Archive for the “E” Category

Encyclopedia: Gambling in America - Letter E

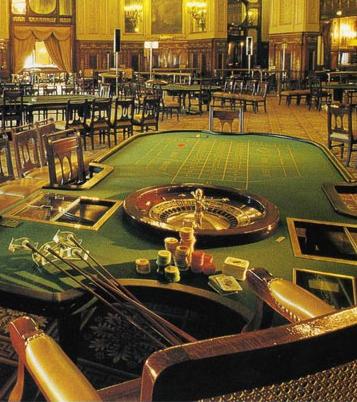

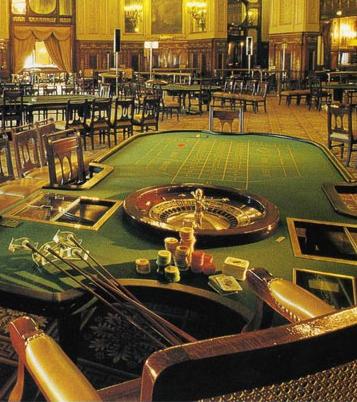

The institution that we call the casino had its origins in central and western European principalities in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was here that governments gave concessions to private entrepreneurs to operate buildings in which games could be legally played in exchange for a part of the revenues secured by the entrepreneurs. Whereas from time immemorial, players had competed against one another in all sorts of private games, here games were structured to pit the player against the casino operators – known as the “house”. These gambling halls were designed to offer playing opportunities to an elite class in an atmosphere that allowed them to enjoy relaxation among their peers. Even though casinos in the United States seek to achieve goals that are primarily financial by offering gaming products to as many persons as possible, the notion of having a European casino often resonates where proponents meet to urge new jurisdictions to legalize casinos.

In some cases, casino advocates actually believe they can somehow duplicate European experiences, but rarely do they meet such goals, for a variety of reasons. If they indeed knew about the way European casinos operate, they would not want any of the experience repeated in casinos they controlled. Other times, they may actually try to establish some of the attributes of these casinos, only to realize later that the attributes are quite adverse to their primary goals—profits, job creation, economic development, or tax generation.

The European casino is offered in campaigns for legalization as an alternative to having a jurisdiction endorse Las Vegas–type casinos. In reality, however, it is the Las Vegas casino that the advocates of new casino legalizations in North America wish to emulate. Among all the casino venues in North America, Las Vegas best delivers on the promise of profits, job creation, economic development, and tax generation. Even though this encyclopedia is devoted to gambling in the Western Hemisphere, the imagery of the European casino is so often used in discussion of casino policy outside of Europe that a descriptive commentary is pertinent here.

In June 1986, I visited the casino that operates within the Kurhaus in Wiesbaden, Germany. In an interview, Su Franken, director of public relations for the casino, was describing a new casino that had opened in an industrial city a few hours away. With a stiff demeanor, he said, “They allow men to come in without ties, they have rows and rows of noisy slot machines, they serve food and drinks at the tables, and they are always so crowded with loud players; it is so awful.” Then with a little smile on his face, he added, “Oh, I wish we could be like that”.

The reality is that, even with the growth in numbers of casino jurisdictions and numbers of facilities, Europe cannot offer casinos such as we are used to in North America – those in Las Vegas and Atlantic City; the Mississippi riverboats; those operated by Canadian provincial governments or by Native American reservations – because a long history of events impedes casino development based upon mass marketing. Actually, the rival casino to which the Wiesbaden manager was referring, the casino at Hohensyburg near Dortmund, was really just a bigger casino, where a separate slot machine room was within the main building as opposed to being in another building altogether. Men usually had to wear ties, but the dress code was relaxed on weekends, and the facility had a nightclub, again in a separate area. It was crowded simply because it was the only casino near a large city, and the local state government did not enforce a rule against local residents’ entering the facility.

The casinos of Europe are very small compared to those in Las Vegas. The biggest casinos number their machines in the hundreds, not the thousands. A casino with more than twenty tables is considered large, whereas one in Las Vegas with twice that number would be a small casino. Even the largest casinos, such as those in Madrid, Saint Vincent (Italy), and Monte Carlo, have gaming floors smaller than the ones found on the boats and barges of the Mississippi River. The revenues of the typical European casino are comparable to those of the small slot machine casinos of Deadwood, South Dakota, or Blackhawk, Colorado. The largest casinos would produce gaming wins similar to those of average Midwestern riverboats.

Baden Baden (Germany) – The most luxurious casino in the world.

