Archive for the “C” Category

Encyclopedia: Gambling in America - Letter C

During the 1950s, Cuba offered the gambler several of the leading casino facilities in the world. There was little doubt, however, that the gaming was connected to organized crime personalities in the United States as well as to military dictator Fulgencio Batista, and both entities skimmed considerable sums from the operations. Cuba also had both public and private lotteries, a first-class racing facility, and jai alai fontons. All the gambling activity came to a halt after Fidel Castro engineered a successful rebellion and took over the reins of power in January 1959. Repeated attempts to negotiate a continuation of casino gaming were unsuccessful, and it has been suggested that U.S. crime interests were involved in attempts to overthrow the Castro regime, both in the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion and in several assassination attempts on the new dictator’s life. The entire tourism infrastructure has slipped into decay during the four decades of Castro rule. Today there are voices suggesting that Cuba may seek to restore its tourism industry and may even contemplate reopening casinos. During the 1950s, Cuba offered the gambler several of the leading casino facilities in the world. There was little doubt, however, that the gaming was connected to organized crime personalities in the United States as well as to military dictator Fulgencio Batista, and both entities skimmed considerable sums from the operations. Cuba also had both public and private lotteries, a first-class racing facility, and jai alai fontons. All the gambling activity came to a halt after Fidel Castro engineered a successful rebellion and took over the reins of power in January 1959. Repeated attempts to negotiate a continuation of casino gaming were unsuccessful, and it has been suggested that U.S. crime interests were involved in attempts to overthrow the Castro regime, both in the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion and in several assassination attempts on the new dictator’s life. The entire tourism infrastructure has slipped into decay during the four decades of Castro rule. Today there are voices suggesting that Cuba may seek to restore its tourism industry and may even contemplate reopening casinos.

The island of Cuba was colonized and controlled by the Spanish government for four centuries, until a revolution developed to a major scale in the 1890s. When the United States declared war on Spain in 1898, the revolution became successful, and independence was gained for the Cuban people. Authorities in the United States, however, sought to keep many controls over the Cuban people. War troops were not removed until 1902, and even after the Cubans elected a new government under President Jose Miguel Gomez that year, the United States “negotiated” to have a major naval base at Guantanamo Bay. Other commercial interests in the United States also maintained an economic domination over much of Cuba, but these interests had been in Cuba for many years before the revolution. Many Americans looked at the seaside location called Marianao, ten miles outside of Havana, and found it to be a desirable place to live, engage in real estate transactions, and start tourism resorts.

A local group known as the 3 C’s (named for Carlos Miguel de Cespedes, Jose Manuel Cortina, and Carlos Manuel de la Cruz) formed a tourism company that sought to build a casino in Marianao. In 1910, they proposed legislation in the National Congress that would permit the casino and would also grant them an exclusive thirty-year concession to operate it. At a time when the Americans in Cuba saw the casino as “opportunity”, Americans in the United States were in a wave of anti-sin social reform. This was the same year that the casinos of Nevada closed their doors and the Prohibition movement was in high gear. U.S. president Howard Taft was lobbied hard by church interests to not allow gambling so close to our shores. During the Spanish American War, President William McKinley had decreed that there be no more bullfighting in Cuba, calling the activity a disgraceful outrage. Taft was expected to bully the Cuban Congress to follow U.S. wishes as well. The legislation failed to pass. A second attempt was made to have casino-tied revenues to support $1.5 million in construction of facilities for tourism in Marianao. One New Yorker, who had a contract to build a jai alai fonton and a grandstand for racing, sought to change Taft’s mind on the issue, but again, casinos were defeated as a result of a moralist campaign in the United States.

Gambling was in the cards for Cuba, however. In 1915, Havana’s Oriental Park opened for horse racing. In 1919, the casino promoters promised that they would build the streets and plazas for Marianao if they could have casinos. President Mario Menocal, who had been elected in 1917, supported a bill for casinos. The national legislature authorized a gambling hall for the resort on 5 August 1919. The 3 C’s group ran the facility. In addition to land improvements for tourism, they agreed to a national tax that was designated for the health and welfare of poor mothers and their children. At the same time, President Menocal’s family won the concession to have jai alai games in Marianao. The tourism push was on, and the United States was the primary market, especially after Prohibition began for the whole country in 1919. The Roaring Twenties roared outside of Havana. Several new luxurious hotels opened, each having a gaming room. Each successive presidency endorsed tourism and welcomed all investors. Even Al Capone opened a pool hall in Marianao in 1928. Then the Depression came.

The 1930s in Cuba were years of reform thinking. Leaders openly condemned the degradation of casino gaming and other sin activities that had been widely offered to tourists. In 1933, the casinos were closed, and Prohibition ended in the United States. The economy floundered. The next year, army sergeant Fulgencio Batista was able to oust President Ramon Grau San Martin and install his own government. He ruled as chief of staff of the army while another held the presidency. At first Batista tried to bolster the notion of cultural tourism, but he could not resist allowing casinos to reopen—under the control of the military. Batista was very concerned about the honesty of the games. For sure, he would be skimming. If players were being cheated, however, there soon would be no players. The house odds could give the casinos enough profits to pay off the generals and the politicians, but not enough to pay off all of the dealers. Games had to be honest. He turned to a person who understood this and other dynamics of the casino industry very well – Meyer Lansky. Lansky took over casino operations, and he imported dealers who would work for him and not behind his back. The Mob cleaned things up. Because of World War II and postwar disincentives for foreign travel by Americans, however, the casino activity was rather dormant through the 1940s. Nonetheless, Havana attracted more persons of bad reputation. In 1946, Salvatore “Lucky” Luciano moved in to conduct heroin trade and to be involved with the Jockey Club and the Casino Nacional. Lansky was influential in persuading the government to expel his competitor.

Fulgencio Batista won the presidency on his own in 1940. In 1944 and 1948, he permitted Grau San Martin and Carlos Prio Socarras to win open elections; however, he remained very much a controlling element. In 1952, while a candidate for the presidency, he sensed he had no chance of victory. Batista executed a coup and took the reins of power. Subsequent elections were rigged, and he remained in power until the beginning of 1959. During this latter period of rule, casino development accelerated.

The 1950s started out slowly for the casinos. Prior to 1950, only five casinos were in operation, and a brief reform spirit in 1950 led the government to close them. Commercial pressures, however, led to a reopening before Batista conducted his coup. The casinos now offered large numbers of slot machines for play. By the mid-decade, new Cuban hotels were attracting large investments from the United States, as the gambling operations were quite lucrative. Foreign operators, however, still had ties to organized crime members. A major incentive for a renewed interest in Cuban gaming came from the Senate Kefauver investigations that were exposing illegal gambling operations in the United States. Organized crime members were being run out of places such as Newport, Kentucky; Hot Springs, Arkansas; and New Orleans, Louisiana. At first, they gravitated toward Las Vegas; then Nevada instituted licensing requirements that precluded their participation in operations there. Cuba, the Bahamas, and Haiti became desired locations. Four of the five largest Havana casinos were in the hands of U.S. mobsters. As newer properties such as the Havana Hilton, the Riviera, Hotel Capri, and the Intercontinental Hotel came on line, Mob hands were involved in the action. Meyer Lansky was always the leader of the group. He kept the games honest, and he kept the political skim money flowing in the correct directions. When someone got out of line, he gave the word, and Batista could make a great show about throwing a mobster out of the country. In addition to enhancing casino gambling, Batista also improved revenues of the national lottery by inaugurating daily games.

In 1958, things seemed to be on a roll just when Fidel Castro gathered strength for his military takeover. Revelations in the New York Times about Mob involvement in Cuban casinos dampened tourist enthusiasm, as did the fear of impending violence. The names of Jake Lansky, Salvatore Trafficante, and Joseph Silesi were added to the lists of unsavory participants in the industry.

