Archive for August, 2010

Boxing is one of the few sporting contests bet upon in which judges of performance may determine the results. The Nevada Gaming Commission does not otherwise permit bets on noncontests in which victory is not determined in some arena or field of action. Although sports books in England often list political election contests (even election contests in the United States), this is not permitted in Nevada casinos and sportsbooks. Las Vegas bettors are not allowed to wager on Academy Award winners, winners of contests such as the Miss America pageant, or Time magazine’s Person of the Year. A decade ago a famous television series ended its run with a revelation about who shot the star of the series (“Who Shot J. R.”). One casino put odds up on the list of television characters that might have done the terrible deed, but the odds were listed only in jest – or as a publicity stunt. No bets were taken.

Five years ago, however, the Palace Station casino did post odds and took bets at the beginning of a baseball season on just who would be named the most valuable player in each league. One bettor, Howard Schwartz, who just happens to run the Gambler’s Book Club in downtown Las Vegas – the largest gambling specialty bookstore in the world – decided he liked the twenty-five to one odds on Andre Dawson, a player with the Chicago Cubs. Schwartz wagered a modest ten dollars. When at the end of the season Dawson was named as the most valuable player; Schwartz retrieved his “winning” ticket and marched to the Palace Station. There he was cheerfully greeted and handed back ten dollars. He was told that the Nevada Gaming Commission had heard about the contest (it was advertised in the local newspapers); the commission had determined that the contest violated gaming rules, and it ordered the casino to stop the contest – to close it down. It was, of course, a stupid move on the part of the commission. They could have warned the casino never to do it again and fined it a sufficient amount of money to assure it they would never do it again and that others similarly inclined to have such contests would never do it again. Had they known the names of all persons who entered the contests, they could have returned all the entry money. But such names were not known, as bets (unless over $10,000 in cash) are made anonymously. Instead, they voided bets already taken. Schwartz was, to say the least, irate. Schwartz had a bona fide bet. He had put his money at risk. He had won. When told he could have his money back, he inquired if the casino had a plan to return money to all players including losers – including losers who quite naturally would not come to the casino expecting to cash in their tickets. They had no plan outside of some minimal signage. All the casinos were put on notice not to be put into such a position in the future, as Schwartz used his critically central location among serious bettors – his bookstore, as well as all the talk radio shows of Las Vegas – to inform the public that one casino would not pay off its winners. Of course, the Palace Station would have liked to pay off the winning ticket, but the gaming commission told it that it could not do so. Considerable public relations damage was done to the casino and all sports books in Las Vegas over the incident, but the point was made clear – it must be a legitimate sporting event determined on the field of play, or no bets can be taken.

In futures contests, the sportsbook or bookie offers odds on future results of contests – such as who will win next year’s Superbowl, World Series, the Stanley Cup for professional hockey, the NBA basketball championship, or the National Collegiate Athletic Association basketball championship playoffs. Most of these odds are offered as inducements for players to put a wager on their favorite or home team. The futures betting produces little serious wagering action.

In hockey contests, both goals and odds are used in the betting. In some cases there is a split line, with one team receiving 1.5 goals and the other team giving up 2 goals. Such a bet will be started at even odds. The house would be guaranteed a win of half the money bet if the game ended on the whole goal total – the plus-2 bettor would have his or her money returned, and the minus 1.5-bettor would lose his or her wager.

Most hockey betting does not use the split line approach. Rather an advantage of 1.5, 2.5, or 3.5 goals (or more in very rare cases) is assigned to one team, and on top of this there is a money line – usually set as a forty-cents line.

Parlay bets are figured the same way as in baseball. The hockey games also offer over and under bets on total goals scored.