Another distinguishing feature of the European casino is that most are local monopoly operations. Where casinos are permitted, a town or region will usually have only one casino. The government often has a critical role in some facet of the operation, either as casino owner (or directly or through a government corporation) or as owner of the building where the casino is located. Where the government does not own the casino, it might as well. Taxes are often so high that the government is the primary party extracting money from the operations. For example, some casinos in Germany pay a 93 percent tax on their gross wins. That means for every 100 marks the players lose to the casino, the government ends up with ninety-three marks. In France the top marginal tax rate is 80 percent; it is 60 percent in Austria and 54 percent in Spain. Nowhere are rates below the top 20–30 percent rates in U.S. jurisdictions (the Nevada rate is less than 7 percent—that is, for each $100 players lose to the casino, the government receives just $7 in casino taxes).

The European casinos typically restrict patron access in several ways. Several will not allow local residents to gamble. They require identification and register patron attendance. They have dress codes. Many permit players to ban themselves from entering the casinos as a protection from their own compulsive gambling behaviors. They also allow the families of players to ban individuals from the casinos. The casinos themselves also may bar compulsive gamblers. (5) The casinos operate with limited hours, usually evening hours. No casino opens its doors twenty-four hours a day. The casinos, as a rule, cannot advertise. If they can, they do so only in limited, passive ways. Credit policies are restrictive. Personal and payroll checks will not be cashed. (8) Alcoholic beverages are also restricted. In many casinos (for instance, all casinos in England), such beverages are not allowed on the gaming floors. Only rarely is the casino permitted to give drinks to players free of charge. (Other free favors such as meals or hotel accommodations or even local transportation are also quite rare.)

The clientele of the European casino is generally from the local region. Few of the casinos rely upon international visitors. Moreover, very few have facilities for overnight visitors, although several are located in hotels owned by other parties. The casinos feature table games, and where slot machines are permitted, they are typically found in separate rooms or even separate buildings. The employees at the casinos are usually expected to spend their entire careers at a single location. The employees are almost always local nationals.

There are myriad reasons why the European casino establishment has remained in the past, while modern casino development occurred in the United States, specifically in Las Vegas. First, Europe is a continent with many national boundaries. The future may see more and more economic and even political integration, but national separateness has been strong and will remain as a factor retarding casino development. The European Union has, at least at its initial stage of decision making, decided to allow casino policy to remain under the jurisdiction of its individual member states. Although a central congress may decree that all European states must standardize other products, usually following the most widely attainable and profitable standards, there will be no decrees that the entire continent should follow the most liberal casino laws. Each country retains sovereignty in this area.

Language and religious differences separate the various nations of Europe. No European congress can decree away these differences. National rules of casino operation have emphasized that entrepreneurs and employees be local residents. Such rules remain in place in most jurisdictions. In the past, movement of capital has been restricted among the states, making the possibilities of accumulating large investments for large resort facilities and for large promotional budgets difficult. Additionally, it was difficult for players to move their gaming patronage across borders, as they also would have to be able to move capital with that patronage. Advertisement restrictions also tied casino entrepreneurs to local markets. These small local markets never beckoned as attractive opportunities for foreign investors even when they could move funds.

Second, employment practices have not fostered the kind of cross-germination that is present in the North American casino industries. Typically, the employees of European casinos are local residents, and they are expected to stay with one casino property for an entire career. Promotions come from within. The work group is very personal in its interrelationships. The work group is also unionized and derives much of its wage base from tips given by players at traditional table games. The employment force is simply not a source for innovative ideas.

Third, as almost all of the casinos are monopoly businesses, the industry has had little incentive to develop competitive energies that could be translated into innovations. Also, the entrepreneurs have not been situated to take advantage of the forces of synergy, which are quite obvious in the Las Vegas and the U.S. gaming industry.

Fourth, the basic political philosophy that dominates government policymaking in Europe has its roots in notions of collective responsibility. Americans threw off the yoke of feudalism and its class system of noblesse oblige when the first boats of immigrants reached its Atlantic shores in the seventeenth century. The colonies fostered a spirit of individualism. Conversely, a spirit of feudalism persists in European politics. Remnants of monarchism remain, as the state has substituted official action for what was previously upper-class obligation. Socialist policies now ensure that the working classes will have their basic needs guaranteed. The government is the protector as far as personal welfare is concerned, and those protecting personal welfare (that is, the government officials) also are expected to guide personal behavior, even to the point of protecting people from their own weaknesses.