Fidel Castro was born in 1926, the son of an affluent sugarcane planter. He attended a Catholic school in Santiago de Cuba before entering the University of Havana as a law student in 1945. There he began his career as a political activist and revolutionary. He participated in an attempt to overthrow the government of Dominican Republic strongman Rafael Trujillo and disrupted an international meeting of the American states in Bogota in 1948. He sought a peaceful way to power in 1952 as he ran for Congress; however, the contest was voided as Batista seized power and cancelled the election. In 1953, Castro took part in an unsuccessful raid on the government; he was captured and imprisoned for a year. He was released by Batista as part of a general amnesty program but kept up his revolutionary efforts, leading another unsuccessful raid in 1956. His third try was his charm, as he successfully moved through rural Cuba during 1958, attacking Havana at the end of the year and driving Batista from office.

When Castro’s forces descended on Havana on New Year’s Eve 1958, there were thirteen casinos in Havana. The hotel casinos represented a collective investment of tens of millions of dollars. Lansky’s Riviera alone cost $14 million. Owners and operators did not want to join Batista in his hasty exile out of the country, even after revolutionary rioters had smashed up many of their gaming rooms. They wanted to hold on to what had been a very good thing. That would be difficult, however. Castro had waged a revolutionary media campaign that condemned the sin industries of Cuba and their connections to the Batista government. Castro had pledged that he would close down the casinos.

Castro was true to his word on this score, at least at the beginning. He also stopped the national lottery from operating. Meyer Lansky, on the other hand, pledged that he would work with the new government, and casinos were temporarily reopened, ostensibly to protect the jobs of their 4,000 workers. The reopenings were short-lived, however. The casinos closed for good (under the Castro regime) in late 1960. Castro’s frontal attack on the Mob and its casino interests in Havana had political consequences in the United States, where the Central Intelligence Agency planned the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion to overthrow Castro and also may have contracted with organized crime operatives to attempt to assassinate the new leader.

The fall of the Batista regime and the end of Cuban casinos had repercussions throughout the gaming industry. Nevada lost its strongest competitive market, and Cuban operatives and owners had to move. The ones that could be licensed went to Las Vegas, as did many of the dealers and other casino workers. Others had to find unregulated or underregulated jurisdictions. Haiti and the Dominican Republic were close at hand, as were the Bahamas. Most of the gaming entrepreneurs in these jurisdictions had Cuban experiences, as did many who went to London to open casinos after 1960 legislation gave unregulated charity gaming halls a green light. Lansky, George Raft, and Dino Cellini were principals in London’s Colony Club until they were expelled from the country. Former Nevada lieutenant governor Cliff Jones of Las Vegas had been active in Cuba. He had made a choice between Nevada gaming and foreign gaming when the “foreign gaming” rule was adopted in Nevada. He chose to be involved in foreign gaming and therefore could not return to Las Vegas. Instead, he began campaigns in one small country after another to legalize casinos and then began operations that he would later sell to (or share with) local parties for high profits. Clearly, the activity of Castro in closing down Havana gaming caused a major spread of gaming elsewhere.

No Comments »

No Comments »

There are several categories of shipboard casino gambling. Gambling on riverboats or other vessels within the waters of a specific jurisdiction is discussed under the entries covering the various jurisdictions (e.g., Illinois). The two categories discussed in this entry include ocean or high seas cruises and voyages and what have come to be known as “cruises to nowhere”. There are several categories of shipboard casino gambling. Gambling on riverboats or other vessels within the waters of a specific jurisdiction is discussed under the entries covering the various jurisdictions (e.g., Illinois). The two categories discussed in this entry include ocean or high seas cruises and voyages and what have come to be known as “cruises to nowhere”.

Voyages on the High Seas

The shipboard cruises encompass destination vacation activities for passengers. Typically, the cruises last several days or even weeks. The ships are luxurious, the cruises are expensive, and the amenities aboard the ships are many—food, dancing, sports activities. Casino gambling has been an activity on more and more of the cruises. The leader among the cruise companies having casinos aboard their ships is Carnival Cruise Lines, with more than forty ships offering casino games. Carnival has a gambling staff exceeding 1,000 individuals for its ships. The ships offer linked slot machines among several vessels, permitting megajackpots. Other major cruise lines with casinos include Holland American Line, Norwegian Cruise Line, Princess Cruises, and Royal Caribbean International.

These ships must operate their games on the high seas, and their voyages are essentially international. They stop at several seaport cities on their venture – at least two of which are in different jurisdictions (countries). While in port, no casino gambling is allowed.

The ship lines listed above are not U.S. companies. Indeed, very few U.S. ships have casino gaming, and very few have luxury cruises either. In 1949, the U.S. Congress passed very strict prohibitions banning gambling on U.S. flag vessels no matter where they were operating, whether in territorial or international waters. The ban affected vessels registered as U.S. and also ones principally owned by U.S. citizens. Although the point of the law was clearly to regulate the type of gambling ship discussed as cruises to nowhere, the effect was general. Even though the law was to apply to ships that were used “principally” for gambling (a rather vague term); U.S. ships ceased to have casinos on their voyages.

The Johnson Act of 1951 made possession of gambling machines illegal except under certain circumstances (e.g., they were legal in the jurisdiction where they were located). This law gave an emphasis to the notion that U.S. ships could not have machine gambling and come into any U.S. port where state law prohibited the machines (which included every port city in the United States in 1951). Foreign vessels could stop the use of the machines in these ports and not be in violation of the 1951 law, as they were still under foreign or international jurisdiction to some degree while in port.

By 1990, the cruise ship industry was flourishing. Over eighty cruise ships utilized U.S. ports. All but two flew foreign flags. Moreover, the general state of U.S. shipbuilding and U.S. companies operating sailing vessels was one of deterioration. In 1991, the U.S. attorney general ruled that a ship was not a “gambling ship” if it provided for overnight accommodations and/or landed in a foreign port on its cruise. U.S. shipping companies renewed an interest in offering gambling on cruises. As a result, Congress passed the Cruise Ship Competitiveness Act on 9 March 1992 in order to establish “equal competition” for U.S. ships. Now the U.S. flagships can have gambling on their cruises while in international waters.

The international cruise ships are, for the most part, not subject to the regulation of any jurisdiction regarding their gambling activities. There are few limitations on licensing of casino managers or employees and few guidelines on surveillance and player disputes. Nonetheless, the major cruise ship companies have considerable internal regulations. Most have definite limits on the amounts of money that can be wagered, as they do not wish to take opportunities for spending money on other amenities away from the passengers, who may have to remain on the ship for several days after their gambling venture has ended. As Carnival Cruise Lines and other ship casino companies (Casinos Austria runs several of the casinos) have land-based operations in other jurisdictions (Carnival is in Louisiana and Ontario), they do not want to have their licenses there jeopardized by any unacceptable practices within their shipboard casinos.

There is one ship on the high seas that has been subjected to the direct regulation of a state. Nevada requires its casino license holders to secure permission of the Nevada Gaming Commission and the Gaming Control Board if they are operating gambling operations outside of the state. Prior to 1993, the permission had to come from the state authorities before out-of-state operations could begin. Accordingly, in 1989 Caesars Palace applied for approval to manage the casino on board the Crystal Harmony, an exclusive Japanese-owned ship flying the flag of the Bahamas. The approval was granted under the condition that Caesars establish a fund for the Nevada gaming authorities so that the state could conduct background investigations of the ship owners, operators, and crew. Internal auditing controls also had to meet state standards, with independent accountants conducting regular reviews of the books. Nevada agents were given full access to the casino’s records, as well as to the facilities. Caesars absorbed all costs of regulation. The Crystal Harmony was the first and only international ship to have a casino regulated by the jurisdiction of a state of the United States.