Baseball is bet on an odds basis. For instance, a bet on a game between the Detroit Tigers and the Chicago White Sox may be listed as Tigers plus 110 and White Sox minus 120. This means that the person making the wager who bets on Detroit puts up $10 and wins $11 (collects $21) if Detroit is victorious. One betting on Chicago wagers $12 for the chance to win $10 (and collect $22). This “dime” line (so called in recognition that there would be a dime difference if bets were expressed as single dollar amounts rather than in terms of 100) produces the theoretical win of $10 per $220 wagered or 4.55 percent. As the bet odds increase, more money is bet, but the house edge remains at $10, hence the percentage edge falls. If the favored team demands a $200 wager to win $100, and the underdog a $100 bet to win $190, the house theoretically wins $10 on action of $590 (both player and house money), for a win of only 1.7%. For this reason casinos will abandon the dime line and move to fifteen-cents or twenty-cents lines on longer odds games. Hence, a bet may read Detroit plus 150, Chicago minus 170. Baseball is bet on an odds basis. For instance, a bet on a game between the Detroit Tigers and the Chicago White Sox may be listed as Tigers plus 110 and White Sox minus 120. This means that the person making the wager who bets on Detroit puts up $10 and wins $11 (collects $21) if Detroit is victorious. One betting on Chicago wagers $12 for the chance to win $10 (and collect $22). This “dime” line (so called in recognition that there would be a dime difference if bets were expressed as single dollar amounts rather than in terms of 100) produces the theoretical win of $10 per $220 wagered or 4.55 percent. As the bet odds increase, more money is bet, but the house edge remains at $10, hence the percentage edge falls. If the favored team demands a $200 wager to win $100, and the underdog a $100 bet to win $190, the house theoretically wins $10 on action of $590 (both player and house money), for a win of only 1.7%. For this reason casinos will abandon the dime line and move to fifteen-cents or twenty-cents lines on longer odds games. Hence, a bet may read Detroit plus 150, Chicago minus 170.

It is rare for the game to have a run differential – that is, a point spread, – but if the casino feels such is necessary, it awards 1.5 runs or more to one side, and then keeps the odds line (dime, twenty cents, etc.) the same.

Most baseball bets are made with pitchers for both teams listed on the betting proposition. The pitchers are usually listed a few days before a game. If by circumstances, a pitcher is withdrawn, and the pitcher listed was part of the bet, there is no action and all money is returned. For the bet to be effective, the listed pitchers must each make at least one pitch in the game as a starter.

Bettors are also able to bet on total runs, usually with a plus 110 and minus 120 edge. If the total runs are expressed in whole numbers, and the number is the actual game result, the bets are returned. Extra innings do not affect bet results.

Parlay bets are figured on the basis of the lines offered, with payoffs of each game multiplied.

Basketball betting for both professional and college games follows the general structure of football betting, with straight bets utilizing a point spread and with bets on total scores also being popular. Parlay bets with and without cards are also wagered quite often. As margins of victory vary considerably and do not come together on specific numbers – such as three in football – the threat of middling is less for the sports book. Most sports books also offer teaser bets.

The general condition of basketball betting would seem to suggest that theoretical hold percentages would be more likely achieved than with football games; however, another factor makes this achievement more difficult. There are many more basketball games than football games, and the results of basketball games are much more dependent upon individual players. One player or two can dominate a team’s performance much more than in football – with the general exception of the quarterback. There is a need for greater information about players in order to more accurately predict the outcomes of games. Yet with the number of games all over the country, bettors may have more information than the sports books – information about players’ health, emotional disposition, disputes within teams with accuracy, distractions based upon player life circumstances (perhaps examination schedules and class performance for college players). The college basketball betting public is also the most sophisticated of those making sports wagers. The most sports betting scandals have hit the college basketball ranks. Professional gamblers sense that they can compromise players who can more easily affect the points of victory (shave points) in college basketball. Many major league professional players make $1 million or more per season and hence are not vulnerable to offers of money or other favors to shave points. It must be noted, however, that the sports books (and illegal bookies as well) will probably be very cooperative with authorities in exposing players or teams that may be willing to compromise their point spread lines, because as the line is compromised, the sports books not only lose customers who feel that games are not honest but also find it more difficult to balance their books, hence realizing their theoretical profit margins. Dishonest games hurt the bookies and sports book the most – in a financial sense, anyway.

Football

Football did not carry much interest among bettors until the National Football League gained television contracts and displayed its special kind of action for the public. A critical event was the climax of the championship playoffs of 1957, as the Baltimore Colts defeated the New York Giants in a sudden-death overtime game viewed by the largest television audience for a sports event up to the time. The game marked a critical point at which national interest in football exceeded interest in baseball, a game that did not translate well to the public over television, as it had too many breaks in action.

Football sports betting received an extra boost as a new professional league began operations in the 1960s and then merged with the National Football League, bringing teams and games to each major city in the United States.