In the United States, and especially in the American West, the expectation was that people would control their own behaviors; such was not the case in Europe. In Europe, but not in the United States, viable Socialist parties developed. Coincidentally, Christian parties also developed. They too fostered notions that the state was a guardian of public morals. Christian parties saw casinos as anathema to the public welfare and permitted their existence only if they were small and restricted. Socialists also saw casinos as exploiting-bourgeois enterprises that had to be out-of-bounds for working-class people.

Fifth, and perhaps the overriding force against commercial development of casinos, there has been an almost perpetual presence of wartime activity in Europe over the past three centuries. The many borders of Europe have caused a constant flow of national jealousies, alliances, and realignments, all of which contributed to one war after another. Often the wars engulfed the entire continent: the Napoleonic wars, the Franco-Prussian wars, and World Wars I and II. A modern casino industry cannot flourish amid wartime activity. Casinos need a free flow of people as customers, and people cannot move freely during wartime. Casinos need markets of prosperous people, but personal prosperity is disrupted for the masses during wartime. Wartime destruction consumes the resources of society. Moreover, a society does not allow its capital resources to be expended on leisure activities when the troops in the field need armaments. And wars change boundaries, governments, and rules. Casinos need stability in the economy and in political policy in order to grow; Europe has lacked stability over the last three centuries.

The United States has benefited from not being a war battlefield for over a century. Following World War II, the new industrial giant of the world accepted an obligation to help European countries rebuild their industrial and commercial bases. The Marshall Fund was created to infuse U.S. capital into European redevelopment. The Marshall Fund could have been a vehicle for infusing the individualistic American spirit of capitalism into European commercial policy as well. The fund stipulated, however, that the new and revitalized businesses of Europe had to be controlled by Europeans. U.S. entrepreneurs were not allowed into fund-supported businesses. The fund actually supported the reopening of a casino at Travemunde, Germany. But the policy of the U.S. government in not allowing Americans to directly participate in the commercial enterprise of rebuilding Europe blocked U.S. casino operators from legitimately entering Europe with the modern spirit they were utilizing in Las Vegas gambling establishments. On the other hand, less than fully legitimate Americans sought to bring slot machines to the continent. They were rooted out, however, and as these “operators” were deported, the image of the slot machine as a “gangster’s device” became firmly rooted into casino thinking in Europe.

The impacts of these many forces are felt today even though the existence of the forces is not as strong. There is much expansion of casino gambling in Europe. It is generally an expansion in the number of facilities, however, not in the size or scope of the facilities. Each of the former Eastern Bloc countries now has a casino industry, but restrictions on size and the manner of operations are severe, as are tax requirements. France authorized slot machines for its casinos for the first time in 1988. But a decade later, its largest casinos were producing revenues less than those of a typical Midwest riverboat, revenues measured in the tens of millions of dollars—nowhere near the hundreds of millions won by the largest Las Vegas and Atlantic City casinos. In Spain, casino revenues have been flat as the industry begs the government for tax relief. Austria has developed a megacasino at Baden bi Vien, but it would be almost unnoticeable on the Las Vegas Strip. Casinos Austria and Casinos Holland, two quasi-public organizations, are viewed as two of the leading casino entrepreneurs of the continent. But both derive much of their revenue from operations of casinos either on the sea or in Canada. Twenty Las Vegas and a dozen Native American properties exceed the revenues of the leading casinos in Germany.

The European casinos have a style that would be welcomed by many North American patrons. In achieving that style, however, the casinos must forfeit what most entrepreneurs, governments, and citizens want from casinos—profits, jobs, economic development, and tax generation.

No Comments »

No Comments »

The essence of gambling is economics – gambling involves money. Money is put at risk, and money is won or lost. Money goes into the coffers of organizations such as racetracks, casinos, lotteries, or charities, and that money is redistributed in taxes or public funds, profits, wages, and various supplies. The money of gambling can help economies of local communities and regions grow, but gambling operations can also cause money to be drawn out of communities. The existence of gambling represents an opportunity to express personal freedoms, and these have values, although they are not easy to measure in a precise manner. On the other hand, gambling can also impose costs upon societies because of problem behaviors of persons who cannot control gambling impulses.

Gambling enterprises, specifically casino resorts and racetrack operations, involve major capital investments. These may come through expenditures of individual entrepreneurs, sale of stock at equity exchange markets (e.g., the New York Stock Exchange), bond issues, or other borrowing mechanisms. Gambling enterprises are subject to a wide range of competitive forces. Participants in each form of gambling compete against one another, but they also compete against other entertainment providers as well as all other services and products that can be purchased with the consumers’ expendable dollars.