Cruises to Nowhere

The 1949 act banning gambling on U.S. flagships resulted from a controversy lasting several decades in California and other coastal states. Starting in the 1920s, floating barges appeared in the waters off of San Francisco and Los Angeles, as well as off the Florida coast. The ships anchored in international waters—three miles off the coasts. They had brightly lighted decks that could be seen from shore and beyond. Each day and evening they would provide boat taxi service for customers from nearby docks. The ships had entertainers, food, drinks (it was Prohibition time), and gambling. They operated through the 1930s without much opposition from law enforcement. When Earl Warren became attorney general of California, however, he decided to crack down. Raids were conducted, but the issue of what was definitely legal or illegal persisted until U. S. senator William Knowland of California persuaded his congressional colleagues to pass legislation in 1949. The law now had teeth and was enforced until there was pressure for change in the 1990s.

Even before the passage of the 1992 Cruise Ship Competitiveness Act, vessels began to test the resolve of states and the federal government regarding coastal gambling operations. The actions of one company seemed to be the catalyst for the legalization of riverboat and coastal casinos in Mississippi in 1990. After the 1992 legislation passed, the states were given the opportunity to opt out of the Johnson Act prohibition on machines in their waters. Hence, they could allow boats to have cruises out to international waters for gambling even if the boats did not stop at foreign ports. In 1996, the U.S. Congress acted again. This time Congress gave a blanket approval to the international waters’ “cruises to nowhere” unless the state (of debarkation and reentry) specifically prohibited the gambling ships. The state could only prohibit them if the ship did not make port in another jurisdiction. The ship’s gambling operations would not be subject to any jurisdiction unless, again, the state took specific action for regulation.

Since the 1996 law was passed, a large number of ships have begun operations off of Florida and also in the northeast. The state of California specifically passed a ban on the ships. Over twenty-two ships operate off of Florida, generating collective revenues of well over $200 million a year. Ships also have used South Carolina ports. Several ships attempted to gain docking rights in New York City, but local officials, including Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, fought the efforts and demanded that the boats go out to at least twelve miles off the coast before they could have gambling. After many months of negotiations, the city agreed to establish a gambling regulatory board for the ships through passage of an ordinance. One major vessel, the Liberty I, agreed to follow the local regulations.

Several states, including South Carolina and Florida, have found opponents of the boats seeking legislation against them, but so far their efforts have been to no avail. Even California has succumbed to the realization that regular gambling cruises for local residents have come to be. On 15 April 2000, the Enchanted Sun began voyages out of San Diego. The ship goes out three miles and hugs the coast until it reaches Rosarito Beach, south of Tijuana, Mexico. It hits the dock, briefly drops anchor, and then returns. The ship is at sea for a total of less than eight hours. In each trip, over 400 passengers enjoy a meal, entertainment, drinks, and gambling. Commercial success of such operations is not guaranteed. Passengers have to pay a cruise fee of $68, and as with other ships, there is always the problem of rough seas. An interesting twist to the Enchanted Sun casino is the fact that the California Viejas Band of Native Americans is an operating partner in the venture on the high seas.

No Comments »

No Comments »

The crime issue has been and will continue to be an essential issue in debates over the legalization of gambling. Opponents of gambling make almost shrill statements about how organized crime infiltrates communities when they legalize gambling. They also suggest that various forms of street crimes – robberies, auto-thefts, prostitution – come with gambling, as do embezzlements, forgeries, and various forms of larceny caused by desperate problem gamblers.

On the other hand, proponents of gambling contend that the evidence of any connections between crime and gambling is rather weak. They contend that the stories of Mob involvement with gambling are a part of the past, but not the present, and that even then the involvement was more exaggerated than real. Most cases of increased street crime are passed off as owing to increased volumes of people traffic in casino communities. Moreover, proponents of legalized gambling even argue that because gambling may lead to job growth in gambling communities, crime may actually go down, the reason being that employed people are less inclined to be drawn to criminal activities than are people without jobs. They also suggest that by legalizing gambling, society can fight the effects of illegal gambling.

Opportunities for Crime

Criminologists have identified opportunity as a factor in explaining much criminal activity. The kinds of crimes that are purportedly found in association with gambling indicate the efficacy of “opportunity” theories of crime. For instance, the several types of crime that might be associated with the presence of casinos include inside activity concerning casino owners and business associates and employees, crimes tied to the playing of the games, and crimes involving patrons. Organized crime elements may try to draw profits off the gaming enterprise through schemes of hidden ownership or through insiders who steal from the casino winnings. Managers may steal from the profit pools to avoid taxes or to cheat their partners.

Organized crime figures may become suppliers for goods and services, extracting unreasonable costs for their products. Crime families have been the providers of gambling junket tours for players and, in New Jersey, for various sources of labor in the construction trades. Organized crime figures also may become involved in providing loans to desperate players, and the existence of the casinos may facilitate laundering of money for cartels that traffic in illegal activities such as prostitution and the drug trade.

Another set of crimes attends the actual games that are played. Wherever a game is offered with a money prize, someone will try to manipulate the games through cheating schemes. Cheating may involve marked cards, crooked dice, and uneven roulette wheels. Schemes may involve teams of players or individual players and casino employees. Cheating is also associated with race betting and even with lotteries. In some cases, the gambling organization may attempt to cheat players.

The greatest concern about crime and gambling involves activities of casino patrons. On the one hand, they present criminals with opportunities. Players who win money or carry money to casinos may be easy marks for forceful robberies as well those by pickpockets. Hotel rooms in casino properties are also targets. Players are targeted by prostitutes and also by other persons selling illicit goods, such as drugs. On the other hand, desperate players may be drawn to crimes in order to secure money for play or to pay gambling debts. Their crimes involve robberies and other larcenies, as well as white-collar crime activity—embezzlements, forgeries, and so on.

Studies of Crime and Gambling

The issue of crime and gambling has been well studied for generations. Virgil Peterson, director of the Chicago Crime Commission, issued a scathing attack on gambling in his Gambling: Should It Be Legalized? (1951). He asserted that “legalized gambling has always been attractive to the criminal and racketeering elements” …. “[C]riminals, gangsters, and swindlers have been the proprietors of gambling establishments” …. “[M]any people find it necessary to steal or embezzle to continue gambling activity” (120–121)…. “The kidnapper, the armed robber, the burglar and the thief engage in crime to secure money for play”.

In a 1965 article that seemed prophetic, considering future events in New Jersey, Peterson wrote, “The underworld inevitably gains a foothold under any licensing system. If state authorities establish the vast policing system rigid supervision requires, the underworld merely provides itself with fronts who obtain the licenses, with actual ownership remaining in its own hands; and it receives a major share of the profits” (Peterson 1965, 665).

Other stories of the relationships between organized crime and gambling are plentiful. While Peterson was gathering information for his book, the Senate Committee on Organized Crime was holding hearings under the leadership of Estes Kefauver in 1950 and 1951. The committee was specific in identifying gambling as a major activity of organized crime.

In the 1960s, Ovid Demaris and Ed Reid wrote the Green Felt Jungle (Reid and Demaris 1963), a shocking account of the Mob in Las Vegas. Demaris continued the saga with his Boardwalk Jungle (Demaris 1986), an early account of casinos in New Jersey. His story was built upon a journalistic account of crime involvement in Atlantic City’s first casino by Gigi Mahon, The Company that Bought the Boardwalk (1980). The role of organized crime was tangential to the activities of the first company that won a casino license in New Jersey and persisted with involvement in labor unions that served companies constructing the casino facilities.

The issue of organized crime and gambling has lost much of its punch over the past thirty years, however, as major corporations have emerged as the most important players in the gambling industry. Nonetheless, gaming control agents and other law enforcement agencies from the local, state, and federal levels must remain vigilant lest organized crime elements return to the gambling scene. In reality they have never completely left the scene. In the 1990s, they were still found seeking inroads to the management of casino operations in one San Diego County Native American casino. They actually infiltrated the operations of the White Earth Reservation casino in Minnesota, and the tribal leader was indicted for wrongdoing in connection with his Mob ties. The slot machine operations in restaurants and bars of Louisiana were compromised by organized crime elements, and indictments ensued. As the twentieth century ended, organized crime interests maintained ties with several Internet gambling enterprises operating in other countries.

