. With its Miami Beach–Monte Carlo ambience, the Flamingo opened a new world of thematic options for future resorts such as Caesars Palace and the Mirage.

The Strip assumed its familiar shape in the 1950s with the addition of eleven new resorts. Contributing to this growth was the liberalization of the nation’s tax laws, which now permitted substantial deductions for business travel for professional improvement or the exhibition of goods. Anxious to fill their hotel rooms during the week, Las Vegas and Clark County officials formed a convention and visitors board in 1955 and built the Las Vegas Convention Center behind the Riviera Hotel on land donated by Horseshoe Club owner Joe W. Brown. Beginning in 1959, this new meeting hall, with its proximity to the Strip, tended to divert delegates away from Fremont Street. The construction of a new airport in 1947–1948 south of what became the Tropicana Hotel and its enlargement into a modern jetport in 1962–1963 only intensified the trend away from downtown. Construction of Interstate 15 in the 1960s along the resort corridor’s west side, with five strategic exits compared to just one for downtown, contributed further to the flow of traffic to the emerging Strip.

In the 1960s, funding of the Southern Nevada Water project by Pres. Lyndon Johnson awarded the metropolitan area enough Lake Mead water to support a city of 2 million people, a vital prerequisite for the city’s future growth. In addition, passage of Gov. Paul Laxalt’s corporate gaming proposal in 1969 promoted the city’s future development by ending the traditional requirement that every stockholder be investigated. The new law limiting the licensing procedure to only “key executives” permitted the entry of Hilton, Hyatt, MGM, and other corporate giants into the state. Only these entities, with their access to large pools of capital, could afford the billions necessary to build the megaresorts that characterize Las Vegas today.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a number of new technological advances and social trends reinforced the city’s growth, leading to construction of spectacular newcomers such as Caesars Palace. Chief among these trends was the so-called middle-classification of the United States. In the postwar era, with more Americans graduating from high school and even college and with the postindustrial economy creating more high-paying white-collar jobs, both disposable and discretionary income – crucial to the budgets of gamblers and vacationers—soared. Moreover, income in California increased by more than the national average. Even blue-collar workers enjoyed substantial income gains. Las Vegas also benefited from the growth in automation and generous union contracts that gave workers more vacation and holiday time for leisure pursuits. In addition, the introduction of the credit card by Diner’s Club in 1950 and arrival of the first commercial passenger jets in 1957 not only expanded Las Vegas’s market zone to the East Coast, Europe, and Asia, but also eliminated the need to travel with large amounts of cash. These innovations, along with automated teller machines, debit card, and computers, all made long-distance travel easier, liberating Las Vegas from its dependence upon southern California.

Following a brief recession occasioned by the debut of Atlantic City, which temporarily siphoned off some of Las Vegas’s East Coast market, the city rebounded in the 1980s and 1990s. In what has been Las Vegas’s most spectacular round of expansion, a new generation of casino executives epitomized by Steve Wynn joined an older group led by Kirk Kerkorian to transform the casino city into a major resort destination. Several factors contributed to the metropolitan area’s mercurial growth. First was the construction of several lavish new hotels. The $630 million Mirage set a record for cost when it opened in 1989 and instantly became the state’s leading tourist attraction, usurping the title held by Hoover Dam for over five decades. Quickly eclipsing the Mirage’s price tag was Kirk Kerkorian’s 1993 MGM Grand Hotel and Theme Park, which at nearly $1 billion was the most expensive hotel ever built. Steve Wynn, however, upped the ante almost immediately by imploding the Dunes Hotel and replacing it with the $1.6 billion Bellagio. At the same time, former COMDEX Convention mogul Sheldon Adelson took over the venerable Sands Hotel and demolished it to make way for the Venetian, a $1.5 billion Renaissance successor. These and other city-themed resorts such as New York–New York and Hilton’s Paris combined with Circus Circus’s upscaled properties embodied by Luxor and Mandalay Bay to transform the Strip into an even greater tourist Mecca.