The vast array of economic attributes tied to gambling has led to many studies that focus upon gambling economics. Most concentrate upon positive sides of the gambling equation, and they tend to overlook a very basic fact: Gambling revenues must come out of the pockets of players. In my lectures on gambling, I like to point out that Las Vegas was the fastest-growing city in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s, with the greatest job growth and wage growth. Yet Las Vegas is in a desert – it does not have trees. On the other hand, the wooded areas of the United States have suffered economic declines – albeit during a prosperous period for the general economy. The point is, quite simply, that “money does not grow on trees.” A large casino may generate great revenues that can be translated into many jobs; however, those revenues do not fall out of the air. They come from people’s pockets. I also like the story of the man whose life is falling apart. As he is driving to church, he sees a sign that says “Win the Lotto, and Change Your Life”. In church he prays that he will win. He hears the voice of God telling him, “My Son, you have been good; you shall win the lottery.” Convinced his problems are over, the man is much relieved. But he does not win the lottery. The next week, instead of praying to God, he is angry and asks God why He lied, why He has forsaken him. God replies, “Yes, my son, I understand your anger, because I did promise. But my son, you have to meet me half way. You have to buy a ticket”. All the money that is discussed in studies of the economics of gambling is money that has to come out of people’s pockets. Unless individuals “buy the ticket,” there is no gambling phenomenon – no lotteries, no racetracks, and no casinos. The formula for understanding gambling economics is not difficult. It can be expressed in but a few words: It involves where the money comes from and where the money goes. In the second section of this entry, we will return to this basic formula. First we will look at the revenues in gambling.

Gambling Revenues

In 1998, gambling players spent (another way of saying “lost”) $54.4 billion on legal gambling products in the United States (this is called the gambling “hold”) (Christiansen 1999). The $54.4 billion represents the money that gambling enterprises retained after players wagered $677.4 billion dollars (this is called the gambling “handle”). In other words, casinos, lotteries, and tracks kept 8 percent of the money that is played. The greatest share of these players’ losses was in casino facilities of one kind or another, followed by purchases of lottery tickets.

Since the statistics of all legal gambling began to be compiled in 1982, the gambling revenues have increased an average of 10.4 percent every year. Overall, the growth in revenues has been more than 530 percent, compared with a 150 percent increase in the Gross Domestic Product (Christiansen 1999). The gambling growth has been seen in all areas, although only minimally in the pari-mutuel sector of gambling. Much of the growth is due to the fact that new jurisdictions have legalized forms of gambling and that new gambling facilities have been established.

If all gambling were conducted in one enterprise, the business would be among the ten largest corporations in the country. Gambling revenues in the United States represent the largest share of entertainment expenditures. Indeed, the revenues surpass those of all live concerts; sales of recorded music; movie revenues, theater and video; and revenues for attendance at all major professional sporting events combined! The revenues surpass the sales of cigarettes by 13 percent. The gambling revenues approach 1 percent of the personal incomes of all Americans.

In 1998, the commercial casinos attracted 161.3 million visits from customers representing 29 percent of the households (or 28.8 million households) in the United States. The average visitor made 5.6 trips to casinos. The visitors spent an average of $123 during each of those visits. Visits to venues in Las Vegas, Atlantic City, and other resort gambling areas will be for days in length, accounting for larger expenditures, whereas those visiting casino boats usually confine their gambling to two or three hours of time; many boats impose time limits. A typical boat visitor will lose $50–$60 per visit. With approximately 200 million adults in the country, each spends an average of $100 per year in commercial casinos, but $147 in all casinos, including those operated by Native Americans and charities.

A higher percentage of households participates in lottery games – 54 percent (or 53.5 million households). They play on a regular basis, buying tickets each week; hence they do not lose as much to this form of gambling at a single time. The average American adult spends $84 a year on lottery tickets or video lottery play.

Approximately 11 percent of the households participate in bingo games and 8 percent in racetrack betting. Considering all the forms of legal gambling, the average adult spends (loses) $272 on gambling each year. When that amount is spread over the entire population of 270 million, the per capita expenditure is $200 (Christiansen 1999).

Employment and Gambling

Employment is considered one of the leading benefits of gambling enterprise. Proponents of gambling initiatives usually make “job creation” a central issue in their campaigns. Gambling provides jobs. There is no doubt about that. Estimates suggest that well over 600,000 people are employed by legal gambling enterprises in the United States. Critics of gaming suggest, however, that specific gambling interests may not provide net job gains for communities, as gambling employees may be people who simply moved from other jobs. Moreover, gamblers themselves may lose jobs because of their behavior, and their gambling losses may also result in a loss of purchasing power in a community, leading others to unemployment. Critics also suggest that gambling jobs are not necessarily “good” in that they may offer low salaries, low job security, and poor working conditions. Gambling proponents counter these claims and add that jobs produced lead to indirect jobs through economic multipliers.