The major concern over gambling has, however, turned toward ambient crime – personal crime that appears in the atmosphere around gambling establishments. In September 1995, L. Scott Harshbarger, Massachusetts state attorney general, commented to the U.S. House Judiciary Committee that “one of the noted consequences of casino gambling has been the marked rise in street crime. Across the nation, police departments in cities that have casino gambling have recorded surges in arrests due to casino-related crime. In many cases, towns that had a decreasing crime rate or a low crime rate have seen a sharp and steady growth of crime once gambling has taken root….” (Quoted in Gambling under Attack 1996, 785). Although there were many statements from law enforcement officials that echoed Harshbarger’s thoughts, there were also those who disputed the claims.

Empirical Studies

Much of the data for the studies mentioned above was anecdotal or came from personal testimony of law enforcement personnel. Other entries into the literature have been based upon similar kinds of evidence. Such studies may be interesting, but they have only a limited value. Anecdotes may not always be precise or accurate.

More solid data have come from analyses of criminal statistics. George Sternlieb and James Hughes’s study of Atlantic City revealed that crime increased rapidly in the community after the introduction of casinos in 1978. Pickpocketing activity increased eighty-fold, larceny increased over five times, and robberies tripled, as did assaults (Sternlieb and Hughes 1983, 192). Simon Hakim and Andrew J. Buck found that the levels of all types of crime were higher in the years after casinos began operations. The “greatest post-casino crime increase was observed for violent crimes and auto thefts and the least for burglaries” (Hakim and Buck 1989, 414). As one moved farther from Atlantic City in spatial distance, rates of crime leveled off (415). On the other hand, Joseph Friedman, Simon Hakim, and J. Weinblatt found that increases in crime extended outward at least thirty miles to suburban areas and to areas along highways that extended toward New York and Philadelphia (Friedman, Hakim, and Weinblatt 1989, 622).

Similarly a study of Windsor, Ontario, found some crime rates increasing after a casino opened in May 1994. Overall, previous decreases in rates of crime citywide seemed to come to an end, whereas rates in areas around the casino increased measurably. The downtown area near the casino found more assaults, assaults upon police officers, and other violent crimes. Particularly noticeable were increases in general thefts, motor vehicle thefts, liquor offenses, and driving offenses (Windsor Police 1995).

Not all the evidence points in the same direction. Several riverboat communities in Iowa, Illinois, and Mississippi saw decreases in crime rates following the establishment of casinos. Moreover, several scholars, including Albanese (1985, 44) and Chiricos (1994), demonstrated that higher incidents of crime in Atlantic City were a result, in large part, of increases in visitor traffic. If numbers of tourist visitors were included in permanent census figures, crime rates would be stable or might even be less than they were before casinos came to Atlantic City. A study by Ronald George Ochrym and Clifton Park compared gaming communities with other tourist destinations that did not have casinos. They found that rates of crime were quite similar. Although crime statistics soared following the introduction of casinos in Atlantic City, so too did crime in Orlando, Florida, following the opening of Disney World. If the casinos themselves were responsible for more crime, gaming proponents suggest that Mickey Mouse also must cause crime (Ochrym and Park 1990).

Casino proponent Jeremy D. Margolis, a former assistant U.S. attorney, discounts the crime factors as well. In a December 1997 study for the American Gaming Association, he summarized the literature of crime and gambling studies by pointing to these conclusions: “Las Vegas, Nevada has a lower crime rate and is safer than virtually every other major tourist venue. Atlantic City, New Jersey’s crime has been falling dramatically since 1991. Joliet, Illinois [a casino community] is enjoying its lowest level of crime in 15 years. Crime rates in Baton Rouge, Louisiana have decreased every year since casino gaming was introduced” (Margolis 1997, 1).

My study (Thompson, Gazel, and Rickman 1996) found a mixed pattern of crime and gambling associations in Wisconsin. We examined crime rates for major crimes and arrest rates for minor crimes in all seventy-six counties from 1980 to 1995. Our analysis compared counties with casinos to other counties. We also considered the impacts of crime on outlying nearby counties. We considered all crime data prior to 1992 to be data from counties without casinos. We looked at the incidence of crime in fourteen counties with casinos for 1992, 1993, and 1994 as data from casino counties, whereas 1992, 1993, and 1994 data from other counties was considered noncasino county data. We utilized a technique called linear regression for our analysis.

The introduction of casinos did impact the incidence of serious crimes in the casino counties and counties adjacent to two casino counties. For each 1 percent increase in the numbers of major crimes statewide, the numbers of major crimes in the casino and adjacent counties significantly increased an additional 6.7 percent. Reduced to simple language, the existence of casinos (or nearness of casinos) in the selected counties explains a major crime increase of 6.7 percent beyond what would otherwise be experienced in the absence of casinos. As there were approximately 10,000 major crimes in these counties in 1991, we can suggest that casinos brought an additional 670 major crimes for each of three years after casinos came. The largest share of casino-related crimes were burglaries (10).

Our analysis of Part II (minor crimes, as defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI]) looked at data on the numbers of arrests in each county of the state. Overall, we found that increases in arrests for all Part II crimes in casino counties and counties adjacent to these counties constituted a number 12.2 percent higher than that found in other counties. Although Part II arrest numbers overall are related to the presence of the casinos in Wisconsin, not all categories of Part II arrests could be linked to the casinos. Relationships could be demonstrated for arrests for assaults, stolen property, driving while intoxicated, and drug possession.

Assaults increased 37.8 percent more in these counties than for the state as a whole. Arrests for stolen property increased 28.1 percent more in the casino-adjacent counties. Certainly this finding complements the demonstrated increase in incidents of burglary. Drunk driving arrests increased 13.9 percent more in the casino and adjacent counties than in the other ones, and drug possession arrests increased an extra 21.9 percent. Although the percentage increase was not as great as for some other categories, the most significant relationship between the presence of crime and casinos was driving while intoxicated.

Although the general comments and anecdotal evidence suggest ties between casinos and forgery, fraud, and embezzlement, no strong linkages were found in our data. We did find significant associations between casinos and forgery and fraud within the casino counties, but these relationships did not extend to surrounding counties. No relationships were established with embezzlement arrests. This does not mean they might not exist at a future time. This kind of crime, when it is linked to gambling, takes time to develop. This type of crime is also associated with problem or pathological gambling. First, the cycle of pathological gambling takes time to develop. Second, as the cycle is developing, the pathological gambler is using all possible legal means to get funds for gambling. Only in later desperation stages will the gambler turn to illegal means for funds.

The presence of additional crime also imposes additional costs on the society. We used standard criminal justice costs of arrests, court actions, probation, and jail time, as well as property losses, in our analysis. We concluded that an additional 5,277 serious crimes per year cost the public $16.71 million, and an additional 17,100 arrests for Part II crimes cost society $34.20 million each year. The data suggest that casinos may be responsible, directly or indirectly, for nearly $51 million each year in societal costs due to crime generated as a result of their existence.

Political Crimes and Gambling

Gambling interests (and potential gambling interests) have money. Often their profit margins may be very large, especially in monopoly or semimonopoly situations. The interests are willing to spend their money to advance their causes. The very open bribery of Louisiana legislators in the late nineteenth century by operators of the state’s lottery led to the reforms that ended that lottery and precluded the reestablishment of any state lottery until 1964. Gambling interests will still invest large sums of money into political action. Often their targets are referenda campaigns. The California Proposition 5 campaign of November 1998 was the most expensive ballot initiative campaign in U.S. history. Nevada casino interests put $26 million into the campaign, and tribal gambling interests in California invested nearly $70 million. Prior to 1998, a 1994 campaign to legalize casinos in Florida that drew almost $18 million from the casino industry had been the most expensive referenda campaign in history.