The second factor went beyond the money, the new restaurants, and bigger and grander casinos. Wynn helped pioneer a new approach to luring additional visitors to Las Vegas when he introduced the concept of offering special attractions both inside and outside his casino. The Mirage initiated the idea in 1989 with its erupting volcano, white tigers, and bottlenosed dolphins; Wynn continued the trend with his outdoor pirate battle at Treasure Island and Bellagio’s “dancing fountains”. MGM’s theme park, Paris’s Eiffel Tower, the Stratosphere, and the Las Vegas Hilton’s Star Trek Experience only added to the fare.

A number of other themes have also characterized Las Vegas’s efforts to broaden its market, among which has been an appeal to families. This trend actually dates from the 1950s when the Hacienda’s Warren and Judy Bayley pursued the niche by offering guests multiple swimming pools and a quarter-midget go-cart track. In the 1970s, new Circus Circus proprietors William Bennett and William Pennington took their casino’s clown theme and applied it to families rather than to high rollers as the original owner had tried to do. They added a carnival midway of games, candy stands, and toy shops and later supplemented it with a domed, indoor amusement park packed with thrill rides. Circus Circus repeated this success in the 1990s with its Excalibur Hotel, a dazzling medieval castle priced to attract the low-end family market. But despite these and other efforts to soften Las Vegas’s image nationally, families have consistently represented no more than 8 percent of the town’s visitors.

A third factor was that in the 1980s and 1990s, Las Vegas gamers also acquired a substantial home market as the metropolitan area’s population skyrocketed from 273,000 in 1970 to more 1.3 million by century’s end. The first major neighborhood casinos catering primarily to locals came in the 1970s when Palace Station (1976) and Sam’s Town (1979) began operations. Reinforcing this market was the development of a new sector in the Las Vegas economy, the retirement industry. Following the deaths of gaming figures Del Webb (1973) and Howard Hughes (1976), their two companies joined forces to build what eventually became Sun City Summerlin. Since Hughes had purchased most of the outlying lands west of the city in the 1940s and Del Webb possessed the construction expertise to build homes, the companies formed a partnership and began work on Sun City in the mid-1980s. This project, along with its satellite communities, will ultimately contain more than 30,000 homes. Already, thousands of retirees have moved to Sun City and other small projects around the city. Las Vegas is the only place where they can not only “go to the malls” and engage in the traditional forms of leisure offered by Miami and Phoenix but also gamble on horses, sports, and cards.

In addition to these new flourishes, the casinos have pushed the addition of high-end retailing centers, such as the Forum Shops at Caesars Palace and its clones at the Venetian and elsewhere. The results have been nothing less than dramatic. As the twentieth-first century dawned, more spectacular resorts, world-class shopping, and special attractions had combined with the growing national and global popularity of casino gambling to make Las Vegas the leading tourist center in the United States—surpassing its nearest rival, Orlando.

In 1902 Meyer Lansky was born Meyer Suchowljansky in Grodno, a small city in a region that has been – at different times – in Russia, Poland, and Germany. The mostly Jewish community was confronted by pogroms conducted by Czarist Russia. Meyer’s father fled to the United States in 1909. When Meyer was about ten years old, he came to the United States with the rest of his family. They all settled in a low-rent neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. From these humble beginnings in the tenements, Meyer Lansky rose to become the “godfather” of a national crime syndicate, a principal in an organization called “Murder, Incorporated”, and the person recognized as the financial director of Mob activity in the Western Hemisphere.