The different gambling sectors produce different job circumstances. Casinos are labor-intense organization. Racing provides fewer jobs at track locations but generates many direct jobs in the agriculture sector on horse breeding farms. Modern lotteries in North America are not job providers in a major sense. Government bureaucracies increase employment; however, a lottery distribution system using existing retailers adds few jobs to society.

The casino and racing sectors provide jobs in North America in the same manner as they do elsewhere. Lotteries, however, are quite different.

In Europe as well as in traditional societies, poor people and handicapped people find employment through selling tickets. For instance, over 10,000 blind and handicapped persons support themselves through selling tickets in Spain. They are able to have incomes of about $30,000 a year through their activities. Moreover, administration of a special lottery organization is staffed by the handicapped, and all of the proceeds from ticket sales are designated for programs for the handicapped. In many poorer countries, persons who could not otherwise secure employment buy discounted lottery tickets on consignment and resell them in order to support themselves and their families. In Guatemala City, Guatemala, and Teguicalpa, Honduras, the lottery sales force gathers in squares near cathedrals or government buildings and creates market atmospheres with its activities. The lotteries in these countries produce revenues for charities. In the United States, Canada, and other modern lottery venues, the sale of tickets is directed almost exclusively to provide general revenues for government activities. Therefore, the goal of the lottery organization is to maximize profits through efficient procedures. Sales are coordinated through banks and major retail outlets, which conduct lottery business along with other product sales. As the tickets are simply added to other purchases made by the gamblers, there is little if any employment gain through the activity.

Big corporations usually control the lottery retailers. In many cases, however, they are small businesses that may be aided considerably by volumes of ticket sales. Ticket sales may provide them with margins of profits enabling their businesses to compete with larger merchants. Video lottery machines (gambling machines) also provide revenues that allow bars and taverns to remain competitive with other “entertainment” venues and, hence, remain as employers in society.

According to industry reports, pari-mutuel interests that run horse and dog tracks as well as jai alai frontons employ about 150,000 workers in the United States. Less than 2 percent of this number are working at the nation’s ten frontons. 30,000 work at dog tracks and 119,000 at horse tracks. The numbers for tracks include 36,300 employed at track operations, 52,000 as maintenance workers, and 30,800 in the breeding industry (National Gambling Impact Study Commission 1999, 2.11–2.12).

Casinos are responsible for most of the gambling employees. A report of the American Gaming Association showed that in 1999 casinos in the United States directly employed almost 400,000.

The Nevada gaming industry indicates that the tourism in Nevada in 1998 employed 307,500, with 182,621 directly in gaming. In that same year, the state led the nation in job growth. Unemployment in Las Vegas was a very low 2.8 percent. Indirect employment led analysts to observe that in 1998 casinos were responsible for 60 percent of the employment in the state. Each of the casino jobs in Nevada leads to the employment of 1.7 persons in all—that is, an extra 0.7 employee (or seven employees for every ten casino employees). This multiplier factor (1.7) is considered rather low. It is low because Nevada is not a manufacturing state. In fact, with a 3-percent manufacturing sector, the state manufactures less per person than any other state. As the state produces few products, almost the entire casino purchasing activity is directed to imported goods and, accordingly, not to goods produced by Nevada workers.

New Jersey casinos employ approximately 50,000 workers. The industry claims that this employment creates employment of 48,000 workers through purchasing activities of casinos and casino employees. In 1998, the 50,000 jobs produced a payroll of $1 billion, or $20,000 per job. Many of the jobs are not full time. Although the employment in Atlantic City gambling halls is extensive (averaging over 4,000 per casino), the casinos have not solved the problems of poverty and unemployment in the community, a city of 38,000. The population of Atlantic City has continually declined since the introduction of casinos in 1978, and its unemployment rate was 12.7 percent in 1998, a time when the national average and state of New Jersey average were approximately 4 percent.

Mississippi casinos employed 32,000 in 1998. As the casinos of the state were established in the 1990s, the effects of construction employment have been noticeable. For instance, from 1990 to 1995 an additional 1,300 construction jobs existed in Biloxi, one of the state’s casino centers. The jobs persisted through the end of the century; however, construction jobs must be tied to specific projects, and when the projects are finished, the jobs are finished. Although Mississippi experienced a boom with the introduction of casinos in 1992, the new employment witnessed in the state did not alter unemployment rates to a degree that was any different than that for the entire country. The 1990s were prosperous, and casino communities in the state experienced the same prosperity felt by noncasino communities.