The casinos and other gambling enterprises also invest large sums of money in lobbying campaigns and public persuasion campaigns. This is the political process in the United States, one that thrives on the clash of interests and the clash of issues. It is a Madisonian system in which rival interests protect their turf by making their positions known and by commandeering the facts that will help them persuade policymakers that they are on the correct side when the issues rise to decision points on the public agenda.

Some of the interest might go too far. After all, the potential benefits can be extraordinary. In some jurisdictions, forces desiring casino licenses or contracts with government-controlled gambling operations have crossed the line. A former governor of Louisiana, Edwin Edwards, was a leader in the efforts to get casinos and gambling machines into his state. Rumors about bags of money being brought into state offices filled the air from the beginning—but those are just rumors. Federal Justice Department officials gathered the facts, and he was indicted more than once for taking bribes. The new century began with the former governor on criminal trial; since then he has been convicted and awaits incarceration. Officials in Missouri were charged with the same kind of wrongdoing, and several resigned during the 1990s. One Las Vegas gambling interest withdrew from pursuing casino activity in Missouri because of the exposure of political activities considered inappropriate. Another company remained an active Missouri player but only after removing key company officials. In the 1980s, both Atlantic City and Las Vegas were rocked by FBI sting operations, which involved undercover agents offering bribes to influential public figures in exchange for their intervention in the casino licensing process. The Atlantic City operation – called ABSCAM (a code name based on Arab and scam)—resulted in the resignation of U.S. senator Harrison Williams (D-New Jersey) from office. Several local officials in Nevada saw their political careers also end when they were exposed for taking bribe offers.

Lines between acceptable and even honorable political activity and unacceptable or even illegal activity can be blurred. The incentive remains, however, for continued activity and even intense activity. Citizens, political leaders, law enforcement officials, and industry operatives must always be on watch for wrongdoing; if they are not, the industry will suffer in the long run.

Legalization as a Substitute for Illegal Gambling

Advocates of legalizing gambling suggest that there is a certain quantity of illegal gambling existing in any society and that the process of legalization will serve to eliminate the illegal gaming and channel all gambling activity into a properly regulated and taxed enterprise. As with the other evidence, the research here is also mixed. Nevada certainly had a large amount of illegal gambling before “wide-open” casino gambling was legalized in 1931. Since 1931, there has been very little evidence of illegal casino gambling games in Nevada. Illegal operators simply obtained licenses from the state government.

Similarly, David Dixon found that illegal bookmaking was effectively replaced by legal betting when Great Britain passed legislation in 1960 permitting betting shops (Dixon 1990). Opposite results have been found elsewhere, however. An examination of casinos in Holland by William Thompson and J. Kent Pinney found that legalization in 1975 seemed only to promote an expansion of illegal casinos that had operated before laws were passed for government-operated casinos (Thompson and Pinney 1990). Clearly the illegal operators were not permitted to win licenses. Also, the government placed many restrictions on its own casinos—they had to be located (at first) outside cities; they could not advertise, give complimentary services, or operate around the clock. Illegal casinos found new places to advertise—at the doors of the legal casinos when they closed at 2 a.m. David Dixon also found that when Australia established its government-operated betting parlors, illegal sports and race betting underwent a major expansion (Dixon 1990). Additionally, Robert Wagman explained that the efforts to get rid of the illegal operators in the United States might actually have achieved an opposite effect (Wagman 1986).

Some law enforcement officials are now saying that indications are that the lottery may actually be helping the illegal game. Players are being introduced to the numbers concept in the state-run game, and then they switch to the illegal game when they realize they can get a better deal. The legal state game has solved the perennial problem faced by the illegal games of finding a commonly accepted, and widely available, three-digit number to pay off on. Most of the illegal street games now simply use the state’s three-number pick (Wagman, 1986).

No Comments »

No Comments »

In 1990, I visited the Casino Copanti in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. The casino owners were an American, Eddie Cellini, and his sons. Members of Cellini’s family had previously worked in casinos in Havana, Cuba, and Lagos, Nigeria. I was talking with one of his sons when a player approached the cage and seemed to purchase a full tray of tokens. I thought nothing about it until the same man returned ten minutes later and purchased another full tray of tokens. I commented to the younger Cellini that the man appeared to be a “high roller.” He laughed and said, “No, he is buying tokens to loan to the players”. He went on to add that the tokens were sold at a discount to certain individuals. Those individuals would then know which players they could loan them to with a good expectation of being paid back. The individuals made their own loan and collection arrangements with the players. The casino management endorsed the practices. They had learned several things when they first opened up and made loans directly to the local players. They learned that they were “the ugly Americans” when they tried to collect repayments from players who had been losers. Often the players would say, “I gave you your money back at the tables.” Then they would suggest that the casino’s request for repayment was an affront to their “manhood” and dignity. When the Cellinis went to court to collect the debts, they found judges who were quite reluctant to support the cause of the foreigners from the casino who were now seeking to “exploit” the local players. The casino’s solution was simple—let the locals borrow from each other. I questioned if this might represent casino support for loan sharking but was assured that the loan agents were respected local businessmen and that the casino had never heard of a complaint that their collection procedures were anything but fair.

The Jaragua Casino of Santo Domingo loaned chips to players directly. They had two sets of chips, however. The set of chips that were loaned to players had white stripes across them. The casino manager told me that they had had problems with players borrowing funds to gamble and then cashing in the chips and not repaying the loans on time. Credit players could only win striped chips. The players could not cash these until their debts were fully paid.

Gambling credit and indebtedness pose many issues for the gambling industry. There are simple business decisions, such as: Can the person borrowing money from the establishment be trusted to pay it back? There are also legal questions. For instance, can an establishment go to court to force repayment of a gambling debt? Moral issues confront the industry when casinos may offer loans to players who are not in control of their play (e.g., compulsive gamblers). Other questions concern the use of credit card machines and automated teller machines (ATMs) in gambling places. There is also concern expressed in gambling jurisdictions about the presence of “loan sharks” representing organized crime interests.

Without credit, many large gambling casinos would not be able to sustain ample profits to support their operations in a viable manner. Perhaps half of the table play at Las Vegas Strip casinos is credit play. High rollers appreciate being able to set up accounts with casinos upon which they can draw and also be able to draw upon credit allotments as well. As with the credit card machines or an ATM, this ability permits the player to come to the casino without having to carry large sums of money. Also, winnings can be placed back into accounts instead of being converted into cash that would have to be carried out of the casino on one’s person. This latter situation remains a major problem for casino ATMs, as they allow only withdrawals but no deposits.

By establishing accounts with a casino, a high roller can begin to establish a record of play activity. This enables the casino to award the good player with complimentaries such as free transportation (air flights), free hotel rooms, meals, beverages, and show tickets. Additionally, by engaging in straight credit play, the player and the casino can avoid the necessity of reporting large cash transactions as required by the Bank Secrecy Act of 1970. This may give the player an added sense of anonymity.

In jurisdictions where gambling credit is permitted (as in Nevada and New Jersey), there are usually detailed rules surrounding the loans. In Nevada, regulations require casinos to check the credit history of players seeking loans. They must also look at the previous loans given to the player to be assured that they were repaid. They must also check with other casinos regarding the player’s activity. Casinos are required to check identifications when players cash checks. In actuality, the credit loan from the Nevada casino is like a bank counter check. The credit instrument is called a marker, and it contains information about player bank account numbers and authorizes loan repayments for the accounts. It also acknowledges that the loan was made entirely within the state of Nevada and that the player is willing to be sued in courts, including Nevada courts, for repayment if necessary. The player also agrees to pay the cost of collection.