The Point Spread

The growing interest in football was tied to betting on the games. Betting increased considerably among bookies when a handicap system of point spreads was developed. Prior to the use of point spreads for football wagering, the bookies only offered odds on winners and losers of games. As many games were predictable, odds became very long. Players realized that they had little chance to win with the underdog, but at the same time, the bookies did not want to accept bets of sure-thing favorite teams, and they were reluctant to accept the possibilities of an underdog winning with odds of twenty to one or more. Therefore, many games simply were not available for the betting public. There is a dispute over just who invented the point spread. A Chicago stock market adviser, Charles McNeil, was credited by some for inventing the spread in the 1930s; two other bookies, Ed Curd of Lexington, Kentucky, and Bill Hecht of Minneapolis, are also cited for creating the spread decades later.

Bookies and the few legal sports books in operation in the 1950s and 1960s loved the spread for football and certain other games, as it greatly reduced their risks. Bookies do not want risks. They are businesspeople who want stability in their investments. The essential feature of the point spread was a guaranteed profit for the bookies – if the books could be balanced. Points are set for games with the goal of having an equal (nearly equal) amount of money bet on either side.

The point spread is called the line. The point spread refers to the betting handicap or extra point given to those persons making wagers on the underdog in a contest. Those betting on the favorite to win must subtract points from their team before the contest begins. The point spread is used most often for bets on basketball or football games. As an example, the New York Giants may be a seven-point underdog against the Green Bay Packers. Thus the line is Green Bay minus seven. Those betting on Green Bay will lost their bets unless Green Bay wins by more than seven points. Those betting on the New York Giants will win unless the Giants lose by more than seven points. The bet is a tie (called a push) if Green Bay wins by exactly seven points (Thompson 1997).

In 1969 the New York Jets were double digit underdogs against the Baltimore Colts in the Superbowl football game. The point spread was as high as eighteen points. Yet New York, under the guiding leadership of quarterback Joe Namath, defeated the Colts sixteen to seven. Although some considered that the point setters failed miserably on that game, they did anything but fail at all. Money books were balanced, and the bookies won their transaction fees. Although players bet on one side of the line, they must put up $11 in order to win $10. This means that if the books are perfectly balanced, with $11,000 bet on one side, and $11,000 bet on another, the bookie pays back $21,000 to the winning bettor, and keeps $1,000 out of the $22,000 that has been bet – for a 4.55% advantage over the bettors.

In actuality, this theoretical advantage is seldom realized. Bettors do not line up evenly on either side of the point spread, and some bettors have knowledge about the games superior to that of the point setters, taking advantage of the spread numbers. The bookies often find that they have to adjust lines in order to get more even betting on each side. In certain cases, a line may move two or three points, resulting in a situation called “middling,” whereby bettors on both sides—early bettors on one side, later bettors on the other side – can be winners. This happened with betting on the Superbowl in 1989. The three-point line, with San Francisco favored over Cincinnati, was moved to five or more points, as the bettors clearly favored the San Francisco 49ers (they were not only a California team – that is, near Las Vegas – but also they had won the Superbowl twice in the previous seven years). The game finished with a four-point San Francisco victory. Early San Francisco bettors won; later Cincinnati bettors won. Many of the bettors won both ways. The bettor gets the point spread that is listed at the time the bet is made, unlike the pari-mutuel situation in which odds are based upon the cumulative bets of the players.

Then there is the case in which the point setters do what some might consider their “job” perfectly. In the 1997 Superbowl game between Green Bay and New England, the Green Bay Packers were favored by fourteen points. The point setters were on target; they were perfect. The Packers won with a fourteen-point margin. The bookies and legal sportsbooks won exactly 0 percent on the game. They had to give all the money bet back to the bettors. The bets were a tie, a “wash.” Because ties on point spreads are bad for the sports books, there is a tendency to use half points in spreads, although these are moved when betting behavior demands that the points be changed. Also, bookies realize that certain spreads will lead to ties more often than others will. More games end with a three-point victory than any other specific point margin. Moving points up or down around the three-point margin is also dangerous because of the “middling” factor.

The Structure of Football Bets

The standard bet on football results has a player wagering that a favored team will either win by so many points or, conversely, that an underdog team will either win or will not lose by more than a determined number of points. If a game is considered to be an even match, no points are given either way. Such an even-match bet, with no points either way, is called a “pick-’em” by bettors. If the point spread is expressed as a full number, and the favorite team wins by that many points (or an even match ends in a tie), the bet is considered a tie (or “wash”), and the money wagered is returned to the player. There is no bet.