A similar phenomenon has taken place in the Native American community. There, scores of casinos have generated about 100,000 jobs. Most of the jobs, however, are found in casinos on very small reservations. Overall Native Americans still experience the worst economy of any subsector of the U.S. population, with unemployment rates over 50 percent. Lots of people, mostly non-Native Americans, have obtained jobs in casinos, and small tribes have became extremely wealthy, but generally the Native American community has not “cashed-in”.

Other sectors of the gambling industry have not caused job creation. The National Gambling Impact Study Commission reported that there was no evidence whatsoever that convenience store gambling (machine gambling) created any jobs. Charity gambling has produced considerable funding for myriad projects, but it has not produced jobs either (National Gambling Impact Study Commission 1999, chap. 2).

A study of jobs produced by the onset of riverboat casino gambling in Illinois found that the multiplier of each job was less than one, but still more than zero. That meant that most of the new jobs were only shifted away from other enterprises, and the vacant jobs were not filled in all cases. Indeed, a multiplier of approximately 0.2 resulted as the casinos added 10,000 jobs, but the numbers employed overall increased by only 2,000. The unfilled vacant jobs were possibly not filled because the casinos extracted purchasing power away from the residential populations. Casino jobs can also cause undesired impacts for a community by depriving other businesses of workers. Atlantic City casinos drew many new employees from local school districts and local police forces. In free markets, people can make job and career choices on their own, and such job shifts indicate that some people may see casino jobs as better than other available jobs (Grinols and Omorov 1996, 19).

The industry jobs have been both praised and criticized. The positions run the gamut, from stable hand to chief executive, from minimum wage without benefits to seven-figure positions with golden parachutes. A stable hand working with horses may be residing in very substandard housing conditions, perhaps ever sharing quarters with the animals he or she cares for. The largest number of “good” positions is found in commercial casinos. The bulk of these jobs are unionized and carry very good fringe benefit packages, including full health coverage for families of workers. Dealer positions, for the most part, are not unionized, although they do have good fringe benefits. The dealers usually make low salaries, but they share tips. Where tips are not good (or not permitted, as in Quebec), salaries are higher. The best tip situations are found in Atlantic City and on the Las Vegas Strip. A typical dealer at a casino such as Caesars might expect an additional $50,000 a year in tips.

Working conditions in gambling facilities are often not the best. There is high job turnover due to job dissatisfaction and also to policies that sometimes allow firing at will. Traditionally, people were hired in Las Vegas casinos through friendship networks; however, this practice is now less pervasive, as the industry has grown considerably and it is more a “buyers,” that is, an employees’, market. Nonetheless, other adverse conditions surround casino employment. For years the casino atmosphere was one that was dominated by “male” values. Women employees were often placed into situations where they were degraded. This behavior came from fellow employees as well as from customers. It is unacceptable behavior today, yet in some ways it is still tolerated in the casino atmosphere. That atmosphere also has downsides from a health standpoint, as most casinos permit open smoking—and many players smoke—as well as drinking. Casinos can be very loud, and of course, employees work shifts over a twenty-four-hour schedule.

Most workers in the United States have indicated in surveys that job security and salaries are no longer the leading motivators, but rather that factors such as “ability to get ahead,” “recognition for work accomplished,” and “having responsibility” are more important. A survey of casino dealers found, however, that they desired security and financial compensation over the other factors. This is an indication of the insecurity that persists among the workforce (Darder 1991).

No Comments »

No Comments »

Does gambling help the economy? This question has been asked over and over for generations. Economic scholars such as Paul Samuelson have suggested that since gambling produces no tangible product or required service, it is merely a “sterile” transfer of money. Therefore the energies (and all costs) expended in the activity represent unneeded costs to society. Further, he points out that gambling activity creates “inequality and instability of incomes” (Samuelson 1976, 425).

On the other hand, a myriad of economic impact studies have concluded that gambling produces jobs, purchasing activity, profits, and tax revenues. Invariably, these studies have been designed by, or sponsored by, representatives of the gambling industry. For instance, the Midwest Hospitality Advisors, on behalf of Sodak Gaming Suppliers, Inc., conducted an impact study of Native American casino gaming. Sodak had an exclusive arrangement to distribute International Gaming Technologies (IGT) slot machines to Native American gaming facilities in the United States. The report was “based upon information obtained from direct interviews with each of the Indian gaming operations in the state, as well as figures provided by various state agencies pertaining to issues such as unemployment compensation and human services”.