“In the old days”, casinos may have resorted to ugly tactics to retrieve money owed by players. Nowadays such tactics as threatened physical harm or embarrassments bordering on blackmail are hardly ever used. If they were used and discovered, casinos would be severely disciplined. Most players truly want to replay loans. One major consideration many have is that they will not be able to return to the casino to play again with VIP (very important person) treatment unless they repay the loans. If they are temporarily without sufficient funds, casinos will give them a “long leash” – that is, adequate time to get the necessary resources. Casinos will also discount loan amounts to ensure quick repayment.

Discounts may be as much as 25 percent of the value of the loan. Of course, the casino would have a record that the debtor actually lost the money while playing in the casino. Casino loans that are repaid in a reasonable time do not carry any interest. This factor distinguishes the casino loans from those received from loan sharks. Typically, the loan shark requires a repayment with 10 percent interest per week. If the person cannot make the total repayment, then only the 10 percent is accepted (that is mandatory), and the full loan plus the 10 percent interest carries over until the next week. Casinos in Nevada may use collection agencies that are bonded and licensed; in New Jersey, casino organizations do all the collection activities themselves.

The casinos must make a bona fide effort to collect all debts. Otherwise, they will be assessed taxes as if they had collected the debt in full. New Jersey limits the amount of “bad debt” that can be deducted from their casino win for taxation purposes.

Most North American jurisdictions follow the edict of the Statute of Anne (1710), which became part of the common law of England. The statute holds that debts incurred because of gambling represent contracts that are unenforceable by courts of the realm. Before 1983, Nevada also followed the Statute of Anne. As the Nevada law would apply anywhere as long as it pertained to a Nevada debt, the casinos could not collect debts from out of state, even if the debtor’s state permitted collection of gambling debts through the courts. In 1982, a federal tax court ruled that uncollected Nevada debts could no longer be subtracted from casino wins for tax purposes. Although the decision was overruled by other courts, Nevada was stimulated into action for change. Also, with the advent of New Jersey casinos and the fact that New Jersey courts allowed collection of gambling debts, Nevada casinos found themselves at a disadvantage. Players with debts in both states were paying off the New Jersey debts and ignoring the Nevada debts when they did not have sufficient funds to cover both. In 1983, Nevada repealed the Statute of Anne, and now gambling debts may be collected through courts in Nevada as well as New Jersey.

Even with the Statute of Anne repealed, both states found that other states’ courts would still refuse to order repayment of the loans. Hence, casino operators in Nevada and New Jersey have adopted another method for collection. In Nevada, casinos take their cases only to Nevada courts. There, the facts support them; the courts give judgments in favor of the casino against the debtors. The court ruling is then entered into the courts of the debtor’s home state. Those courts then will issue orders supporting the Nevada court rulings and will not consider the gambling issue. Fortunately for the casinos, debt matters do not have to go to court very often.

A gambling debt is, in effect, the result of a contract between the casino and a player. When a player is taken to court to repay the debt, he or she may offer several defenses regarding the contract, perhaps making a case that the gambling activity in question is illegal. If proven, that would make the contract for a loan illegal and unenforceable. The gambling debtor may also claim that the debt is excessive and that the casino should not have allowed him or her to incur such a large debt. Puerto Rican courts have entertained such defenses and have actually reduced the amount of the debt they ordered to be repaid.

If the player is too young to gamble, age is a complete defense against compulsory repayment of the loan. In a reverse case, a nineteen-year-old was denied a $1-million jackpot he “won” at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. Even though Caesars was in a sense indebted to the player to pay the amount, the casino did not do so. The gaming control board and the courts voided the casino’s obligation to pay the jackpot, because the player was too young to gamble.

Some have argued that the debts from gambling should not have to be repaid if the player was intoxicated. Courts have heard such cases, although they have not ruled in favor of such a debtor. A special defense heard in many cases today is that the player was a compulsive gambler. In such situations, the player must have proof that the casino knew of the compulsive condition prior to the debt. There have also been third-party suits from family members or victims of embezzlement seeking recovery of moneys gambled by compulsive gamblers. There have been some out-of-court settlements in these cases, but as of yet, no major decisions have disallowed collection of debt or given recovery because of compulsive gambling. Efforts continue, however, to bring such cases to court.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

Hazard

Hazard is an old English dice game that contains elements of today’s craps game. Knights played hazard as early as the twelfth century during the crusades to Arabia and the Middle East. It was not until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, however, that hazard became the most popular English casino game.

In basic hazard, a shooter throws two dice. He throws and rethrows until he gets a 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9. This number then becomes his “point.” He rolls again (and again), until a game-ending number comes up. He wins if he makes the point and also if he rolls an 11 or 12 (with some exceptions). He loses if he rolls a 2 or 3 (called a crabs). With a 4 or 10, he rolls again. If he rolls a 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9 that is not his point, it now becomes his “chance”, and he loses if he rolls it again (which means he rolls it before he rolls his point or a 2, 3, 11, or 12).

For a player making rolls over and over, the game was not difficult to understand, although it certainly seems to be a complicated game. To make matters more confusing, many variations were added to the game as time passed. When the game was brought to the North American colonies, the craps version was introduced, and this version was accepted as the standard two-dice game in North America. A three-dice game called grand hazard was also widely played in the colonies. The games of chuck-a-luck and sic bo became a variation of grand hazard.

Chuck-a-Luck

Chuck-a-luck is a three-dice game also known as “bird cage.” Three dice are placed into a large cage shaped like an hourglass. The cage is on an axis, and it is rotated several times by a dealer. The dice fall, and their numbers total from 3 to 18 (each die showing a 1 to 6). A player may bet that a certain number (1 to 6) will show on at least one die. If it does, he or she receives an even-money payoff; if the number appears on two dice, the payoff is two to one; if all three dice show the number, the payoff is three to one. Although the bet appears to most casual observers to favor the player, the house actually has a 7.87 percent advantage.

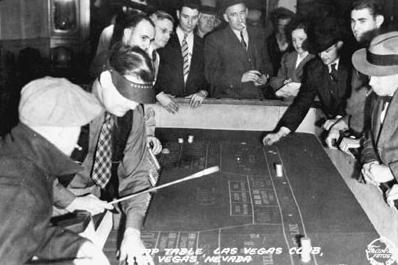

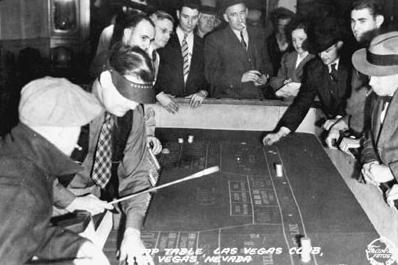

A game of craps in a Las Vegas casino, ca. 1940.

Chuck-a-luck is a three-dice game. Here it is played by the editor and David Nichols (in author biographies) at a charity casino event in El Paso, Texas.

Other bets could also be made. For instance, a player could wager that there would be a three of a kind on a particular number, or any three of a kind. A player could also bet on a high series of numbers or a low series of numbers.

Casino Craps layout. Many different bets are allowed in this most popular dice game.

Sic Bo and Cussec

Sic bo and cussec are two variations of chuck-a-luck. Sic bo is popular in Canada; cussec is played in many Asian countries, as well as in Portugal. Until 1999, no dice were allowed in Canadian games. Sic bo was played in some rather unique ways. A casino in Vancouver had players roll three small balls into a roulette wheel marked with the faces of two dice on each number area (thirty-six markings). At the charity casino in Winnipeg’s Convention Centre (open for a few years during the 1980s), there was an actual slot machine that had three reels. On each reel was the face of a die. The three die faces became the player’s “roll”.