There are many betting opportunities other than a straight-up bet on which team will win and whether it will win by so many points. A very popular bet made on professional football games and many college games as well is the over-under. Here the point setters indicate a score that is simply the total number of points scored in the game. Bettors wager $11 to win $10 that the total score of the game will be more or less than the set number. There are also teaser bets that may be used either with one game or usually with bets on several teams. The bettor is given extra points for a game in exchange for having the odds on the bet changed against him.

Parlay bets are combination bets whereby the bettor wagers that several games (with point spreads) will be won or lost. For instance, on a two-team parlay, a bettor wagering $10 will win $26 (for a payback of $36) if both picks are correct. At even odds, the player should receive 3 to 1 for such a bet, or a return of $40. This means that the house edge on the bet is theoretically 10% – again assuming that bets on all sides of the parlay action are even amounts of money. A three-team parlay pays 6 to 1, and the even odds of such a parlay would be 7 to 1. The theoretical edge in favor of the sports book would be 12.5%. There are two kinds of parlay bets: ones made based upon the point spreads of the moment, and others made on a card where the point spread is fixed until the game is played. The latter type of cards may have a theoretical edge as high as 25% or more. For a three-bet parlay, cards usually payoff at a 5 to 1 rate. Sometimes cards allow tie bets to be winners; other times they are figured as “no-bets”; some cards may treat ties as losers.

There is also a wide array of proposition bets that are usually reserved for special occasions. Bettors may wager on many situations for the Superbowl game each year. For instance, the bettor is allowed to wager on which team will win the coin toss, have the most passes completed, score first; on how the first score will be made (touchdown, field goal, etc.); on which player will score first, how many fumbles there will be in the game, which team will lead at halftime, and many other situations. In the 1986 Superbowl, a Las Vegas casino offered a wager on whether Chicago Bear William “the Refrigerator” Perry – a 300-plus-pound offensive lineman would score a touchdown in the game against New England. He had been used as a back on gimmick plays during the season. The betting started with odds at thirteen to one but quickly came down as the betting public wagered that Perry would score a touchdown. Late in the game, which had become a rout (Chicago won forty-six to ten), coach Mike Ditka called Perry’s number. He lined up in the backfield and was given the ball. He scored a Superbowl touchdown.

There are possibilities for odds betting for some football games, although the sports books put the players at a considerable disadvantage for any games where the point spread betting exceeds seven points. One can wager on the “sure thing” but only at considerable risk. For instance, on an even, no-points, “pick-’em” game, players betting either side advance $11 in order to win $10. With a three-point spread, those wagering on the favorite bet $15 to win $10, and those wagering on the underdog wager $10 to win $13. For a 7.5 point game, those betting on the favorite might be asked to wager $40 to win $10, while those betting on the underdog would wager $10 to win $30. The theoretical house edge thereby moves from 4.55 percent for the even game, to 8 percent for the three-point spread game, to 20 percent for the 7.5-point game.

The biggest bet on a football game was made by maverick casino owner Bob Stupak, the owner of Vegas World and the creator of and an initial investor in the Stratosphere Tower. In 1995 he bet more than $1 million on a Superbowl game. He wagered $1,100,000 to win $1,000,000. And he won. It was great publicity all the way around. The Little Caesar’s Casino and Sports Book basked in the glow of publicity as it happily paid the $2,100,000 check (for winnings and original bet) to Stupak. He basked in the light of publicity, as he was seen as the ultimate “macho-man.” He put it all on the line for his team, and he had won.

One newspaperman was rather suspicious about the deal, as it seemed too good to be true for both the casino and the bettor. The newspaperman made an official inquiry of the Nevada Gaming Commission as to the veracity of the bet. The commission confirmed that Stupak had bet $1,100,000 on the game and that his win was legitimate. The commission reported no fact other than it was a legitimate bet. Sometime later, news media personnel uncovered “the rest of the story.” Stupak may have bet on both teams. He may have been a $100,000 loser for the day – but it was worth it to gain the desired publicity, if he had won $1 million on one bet and lost $1.1 million on the other. The Nevada Gaming Commission has absolutely no obligation to report information on losing bets—indeed, that information is rightfully considered to be very private. Publicly, that information certainly would harm the industry, as Las Vegas seeks to portray itself as a place where “winners” play. There was nothing illegal about playing both sides of a sports bet.