Much of the financial activity conducted by Lansky concerned money used for the establishment of casinos – both legal and illegal – and also money taken out of the profits of these casinos. Meyer and his brother, Jake, who became involved in many of Meyer’s activities, learned about crime on the streets of Brooklyn. Lansky was also an excellent student with a mind finely tuned for mathematical skills. He took a liking to the gambling rackets he observed on his neighborhood streets, because the games and scams conducted by various sharps and gangsters had a certain mathematical quality at their core. He also learned about the psychology of gambling and how the activity could prey upon the gullibility of players. Lansky also learned that street life had its violent side. While still a teenager, he intervened to stop another boy he had never met from shooting a fellow craps player. The aggressive boy was Benjamin Siegel. There on the streets, in the middle of what could have been a violent episode that could have ended what became a violent career anyway, Lansky and Siegel (later to be known as “Bugsy”) became very close friends. They became partners in crime until the end – that is, to Siegel’s end. Lansky was able to control Siegel’s temper as no one else could, and he was also able to direct Siegel’s penchant for violence. The two shared a similar background on the streets. When Prohibition began in 1921, they were prepared to be business partners.

Together Lansky and Siegel operated bootlegging activities. Bootlegging also brought Lansky into contact with Charlie “Lucky” Luciano. As their imbibing customers also craved gambling, their businesses were expanded. Liquor, betting, and wagering went together. With regard to gambling, Lansky was different from other mobsters running gambling joints. The others had proclivities to cheat customers, but Lansky knew the nature of the games. You did not have to cheat to make money. The odds favored the house, and all the operator needed was to have a certain volume of activity and to make sure that players were not cheating the house. Lansky could handle the numbers of customers he needed, and the numbers involved in determining the odds of each game. His mind was a calculator that allowed him to play it straight with the customers – and with his partners. But his operations also had rivals, and he cooperated with Luciano, Siegel, and others in consolidating control over their business enterprises by using violence.

When Prohibition ended on 5 December 1933, gambling became the major business interest for Lansky and many of his associates. Lansky became involved with gambling facilities in Saratoga Springs, New York; New York City; New Orleans; Omaha; and Miami. He also formed alliances with operations in Arkansas and Texas. In 1938, Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista begged Lansky to come to the island and establish some honesty in their gambling casinos. The dealers were cheating the customers, and they were also robbing the dictator blind. He wanted his share. Lansky agreed to give him $3 million plus 50 percent of the profits the casino made. True to his word, Lansky cleaned up the operations. Later he took his skills for running an “honest” game for illicit operators to Haiti, the Bahamas, and London’s Colony Club.

Perhaps Meyer Lansky’s greatest legacy in gaming was found in Las Vegas. There he established the Mob’s reputation for running honest games – albeit on behalf of mobsters. Lansky became a silent partner in the El Cortez in 1945. Soon his syndicate sold the property for a profit (they demonstrated it could make a profit), and they reinvested the money in the construction of the Flamingo Hotel and Casino in the Las Vegas Strip, six miles from the established casino area in downtown Las Vegas on Fremont Street. Bugsy Siegel was given the primary responsibilities for finishing the project. Siegel completed the job on time but not on budget. When the Flamingo opened in December 1946, it began to lose money. Lansky and his partners felt that Siegel had siphoned off much of the construction overruns as well as the operating revenues and put them into his own pockets – or into Swiss bank accounts. In June 1947 Siegel was murdered (by person or persons unknown) in the Beverly Hills apartment of his girlfriend. Soon afterwards the Flamingo was returning good profits under the operating hands of other Lansky associates.

Lansky’s presence in Las Vegas persisted through the 1960s, as he was a silent partner in many gambling houses. It was said that he developed and perfected the art of skimming in order to get his share of the profits into his own pockets. A typical skimming device was to give large amounts of credit to players on gambling junkets. The players would then repay their loans to Lansky’s associates, and not the casino, which would write them off as “bad debts”. It was alleged that Meyer Lansky skimmed $36 million from the Flamingo over an eight-year period. He was also alleged to have taken portions of the profits from the Sands, Fremont, Horseshoe, Desert Inn, and Stardust through similar skimming scams. Lansky also availed himself of large sums of money by taking a finder’s fee when the Flamingo Casino Hotel was sold to Kirk Kerkorian in 1968.