French Bank

French bank is a very fast three-dice game played in Portugal. It is one of the most popular games in Portuguese casinos. The three dice are thrown rapidly until a low series (5, 6, or 7) or a high series (14, 15, or 16) comes up. Players wager even money on low or high. If three aces (1–1–1) come up, all players lose, except those betting on the three aces – they win a sixty-to-one payoff.

Backgammon

Backgammon is a game played with two dice and a board. It involves moving tiles around a playing surface and also blocking movements by one’s opponents. The game is considered by some to be the oldest board game, as it dates back to Roman times. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it was very popular with English nobility and involved very high gambling stakes.

3 Comments »

3 Comments »

Costa Rica has both lottery games and casino games. Until very recently, the casinos operated on a basis that most charitably would be called Third World. The casinos purportedly operated under the provisions of a 1922 law that indicated which games were legal and which games were illegal. For instance, craps was illegal, but dominos was legal. Blackjack was illegal, but rommy (a variation of the word rummy) was legal. Moreover, roulette gambling was illegal, but if a game was not gambling, it was legal. Slot machines were also illegal. Costa Rica has both lottery games and casino games. Until very recently, the casinos operated on a basis that most charitably would be called Third World. The casinos purportedly operated under the provisions of a 1922 law that indicated which games were legal and which games were illegal. For instance, craps was illegal, but dominos was legal. Blackjack was illegal, but rommy (a variation of the word rummy) was legal. Moreover, roulette gambling was illegal, but if a game was not gambling, it was legal. Slot machines were also illegal.

Not too much notice was given to gaming in Costa Rica before the 1960s. Games were played, but both the operators and the players were Costa Ricans, so it was all a local thing. Then residents of the United States discovered the country. It was close to the United States, and it seemed to be quiet and peaceful. It was the perfect place to retire or to run away if your name was Robert Vesco (a fugitive financier of the Nixon era) or you had the Internal Revenue Service chasing after you. Costa Rica refused to extradite fugitives to the United States. A growing population from the United States was accompanied by growing tourist interest in Costa Rica. The casino activity reached out to foreign “visitors.” In 1963, an ex-dealer from Las Vegas named Shelby McAdams saw an opportunity. He tied a roulette wheel on top of his Nash Rambler car and headed south on the Pan-American Highway. He introduced a new style of casino gaming. And along with a German expatriate named Max Stern, he offered “first class” gaming. McAdams and Stern were accepted by appreciative local residents, and soon others imitated their operations. In the 1970s and 1980s, casino gaming spread to all the major hotels in San Jose, as well as to outlying resort hotels such as the Herradura, Irazu, Cirobici, and Cariari.

The casino operators knew that the patrons wanted blackjack, roulette, and craps games, so they read and reread the 1922 law. Collectively they came up with their solution, and for two decades, they alternatively sought alliances with government officials or fought the efforts of government officials who wanted to read the law another way. I was stunned when I visited most of the gaming facilities in 1989. One casino was named Dominos. Indeed, in the middle of the gaming floor there was a long table and over it was a sign that said “dominos”. Inside the table there was a layout that showed the field, the big six, come, don’t come, pass, don’t pass, and other familiar-looking dice table configurations. The players held two little cubes with white dots on each of their six sides, and they rolled the cubes into the corner of the table. As they did so, they yelled such things as, “Baby needs some new shoes,” “eighter from Decatur,” and “seven come eleven.” I asked the manager just what they were playing. With a straight face, he said, “Dominos.” I looked at the table, and inside the play area there was indeed a stack of dominos. I said, “What are those for?” He said, “Oh, if an investigator or stranger comes in and we think he wants to cause us trouble, we ask the players to put the cubes down and throw the dominos”. As play continued at the “craps,” also known as “dominos” table, a police officer came in. But he was not there to cause trouble, merely to see the manager, who spoke to an assistant. Momentarily the assistant returned with a carton of cigarettes, and the policeman left (with the cigarettes.)

The casinos also offered the game of rommy. Rommy was played with a shoe of six decks. Two cards were dealt to players, and the dealer also took two cards. The players then either “stood” or asked for more cards. If the player’s cards added up to a number closer to twenty-one (without going over twenty-one) than the dealer’s cards, then the player won. All payoffs were on an even-money basis. The casino managers insisted that this was not “blackjack” because blackjack was prohibited by the law. This was “rommy.” There was no blackjack payoff of 5–2; there were payoffs of 10–1 if the player had three sevens and 3–1 if the player had a 5–6–7 straight in the same suit. Rommy was a legal game.

I noticed a small roulette wheel in the back of a casino. I was told that they tried this but the government at the time did not accept it (perhaps they had not given the authorities enough cigarettes?). The roulette game they tried was one called golden ten or observation roulette in Holland and Germany, where it was popular at the time. The wheel was stationary, with its number slats in the middle of a big metal bowl. The dealer would roll the ball slowly so it would make wide ellipses as it rolled to the center. While the ball was slowly moving downward, the player would observe it closely and predict where it would land. With great skill, the predictions could be correct. Hence, argued the casinos, the game was not a gambling game, but a skilled game. The argument worked better in Holland than it did in Costa Rica. The casinos also set up a roulette layout and called the game canasta (a legal game). In this “canasta” game, a single number was drawn out of a basket of Ping-Pong balls (similar to a bingo basket). The number was the winning number for a game played on a roulette layout.

The casino very much wanted to have slot machines, but there was no way they could read them into the 1922 law. In the matter of taxes, the casinos seemed to pay what the government demanded, and that amount was quite flexible and certainly much less than per-table fees stipulated in municipal ordinances.

In 1995, the casinos stopped trying to fight the law. The law was changed, clearly permitting casino games of craps, roulette, and blackjack. Slot machines were also authorized. As of 2000, the number of casinos had been reduced; there were approximately twenty in the country, a dozen being located in the capital city of San Jose. They must be in resort hotels, and the hotel must own the casino.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

Modern gambling came to Connecticut swiftly and almost completely in 1971. A lottery, offtrack betting, and horse-track betting all became legal at the same time. In 1972, dog-racing and jai alai betting were legalized. Only casinos and sports betting remained, and efforts to bring about legalization started in the 1970s. Bills allowing a casino in the depressed community of Bridgeport were introduced in 1981. The measure died in a state legislative committee. Bills were also defeated in 1983 and 1984. The momentum for casinos seemed to die. But Connecticut permitted casino games for charities; they could hold Las Vegas Nights. Connecticut also had Native American tribes. The one organized reservation belonged to the Mashantucket Pequots. They started bingo games and then requested negotiations for casino gaming. After several court battles, the state negotiated to allow the tribe to offer casino table games. In 1992, the tribe asked for slot machines even though they were not permitted in other entities in the state. Without going through the negotiation process, the state agreed to allow the machines if the tribe would give the state 25 percent of the revenues from the machines. The National Indian Gaming Act prohibited state taxation of tribal gaming; therefore, the state and tribe called the “fee” a contribution exchanged for the right to have a monopoly over machine gaming in the state. When a second Native casino opened on a new reservation created by the Mohegans, the Pequots renegotiated the amount of money from the machines that they give the state. In 1999, nearly $300 million went to the state as a result of the agreement. Modern gambling came to Connecticut swiftly and almost completely in 1971. A lottery, offtrack betting, and horse-track betting all became legal at the same time. In 1972, dog-racing and jai alai betting were legalized. Only casinos and sports betting remained, and efforts to bring about legalization started in the 1970s. Bills allowing a casino in the depressed community of Bridgeport were introduced in 1981. The measure died in a state legislative committee. Bills were also defeated in 1983 and 1984. The momentum for casinos seemed to die. But Connecticut permitted casino games for charities; they could hold Las Vegas Nights. Connecticut also had Native American tribes. The one organized reservation belonged to the Mashantucket Pequots. They started bingo games and then requested negotiations for casino gaming. After several court battles, the state negotiated to allow the tribe to offer casino table games. In 1992, the tribe asked for slot machines even though they were not permitted in other entities in the state. Without going through the negotiation process, the state agreed to allow the machines if the tribe would give the state 25 percent of the revenues from the machines. The National Indian Gaming Act prohibited state taxation of tribal gaming; therefore, the state and tribe called the “fee” a contribution exchanged for the right to have a monopoly over machine gaming in the state. When a second Native casino opened on a new reservation created by the Mohegans, the Pequots renegotiated the amount of money from the machines that they give the state. In 1999, nearly $300 million went to the state as a result of the agreement.