Sports betting occurs when gamblers make wagers on the results of games and contests played by other persons. The results of the games and contests are completely independent from the wagering activity of the gamblers. In other words, the gamblers have no control over the outcome of the games – that is, as long as the wagering is honest. Whether it is legal or not is another matter. Sports betting occurs when gamblers make wagers on the results of games and contests played by other persons. The results of the games and contests are completely independent from the wagering activity of the gamblers. In other words, the gamblers have no control over the outcome of the games – that is, as long as the wagering is honest. Whether it is legal or not is another matter.

There are sports betting opportunities with a wide variety of games and contests. Although in a generic sense sports betting includes wagers made on the results of horse races and dog races, these games (contests) are usually considered to be different than other contests. In this encyclopedia, they are discussed separately, as are jai alai contests and betting on dog fights (pit bull fights) and cockfighting.

Sports betting in North America involves many kinds of games. It may be suggested that making wagers on the results of games is the most popular form of gambling in North America. It is certainly the most popular form of illegal betting in the United States.

In Nevada, there are 142 places, almost all within casinos, that accept bets on professional and amateur sports contests. Nearly $2.3 billion was wagered in these sports books in 1998. The casinos kept $77.4 million of this money; that is, they “held” 3.3% of the wagers, owing to the fact that the players bet on the wrong team and also that the casino structures odds in its favor. The sports wagers constituted just over 1% of all the betting in the Nevada casinos. About two-thirds of the wagers were on professional games and the rest on college games (National Gambling Impact Study Commission 1999, 2–14). Although the profits casinos realize directly from sports bets seem to be low, sports betting is very important in Las Vegas and Reno. The major gamblers like to follow sports, and the wagering possibilities draw them to the casinos. Also, the casinos sponsor championship boxing matches and give the best seats to their favorite gamblers. Superbowl weekend is the biggest gambling weekend in Las Vegas each year, as the casinos have special parties, usually inviting sports celebrities (retired) as well as other noted personalities to come and mingle with their gamblers. Of course, many of these invited celebrities turn out to also be heavy gamblers.

In 1998, the Oregon sports lottery sold $8.5 million worth of parlay cards on professional football and basketball games, and the state retained over $4.2 million (50 percent) as its win. This is less than 1 percent of total lottery winnings, but 4 percent of the winnings on non-video lottery terminal lottery games. The sports lottery is structured to produce a return of 50 percent to the players on a pari-mutuel basis.

The National Gambling Impact Study Commission suggested in its 1999 Final Report that illegal gambling activities draw wagers of several hundreds of billions of dollars each year, perhaps as much as $380 billion (National Gambling Impact Study Commission 1999, 2–14). It is likely that the operators of these games hold 3 to 5 percent of the wagers as profits. The illegal sector commands considerably more activity than the few legal outlets for sports gambling in the United States.

Betting has developed rapidly in recent decades. In 1982, the Nevada sports books attracted $415.2 million in wagers and kept only $7.7 million (less than a 2 percent hold). The hold increased an average of 16.6% every year until 1998, after which it leveled off. Only California card rooms and Native American gambling operations had greater annual increases. In comparison, casinos increased 10.4 percent each year and lotteries 13.5% (Christiansen 1999). The added interest in sports betting has been affected by an added interest in sports in the United States. Although individual sports have different experiences with their growth, one factor that has affected all sports has been television access to games and news media on odds and points spreads. Most Nevada sports betting was confined to small parlors outside of the major casinos until the late 1970s. The gambling activity was discouraged by the fact that the federal government imposed a 10 percent tax on each sports wager; however, this was lowered to 2% by 1975. In that year, the amount wagered in Nevada quadrupled. The state of Nevada changed laws in 1976, making it easier for casinos to have sports books. Then, a final breakthrough came in 1982 when Congress lowered the federal betting tax on sports contests to 0.25%, which is where it is today. Major sports betting areas were constructed in many casinos, the largest books (in physical size) being found today in the Las Vegas Hilton and Caesars Palace.