The study indicated that the Minnesota casinos had 4,700 slot machines and 260 blackjack tables in 1991. Employment of 5,700 people generated $78.227 million in wages, which in turn yielded $11.8 million in social security and Medicare payments, $4.7 million in federal withholding, and $1.76 million in state income taxes. The casinos spent over $40 million annually on purchases of goods from in-state suppliers. Net revenues for the tribes were devoted to community grants as well as to payments to members, health care, housing, and infrastructure. The report indicated that as many as 90 percent of the gamers in individual casinos were from outside Minnesota; however, there was no indication of the overall residency of the state’s gamblers.

The American Gaming Association (AGA) ignores the question of where the money comes from as it reports that “gaming is a significant contributor to economic growth and diversification within each of the states where it operates” (Cohn and Wolfe 1999, 7). An AGA survey talks of the jobs, tax revenues, and purchasing of casino properties in 1998: a total of 325,000 jobs, $2.5 billion in state and local taxes, construction and purchasing leading to 450,000 more jobs, and $58 million in charitable contributions for employees of casinos. The report indicates that the “typical casino customer” has a significantly higher income than the average American, with 73 percent setting budgets before they gamble (there was no indication about how many of these kept their budgets), making them a “disciplined” group. The report made no attempt to see if the players were local residents or not.

Likewise, another study sponsored by IGT and conducted by Northwestern University economist Michael Evans found that “on balance, all of the state and local economies that have permitted casino gaming have improved their economic performance” (The Evans Group 1996, 1–1). Evans found that in 1995, casinos had employed 337,000 people directly, with 328,000 additional jobs “generated by the expenditures in casino gambling”. State and local taxes from casinos amounted to $2 billion in 1995, and casinos yielded $5.9 billion in federal taxes. Yet Evans did not consider that the money for gambling came from anywhere, or that the money could have been spent elsewhere if it were not spent in casino operations, or that if spent elsewhere, it would also generate jobs and taxes. The studies by industry-sponsored groups also neglect the notion that there could be economic costs as a result of externalities to casino operations – namely, as a result of the increased presence of compulsive gambling behaviors and some criminal activity. Evans brushed aside the possibilities with a comment that “the sociological issues that are sometimes associated with gaming, such as the rise in pathological gamblers who ‘bet the rent money’ at the casinos, are outside the scope of this study. Nonetheless, it seems appropriate to remark at this juncture that occasional and anecdotal evidence does not prove anything”.

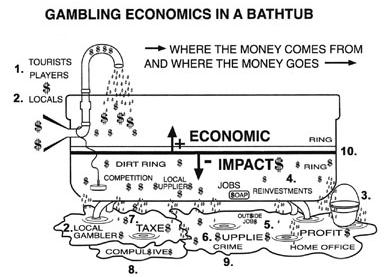

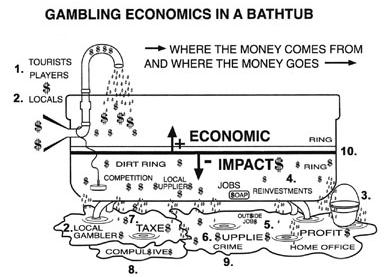

1–2. Source of Gambling Funds; 3. Profits to outside owners; 4. Profits reinvested in casino location; 5. Jobs; 6. Purchase of supplies; 7. Taxes; 8. The social cost of pathological gambling; 9. The costs of gambling-related crime; 10. The dirt ring – we don’t see it if the water level is rising.

Whatever is produced by a gambling enterprise does not come out of thin air; it comes from somewhere, and that “where” must be identified if we are to know the economic impacts of gambling operations. The impact studies commissioned by the gambling industry fall short.

So what is the impact of gambling activity upon an economy? This is a difficult question to answer, as the answer must contain many facets, and the answer must vary according to the kind of gambling in question as well as the location of the gambling activity. Although the question for specific gambling activity poses difficulties, the model necessary for finding the answers to the question is actually quite simple. It is an input-output model. Two basic questions are asked: (1) Where does the money come from? and Where does the money go? The model can be represented by a graphic display of a bathtub.

Water comes into a bathtub, and water runs out of a bathtub. If the water comes in at a higher rate than it leaves the tub, the water level rises; if the water comes in at a slower rate than it leaves, the water level is lowered. An economy attracts money from gambling activities. An economy discards money because of gambling activity. Money comes and money goes. If, as a result of the presence of a legalized gambling activity, more money comes into an economy than leaves the economy, there is a positive monetary effect because of the gambling activity. The level of wealth in the economy rises. If more money leaves than comes in, however, then there is a negative impact from the presence of casino gambling. Several factors must be considered in what I will call the Bathtub Gambling Economics Model. We must recognize the source of the money that is gambled by players and lost to gambling enterprises, and we must consider how the gambling enterprise spends the money it wins from players.