The Pequot casino, called Foxwoods, is located near the town of Ledyard. The casino is the largest in the world, with 284,000 square feet of gambling space, a bingo hall, 4,585 machines, and 312 tables. It produces gambling wins of approximately $1 billion a year. The Mohegan Sun casino is managed by Sun International, a company with gambling experience in South Africa and the Bahamas that had earlier acquired and later sold the Desert Inn Casino in Las Vegas. The casino, which is near Uncasville, has a gaming area of 150,000 square feet, 3,000 tables, and 180 tables.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

Anthony Comstock was one of the most prominent reformers in the Victorian era of the later nineteenth century. Other biographies included in this encyclopedia look at the leading gamblers, certainly rogues of the time, but some attention should be given to one who might be truly considered the greatest rogue of all. Comstock did not cheat the innocent, naive, and greedy out of their money. Rather, he purposely cheated society out of personal freedoms, and his vehicle for doing so was government policy and police enforcement powers. His target was sin—all types of sin, especially those of a sexual nature, but also the sins of drinking alcohol and gambling. The impact of the laws he pushed toward passage is still felt today.

On 7 March 1844, Anthony Comstock was born in the small town of New Canaan, Connecticut. He was raised in a very religious family, and he had a disciplined childhood shielded from sinful activities. He came out of this cocoon in 1863, when he joined the 17th Connecticut Company for service in the Civil War. He felt an obligation to serve in place of his brother, who had fallen in battle. The 17th Company saw firefights in South Carolina before it withdrew for passive duty in St. Augustine, Florida. Comstock’s real battles began there. He confronted the foul language and base habits of his fellow soldiers, and he resolved that he would have to change their behaviors. He found the means to change other people in the Army’s Christian Commission and the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). After the war, he moved to New York City and found that once again he was surrounded by sins of all kinds. He actively involved his YMCA comrades in harassing the sinners at every opportunity. He pressured police forces to enforce laws against prostitution and wide-open drinking and gambling.

His politics of enforcement put him in direct opposition to feminist groups. He gained considerable attention in seeking to win a prosecution against Victoria Claffin Woodhall, a free-love advocate who ran for president in 1872. As the result of the following he gained in the battle, he went to Washington, D.C., and secured passage of what became known as the Comstock Obscenity Law. The law prohibited the mailing of any materials with a sexual message of any type. In 1873, he secured a position as the chief inspector of the Postal Service, so the enforcement of the law was in his hands. He went after the job with vigor.

Soon afterwards, he persuaded the New York legislature to charter the New York Society to Suppress Vice. The charter act gave officials of the society “arrest” powers as if they were police officers. Comstock won support from several leading entrepreneurs who wanted to root out the influence of sin over their workforce. Among his supporters was J. P. Morgan. Comstock pushed the New York legislature to act as well. In 1882, state laws were recodified, and all gambling except for horse racing was made illegal. Anthony Comstock went to work against gambling. He harassed the police into some prosecutions against casinos that operated openly in New York City. In this fight he was not successful until 1900 and 1901, when he forced Richard Canfield to close down his city casino, the most glamorous in the country at the time. Comstock was less successful in closing down the Canfield casino in Saratoga.

During Comstock’s later career, he did not emphasize his disdain for gambling, but he pushed where he could. He rivaled, but also allied, Rev. Charles Parkhurst and the Society for the Prevention of Crime in his fights. He was with Parkhurst in 1890 as the reformers persuaded Congress to pass the law banning the use of the U.S. mails by lotteries and other gambling interests. Comstock’s activities were also blended into those of the Progressive movement, and he was aboard the ride that found all gambling, except racing, banned everywhere. Soon after his death, all alcoholic beverages were banned throughout the United States as well.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

The 1970 Organized Crime Control Act authorized the president and Congress to appoint a commission to examine gambling in the United States. The commission was charged with conducting a “comprehensive legal and factual study of gambling” in the United States and all its subdivisions and was instructed to “formulate and propose such changes” in policies and practices as it might “deem appropriate”. At its conclusion, the commission included four U.S. senators (Democrats John McClellan of Arkansas and Howard Cannon of Nevada and Republicans Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania and Bob Taft of Ohio) and four members of the House (Democrats James Hanley of New York and Gladys Spellman of Maryland and Republicans Charles Wiggins of California and Sam Steiger of Arizona). Seven “citizen” members included Commission chairman Charles Morin, a Washington, D.C., attorney; state attorney general Robert List of Nevada; Ethel Allen, a city council member in Philadelphia; Philip Cohen, director of the National Legal Data Center; prosecutor James Coleman of Monmouth County, New Jersey; Joseph Gimma, a New York banker; and professor of economics Charles Phillips of Washington and Lee University. Former federal prosecutor James Ritchie served as the executive director of the commission. The commission had a life of almost three years. The first meetings were in January 1974, and its final report was presented on 15 October 1976.

The commission staff of nearly thirty professionals, twenty student assistants, and twenty-six consultants prepared several dozen research studies. Additionally, the Survey Research Center of the University of Michigan was engaged to conduct the first national survey of gambling behavior ever taken. It also conducted a gaming survey of the Nevada population. The commission also held forty-three days of public hearings in Washington, D.C., as well as in several other cities, including Las Vegas. Testimony was received from 275 law enforcement personnel; persons involved with gambling enterprises, both legal and illegal; and persons representing the general public.

The report presented conclusions suggesting a much more relaxed view of gambling than had been found in earlier federal investigations. Indeed, the commission seemed to be urging the federal government to remove itself from the regulatory process almost entirely. A certain mixed message was given – a recognition that gambling has a downside, but a frustration that legislation seeking to totally outlaw gambling is simply unenforceable. Hence citizens and governments were urged, for the most part, to “roll with the punches”.

The sense of the commission’s feelings is presented in Chairman Morin’s Foreword to the final report: “[We] should carefully reflect on the significance of the fact that a pastime indulged in by two-thirds of the American people, and approved of by perhaps 80 percent of the population, contributes more than any other single enterprise to police corruption…. and to the well-being of the Nation’s criminals…. Most Americans gamble because they like to, and they see nothing wrong with it.” He then highlights a statement from the report: “Contradictory gambling policies and lack of resources combine to make effective gambling law enforcement an impossible task….” He adds, “Not ‘difficult’ – not ‘frustrating’ not even ‘almost impossible’ – but impossible. And why not? How can any law which prohibits what 80 percent of the people approve of be enforced?”(Commission on the Review of the National Policy toward Gambling 1976, ix).

The commission made a firm recommendation that gambling policy be a matter that is determined by the states. Indeed, it urged that Congress enact a statute “that would insure the states’ continued power to regulate gambling” (Commission on the Review of the National Policy toward Gambling 1976, 5). Moreover, the federal government was asked to take care that its regulations and taxing powers not interfere with states’ rights in this area. The commission urged that player winnings from gambling activities not be subject to federal income taxes and that the federal wagering tax and slot machine tax be removed. State authorities were asked to devote law enforcement energies against persons operating gambling enterprises at a “higher” level and to relax enforcement against “low-level” gambling offenses. Prohibitions against public social gambling should be removed. If a state had a substantial amount of illegal gambling, however, the federal government should be authorized to use electronic surveillance techniques not authorized before, and judges were urged to give longer prison terms and more substantial fines to convicted offenders.