Ironically, given the widespread nature of sports betting, the gambling is also very controversial. Popular opinion on betting is very mixed, and indeed, opinion is more strongly against legalizing this particular form of gambling than are negative factors on any other type of gambling. The survey taken for the Commission on the Review of the National Policy toward Gambling in 1974 found majority acceptance of several forms of gambling – bingo, horse racing, lotteries – whereas fewer than half of the respondents supported legalization of casinos (40%) and offtrack betting (38%), and the fewest supported legalized sports betting (32 percent) (Commission on the Review of the National Policy toward Gambling 1976, App. II). A 1982 Gallup poll found majority support for all other forms of gambling but only 48% approval for betting on professional sports events (Klein and Selesner 1982). Opponents of sports betting suggest that the activity may have a tendency to corrupt the integrity of games, as those making wagers could try to influence the activity of the players in the contests.

Sports betting is authorized in Canada, Mexico, and other parts of Central America and the Caribbean region; however, sports betting is very limited in the US. Actually only in Nevada can a gambler legally make a wager on an individual contest or game. In Oregon the lottery runs a sports game in which the player must select several professional teams playing basketball or football on the same day or weekend. Nonetheless, sports betting is very pervasive in the United States, as bets on almost all sports events take place among friends or fellow workers or among social acquaintances in private settings. Almost all of these wagers, as already discussed, are illegal, as are wagers made through betting agents known as bookies. The appearance of the Internet and the worldwide web, which provide services in a form available to most residents, has led to a substantial increase in the amount of sports betting by Americans, most of which is also clearly illegal. There is some debate, however, as to whether Internet gambling, which is controlled by an operator in a jurisdiction where it is licensed and legal, is always illegal if the player is in another jurisdiction.

The greatest amount of sports betting – both legal and illegal – in the United States consists of wagers made on American football games. The National Football League (professional) games attract the most action, with the championship game (the Superbowl) being the initial attraction, the most wagering “action”. The Superbowl attracts wagers approaching $100 million in the casinos of Nevada, and perhaps fifty times that amount or more is gambled on the game illegally. Most of the illegal gambling on the Superbowl consists of private bets among close friends or participation in office “pools” in which the participants pick squares representing the last digit of scores for each of the two teams. Following the Superbowl in importance for the gambling public are the college basketball championship series, the World Series for professional baseball, and the National Basketball Association (NBA) championship series.

Each kind of game has different structures for gambling. Basically, wagers are made on an odds basis, on a basis involving handicapped points for or against one of the contestants (teams), or on a combination of odds and handicapped points.

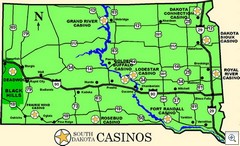

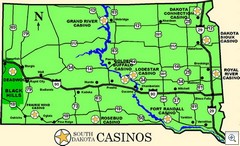

The voters of South Dakota made the state the nation’s third commercial casino jurisdiction at the ballot box in November 1988. The voters in effect amended the state constitution to permit limited stakes gambling, but only in the town of Deadwood. In 1989 the legislature passed an enabling act, and the voters of Deadwood ratified the decision to have casinos in their town. Several casinos opened in November 1989, and there are now over sixty casinos in Deadwood. The ostensible purpose of casino gaming was to generate revenues for tourist promotion and for historical preservation projects in Deadwood. Wild Bill Hickok had been shot in the back while playing poker in Deadwood in 1876, but the town was a decaying relic from that time. The town’s main block of buildings had burned in the mid-1980s. The voters of South Dakota made the state the nation’s third commercial casino jurisdiction at the ballot box in November 1988. The voters in effect amended the state constitution to permit limited stakes gambling, but only in the town of Deadwood. In 1989 the legislature passed an enabling act, and the voters of Deadwood ratified the decision to have casinos in their town. Several casinos opened in November 1989, and there are now over sixty casinos in Deadwood. The ostensible purpose of casino gaming was to generate revenues for tourist promotion and for historical preservation projects in Deadwood. Wild Bill Hickok had been shot in the back while playing poker in Deadwood in 1876, but the town was a decaying relic from that time. The town’s main block of buildings had burned in the mid-1980s.

Prior to casino gaming, the state had permitted dog- and horse-race wagering. The state had instituted a lottery in 1987, and in 1989 the lottery had also began operation of video lottery terminals in age-restricted locations. Each location was allowed twenty machines that awarded, on average, 80 percent of the money played as prizes given back to the players. In the 1990s, nine Native American casinos compacted with the state to operate facilities. The casinos are located at Sisseton, Hankinson, Watertown, Wagner, Lower Brule, Mobridge, Fort Thompson, Pine Ridge, and Flandreau.