In 1970 Lansky started an abortive campaign to legalize casinos in Miami Beach, where he had a residence. The year was not a good one for Lansky, as he was charged with tax evasion in federal court. He escaped prosecution by fleeing to Israel. There he sought citizenship under the Law of Return, which offered asylum to any person with a Jewish mother. As a result of considerable international as well as domestic pressure, he was denied Israeli citizenship and was exiled from Israel in November 1972. Back in the United States, he had to face tax charges and skimming charges, as well as contempt of court charges for fleeing prosecution. He dodged these charges at first because the court recognized he was in ailing health. Then in 1974, after he had undergone heart surgery, his case was brought before federal judge Roger Foley in Las Vegas. Foley dismissed all charges. The U.S. Justice Department appealed the judge’s action but could not get it overturned.

Lansky was free and in the United States. But he was old and in ill health, and his family was in considerable turmoil. Although some sources suggested that he was a wealthy man – with resources between $100 and $300 million—he was not. His resources were depleted as he lived out his last years alone and with very few assets. He was estranged from his daughter, and one handicapped son died in abject poverty. Perhaps the longest reign of an American “godfather” ended with little notice when he died in 1983.

<

The Knapp Commission (officially known as the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Police Corruption and the City’s Anti-Corruption Procedures) consisted of five leading citizens of New York City. The commission was instituted by an executive order of Mayor John V. Lindsay on 21 May 1970. Lindsay appointed Whitman Knapp as chairman. Joseph Monserrat, Arnold Bauman (later replaced by John E. Sprizzo), Franklin A. Thomas, and Cyrus Vance (later secretary of state in the Carter administration) were commission members. The commission met for two years and issued its final report on 26 December 1972.

The creation of the commission was not driven by policy considerations of Mayor Lindsay. Quite to the contrary – city officials, as well as top police administrators, were said to be quite content to allow a persistence of on-street corruption of policy activity through bribery in exchange for having a police force that could basically ensure publicly acceptable levels of social control and criminal activity. Their priorities were often directed toward overlooking certain illegal activities by police if strict enforcement would negatively impact police morale.

Allegations of police corruption have dogged the police force of New York City since its creation in 1844. Investigations have been conducted on a periodic basis. A New York state senate committee (known as the Lexow Committee) looked at police extortion of houses of prostitution and gambling operations in 1894. In 1911 the city council appointed a committee led by Henry Curran to look into police involvement in the murder of a gambler in Times Square. The gambler had revealed to city newspapers a pattern of bribes that he had paid to the police. In 1932 the state legislature again sponsored an investigation under the leadership of Samuel Seabury. It examined cases of bribes paid to police by bootleggers and gamblers. In 1950 and 1951 the district attorney again held grand jury hearings into bribery tied to gambling. Harry Gross, the head of one of the largest gambling syndicates in the city, agreed to testify. Twenty-one policemen were indicted, but charges were withdrawn when Gross ceased to cooperate in the hearings.

In the mid-1960s, it could be expected that the issue would somehow resurface again. This time the catalyst for investigations was a policeman whose quest was to be an “honest cop”. His name was Frank Serpico. Serpico’s story was the subject of a popular book by Peter Maas (Maas 1973) and a widely acclaimed movie, Serpico, released in 1973, starring Al Pacino in the role of Frank Serpico. Shortly after joining the police force, Serpico became aware that officers were taking bribes from persons involved in numbers betting and illegal sports betting. Soon he discovered the depth of a network of bribes tied to protection given to various games. Operators of different kinds of games would pay different levels of bribes depending upon the volume of their activity and the public exposure given their activities. Open gambling games would require higher bribes. All the police of a precinct would participate in the police bribes, with varying shares given to uniformed officers, plainclothes officers, detectives, and higher administrators.