The commercial casinos in Deadwood were originally allowed to have thirty games (machines or tables), but as facilities were built together, the state changed the limitation to ninety games each for a single retail location. In addition to machines, which guaranteed prizes equaling 90% of the money played, the only games permitted were blackjack and poker. Bets were limited to five dollars per play. In the poker games the casino could rake-off as much as 10% of the money wagered. The casinos pay 8% of their winnings to the state in taxes; of this, 40% goes to tourist promotions, 10% to the local government, and 50 percent to the state for regulatory purposes. If regulatory costs fall below this amount, the remaining money is dedicated to historical preservation projects.

In 1989, the lottery began using video machines located in restaurants and bars around the state. In 2000, antigambling interests made attempts to stop the lottery machines, but according to the New York Times of 9 November 2000 (B-10), the voters decided to keep them.

During the 1990s, South Carolina became the land of gambling loopholes. During the 1970s and 1980s video game machines began to appear in many South Carolina locations. Cash prizes were given to players who accumulated points representing winning scores at the games. No cash was dispensed by the machines; instead, the owners of establishments with the machines paid the players. Although the arrangements seemed on the surface to violate antigambling laws, they survived legal challenges. In 1991 the state supreme court bought into a loophole that the operators offered in their defense. The operators argued that the machines were not gambling machines as long as the prizes were not given out by the machines directly. The court agreed, and so naturally a gaming machine industry began to blossom throughout the state (Thompson 1999). During the 1990s, South Carolina became the land of gambling loopholes. During the 1970s and 1980s video game machines began to appear in many South Carolina locations. Cash prizes were given to players who accumulated points representing winning scores at the games. No cash was dispensed by the machines; instead, the owners of establishments with the machines paid the players. Although the arrangements seemed on the surface to violate antigambling laws, they survived legal challenges. In 1991 the state supreme court bought into a loophole that the operators offered in their defense. The operators argued that the machines were not gambling machines as long as the prizes were not given out by the machines directly. The court agreed, and so naturally a gaming machine industry began to blossom throughout the state (Thompson 1999).

Operators “seen their opportunity”, as the famous turn-of-the-last-century political philosopher George Washington Plunkitt of Tammany Hall would say, “and they took ’em”. As the gaming revenues flowed in, the operators formed a very strong political lobby to defend their status quo. The legislature addressed the issue of machine gaming, but it could only offer a set of weak rules that have not been rigorously enforced. Legislation provided that gaming payouts for machine wins were supposed to be capped at $125 a day for each player. Advertising was prohibited. There could be no machines where alcoholic beverages were sold, operators could not offer any incentives to get persons to play the machines, and there could be only five machines per establishment. Machines were also licensed and taxed by the state at a rate of $2,000 per year. (Of the tax, $200 is now given to an out-of-state firm to install a linked information system).

The rules have not been followed in their totality. Establishments have linked several rooms, each having five machines. As many as 100 machines have appeared under a single roof. Progressive machines offer prizes into the thousands of dollars. Operators claim they pay each player only $125 of the prize each day. In some cases, they award the full amount of the prize and have the player sign a “legal” statement affirming that the player will not spend more than $125 of the prize in a single day. Advertisements of machine gaming appear on large signs by many establishments. Bars and taverns have machines.

There have been thousands of citations against establishments, and fines have been levied. In 1997 and 1998, there were $429,000 in fines in a nine-month period. The practices did not end, however.

Several interests in the state did not care for gambling. They persuaded the legislature to authorize a statewide vote on banning the machines. According to the legislation authorizing the elections, votes were to be counted by counties. If a majority of the voters in a county said they did not want the machines, the machines would be removed from that county. In 1996, twelve of forty-six counties said they did not want the machines. Before they could be removed, however, the operators won a ruling from the state supreme court saying that the vote was unconstitutional. The court reasoned that South Carolina criminal law (banning the machines) could not be enforced unequally across the state. Equal protection of the law ruled supreme in the Palmetto State.

Over the last years of the 1990s, the legislature and state regulators continued to wrestle with issues surrounding machine gaming. One effort to have all the machines declared lotteries and banned in accordance with a state constitutional prohibition on lotteries failed, as the supreme court held by a single-vote majority that the gaming on the machines did not constitute lottery gaming. The 1998 gubernatorial election seemed to turn on gambling issues, as supporters of machine gaming and lotteries gave large donations to the winning candidate. The new governor has sought to win wide support by initiating new “more effective” regulations, but these have not yet won consensus support in the legislature. One new proposed regulation would allow machines to have individual prizes of up to $500 that could be won on a single play. Another proposal would set up a new state regulatory mechanism for machine gaming.

In the meantime, machine gaming flourishes. At the beginning of 1999 there were over 31,000 machines in operation. They attracted over $2.1 billion in wagers, and operators paid out prizes of $1.5 billion. Machine owners and operators realized gross gaming profits of $610 million – approximately $20,000 per machine per year. Almost all of the machines were made outside of the state. Over half were Pot o’ Gold machines made in Norcross, Georgia. These cost $7,500 each. Most of the operators share revenues with owners of slot machine routes. There has been no mandatory auditing of machine performance, although the state authorized the installation of a slot information system.

In 1999 the voters were authorized by the legislature to decide if the machines should stay or be removed. If the voters did not determine the machines could stay, they had to be taken out. But in a surprise decision, the state supreme court ruled the referendum vote unconstitutional and ordered that the machines be removed by 30 June 2000. In November 2000, the voters removed a constitutional ban on lotteries. A lottery will begin in 2001.

Machine gambling is essentially a house-banked gambling operation. Certainly the player is wagering against a machine. As many states have lotteries or allow only games such as bingo that are played among players, the states have sought to keep Native American tribes from having slot machines of the type that are found in casinos. For instance, in California, the state spent a decade fighting the tribes, insisting that the tribes had to have only machines that were linked together so that players had to electronically pool their money, from which 95% – or some percent – could be awarded as prizes. Only the voters who passed Proposition 1A in March 2000 were able to change the situation, and now by popular approval, the tribes have slot machines. In the state of Washington many tribes agreed to have these pooled arrangements for their machines. Although the state may seek to find some legal technicality that makes pools acceptable and regular slot play unacceptable, the players will have a hard time telling the difference. Moreover, the state is doing a major disservice to the notion that the player should be given an equal chance to make the big win on every play as he is in Las Vegas, rather than having a list of winning prizes that diminishes every time a player takes a win. In Las Vegas and other places with regular slot machines, the machines have random number generators that are activated with each play. The player has the same chance of winning a jackpot, a line of bells, bars, or other prizes with every single pull, and the casinos could conceivably lose on every single pull. It is called gambling, after all.

The reality is, however, that the law of large numbers applies to slot machine play, and the payout rates are very consistent over time. Table 1 shows the rates of returns for each of the casinos in New Jersey, Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa over each month of 1999. Even if the state mandated a specific return, as it does for a lottery or for a bingo game, the returns could not be much more consistent. Note that some states and casinos have better returns than others – actually Las Vegas casinos offer the best returns – consistently over 95 percent. In no way does the different return amount come from any manipulation of the computer randomizer chip in the machines. Quite simply, it comes from the payoff schedule. Two machines can have exactly the same play dimensions, but payout percentage returns to the player can differ greatly simply by setting the win for a certain configuration (say three bells) at 18 rather than 20, or on a poker machine making the wins for flush and full house 5 and 8 instead of 6 and 9. Sophisticated players know the machines, and they can discern the best payout machines by simply looking at the prizes listed on the front of the machines. For obvious reasons, payoffs are better at the higher-denomination machines. A five-cents machine may cost as much to buy as a dollar machine; therefore the casino expects that it needs to hold a higher percentage of the money played on the nickel machines. Actually today all the big casinos have very high denomination machines; indeed, several have machines that take $500 tokens in play – and to win the best prizes on these machines, the player has to play three coins a pull – you would not want to make my mistake on a $500 machine.

Machines have appeal to both the player and the operator. In most cases they can be played alone. The player can study the machine before playing it. It is rare that a player will criticize the way another one plays (I enjoyed one of those rare moments), and with a little study the machine playing is easy to learn. Operators like machines because they do not involve much labor, they are very secure (although cheating has been a historical problem), and they can be left alone to do their job without complaining.

Machine play is the bread and butter for most casinos around the world. Machine gambling offers opportunities pursued by many lotteries and offers the golden hope (or silver bullet) that many feel can save the racing industry. Machines have also crawled into Nevada convenience and grocery stores, and if policymakers allow them, they will be in bars and taverns across the country, all across the globe. It could easily be predicted that machine gambling is the wave of gambling in the future, but now the Internet has come onto the scene, and perhaps it is that machine that will soon be the most lucrative and alluring gambling device.

|