At first Serpico simply refused to accept his share of the bribe money. But as he could not escape personal involvement with the situation on a day-by-day basis, he confided his displeasure to higher police officials. Although he was very reluctant to name any fellow officers in his discussions, he was eager that an investigation follow so that the practices would cease. He found little satisfaction within the police hierarchy and instead was severely ostracized. Even contacts with the mayor’s office were futile. The highest politicians in the city were more concerned that police morale be high, as race riots were anticipated and general social “peace” in the streets was their priority. Serpico’s persistent actions led to internal proceedings that resulted in individual convictions of lower-level policemen. He saw little action at top levels where general reform had to start, although a higher-level investigation was initiated. In frustration and fear for his personal safety, Serpico and two supportive fellow officers decided to go on record and make their story public.

On 25 April 1972, the New York Times reported Frank Serpico’s story on the front page “above the fold”. The cat was out of the bag, and Mayor Lindsay could no longer hide behind bureaucratic values. He immediately appointed an interdepartmental committee to recommend action. The committee asked for public complaints that would back up the New York Times story. They received 375 complaints within a couple of weeks. They told the mayor that as regular city employees they did not have time to follow up with an investigation. They urged that the mayor create what became the Knapp Commission (Knapp Commission 1972, 35).

The city council approved a budget for the commission and also gave it subpoena power. Additional funds were received for the work through the U.S. Law Enforcement Assistance Administration. An investigating staff was formed, and several inquiries into illegal activity were made in the field. The commission also held two sets of hearings. Five days were spent with Frank Serpico and his fellow confidants. The commission also invited public complaints, and they received 1,325 in addition to those sent to the mayor’s earlier committee. In addition to the Knapp Commission’s report, their work led to the indictments of over fifty police officers. Over 100 were immediately transferred after the hearing began.

The commission spent considerable time discussing what is known as “the rotten apple theory”, specifically that corruption is not pervasive but rather the result of a few “rotten apples” that somehow get into every barrel. They rejected that supposition, as their report began with the words, “We found corruption to be widespread”. In one precinct they found that twenty-four of twenty-five plainclothes policemen were involved in receiving bribes from illegal gamblers. Although group norms motivated police to participate in networks of bribery, so did their realization that the enforcement of gambling laws was not taken seriously by the judicial system. The commission reported that between 1967 and 1970 there were 9,456 felony arrests for gambling offenses. These resulted in only 921 indictments and 61 convictions. Of these, only a very few received jail sentences, and the sentences were “nominal”.

Although the commission’s report dealt with a wide range of corrupting activities, a special focus was upon gambling and the bribes gamblers paid to the police in their part of the city. The activity was found in all parts of the city. Ghetto neighborhoods were especially susceptible to this police activity. One witness indicated: “You can’t work numbers in Harlem unless you pay. If you don’t pay, you go to jail. You go to jail on a frame if you don’t pay”.

The commission found that the “most obvious” result of the gambling corruption was that gambling was able to operate openly throughout the city. Although those with no moral opposition to gambling were not upset, they realized that the pattern of bribery in this area opened the police up to other corruption – looking the other way during drug activity, during certain Mob larcenies, and during other Mob activity. The commission saw a definite link between Mob organizations and gambling activity. The bribery pattern also taught the public that the police were not to be respected. This was especially harmful for children.

An additional danger to police corruption was that the police neglected their specific law enforcement duties as they concentrated on collecting their bribes and protecting gamblers. One remark from Serpico was telling. In effect, he said that all the crime in New York City could be ended if the police were not so busy seeking payoffs. The police responded to the commission by indicating that they were no longer concentrating on small gambling operatives but rather would focus on leaders in gambling operations. The commission felt that this might be admirable, but that it was not sufficient. They believed that “gambling is traditional and entrenched in many neighborhoods, and it has broad public support” (90). Such being their belief, they recommended that numbers, bookmaking, and other gambling should be legalized. Moreover, the regulation of such legalized gambling should be by civil agents and not by the police.

As the commission rejected the “rotten apple” theory, so did the Commission on the Review of the National Policy toward Gambling. They reported that a Pennsylvania Crime Commission that began its study in 1972 also found bribes from gamblers to be pervasive in Philadelphia, and the same was also found in other large cities.

<

|

Instant Games

Instant Games  The first lottery game based upon purchases of tickets and awards of money prizes was instituted in the Italian city-state of Florence in 1530. Word of its success spread quickly, as France had a lottery drawing in 1533. The English monarch authorized a lottery that began operations in 1569. The English lotteries were licensed by the crown, but they were operated by private interests. One of the first lotteries held was for the benefit of the struggling Virginia Colony in North America. The 1612 drawing was held in London. Lotteries were soon being conducted in Virginia and the other colonies, however. It cannot be known for certain when the first lottery occurred in North America, as Spanish royalty had also approved of lotteries and may have held drawings in their colonial possessions. And, of course, Native Americans had games which encompassed the attributes of lotteries.

The first lottery game based upon purchases of tickets and awards of money prizes was instituted in the Italian city-state of Florence in 1530. Word of its success spread quickly, as France had a lottery drawing in 1533. The English monarch authorized a lottery that began operations in 1569. The English lotteries were licensed by the crown, but they were operated by private interests. One of the first lotteries held was for the benefit of the struggling Virginia Colony in North America. The 1612 drawing was held in London. Lotteries were soon being conducted in Virginia and the other colonies, however. It cannot be known for certain when the first lottery occurred in North America, as Spanish royalty had also approved of lotteries and may have held drawings in their colonial possessions. And, of course, Native Americans had games which encompassed the attributes of lotteries. The post office said if he wanted delivery service he had to give a name to the town. And so in 1970, Laughlin, Nevada, was added to the map. Don Laughlin had moved to the “community”, if it could be called that, four years before. He had been looking for a place to put a gambling hall, and he found a patch of land at the extreme south end of the state, near Davis Dam and across the Colorado River from a small town called Bullhead City, Arizona. Laughlin had run a small casino called the 101 Club in North Las Vegas for five years before he sold it in 1964 for $165,000. That was his stake as he entered the barren desert 100 miles south of Las Vegas.

The post office said if he wanted delivery service he had to give a name to the town. And so in 1970, Laughlin, Nevada, was added to the map. Don Laughlin had moved to the “community”, if it could be called that, four years before. He had been looking for a place to put a gambling hall, and he found a patch of land at the extreme south end of the state, near Davis Dam and across the Colorado River from a small town called Bullhead City, Arizona. Laughlin had run a small casino called the 101 Club in North Las Vegas for five years before he sold it in 1964 for $165,000. That was his stake as he entered the barren desert 100 miles south of Las Vegas. From its earliest days, Las Vegas catered to travelers. Its springs watered not only the crops of local Indians but also the meadows (las vegas is Spanish for “the meadows”) that in the 1830s supported an oasis for whites traveling the Old Spanish Trail between New Mexico and southern California. In 1855, Mormons built a fort and mission there, which also acted as a hostel for those plying the route between Utah and the church’s colony in San Bernardino, California. Following the Civil War, several farm-ranches occupied the valley until 1905, when Sen. William Clark, principal owner of the newly created San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, purchased Helen Stewart’s ranch for $55,000. On this tract he platted his Las Vegas Townsite, a division town complete with yards, roundhouse, and repair shops. In addition, he used the ranch’s water rights to supply his town and the thirsty boilers of his steam locomotives.

From its earliest days, Las Vegas catered to travelers. Its springs watered not only the crops of local Indians but also the meadows (las vegas is Spanish for “the meadows”) that in the 1830s supported an oasis for whites traveling the Old Spanish Trail between New Mexico and southern California. In 1855, Mormons built a fort and mission there, which also acted as a hostel for those plying the route between Utah and the church’s colony in San Bernardino, California. Following the Civil War, several farm-ranches occupied the valley until 1905, when Sen. William Clark, principal owner of the newly created San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, purchased Helen Stewart’s ranch for $55,000. On this tract he platted his Las Vegas Townsite, a division town complete with yards, roundhouse, and repair shops. In addition, he used the ranch’s water rights to supply his town and the thirsty boilers of his steam locomotives.