Factors in the Bathtub Gambling Economics Model

Tourist players: Are players/persons from outside the local economic region (defined geographically) – and are they persons who would not otherwise be spending money in the region if gambling activities were absent? A tourist’s spending brings dollars into the bathtub unless they otherwise would have spent the money in the region.

Local players: Are the players from the local regional economic area? If so, does the presence of gambling activities in the region preclude their travel outside the region in order to participate in gambling activities elsewhere? If they are locals who would not otherwise be spending money outside the region, their gambling money cannot be considered money added to the bathtub.

Additional player questions: Are the players affluent or people of little means? Are the players persons who are enjoying gambling recreation in a controlled manner, or are they playing out of control and subject to pathologies and compulsions?

Profits: Are the profits from the operations staying within the economic region, are they going to owners (whether commercial, tribal, or governments) who reside outside the economic region, or are they reinvested by the owners in projects that are outside of the region?

Reinvestments: Are profits reinvested within the economic region? Are gambling facilities expanded with the use of profit moneys? Are facilities allowed to be expanded?

Jobs: Are the employees of the gambling operations persons who live within the economic region? Are the casino executives of the companies who operate (or own) the facilities local residents?

Supplies: Does the gambling facility purchase its nonlabor supplies – gambling equipment (machines, dice, lottery and bingo paper), furniture, food, hotel supplies – from within the economic region?

Taxes: Does the facility pay taxes? Are profits leading to excessive federal income taxes? Are gambling taxes moderate or severe? Do the gambling taxes leave the economic region? Does the government return a portion of the gambling taxes to the region? How expensive are infrastructure and regulatory efforts that are required because of the presence of gambling that would not otherwise be required? Do the gambling taxes represent a transfer of funds between different economic strata of society?

Pathological gambling compulsive or problem gambling): How much pathological gambling is generated because of the presence of the gambling facility in the economic region? What percentage of local residents have become pathological gamblers? What does this cost the society – in lost work, in social services, in criminal justice costs?

Crime: In addition to costs caused by pathological gamblers, how much other crime is generated by gamblers because of the presence of a gambling facility? How much of this crime occurs within the economic region, and what is the cost of this crime for the people who live in the economic region?

The construction factor: If a gambling facility is a large capital investment, the infusion of construction money will represent a positive contribution to the economic region at an initial point. The investors must be reimbursed for the construction financing with repayments and interest over time, however. The long-range extractions of money from a region will more than balance the temporary infusions of money into a region. An application of the model must recognize that the incomes eventually produce outgoes. The examples that follow therefore ignore the construction factor—although more refined examples may see it as positive for initial years and negative thereafter.

Some Descriptive Applications of the Model

The Las Vegas Bathtub Model

The Las Vegas economy has witnessed phenomenal growth in the past few years. This has occurred even in the face of competition from around the nation and world, as more and more locations have casinos and casino gambling products. As of the end of 2000, the Las Vegas economy was strong because the overwhelming amount of gambling money (as much as 90 percent) brought to the casinos came from visitors. According to 1999 information from the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, visitors stay in Las Vegas an average of four days, spending much money outside of the casino areas. Las Vegas has money leakage as well. State taxes are very low, however, and much of the profits remains, as owners are local. Or if not, they see great advantages in reinvesting profits in expanded facilities in Las Vegas. The costs of crime and compulsive gambling associated with gambling are probably major; however, many of these costs are transferred to other economies, as most problem players return to homes located in other economic areas. Las Vegas is not a manufacturing or an agricultural region, so most of the purchases (except for gambling supplies) result in leakage to other economies. Gambling locations in Las Vegas such as bars, 7-11 stores, and grocery stores represent very faulty bathtubs—bathtubs with great leakage.

Other Jurisdictions in the United States

Atlantic City’s casino bathtub functions appropriately, as most of the gamblers are from outside the local area. Players are mostly “day-trippers”, however, who do not spend moneys outside the casinos. Most purchases, as with those in Las Vegas, result in leakage for the economy. Like those in Las Vegas, state gaming taxes are reasonably low. Other taxes, however, are high.

Most other U.S. jurisdictions do not have well-functioning bathtubs, because most offer gambling products, for the most part, to local players. Native American casinos may help local economies because they do not pay gambling excise taxes or federal income taxes on gambling wins, as they are wholly owned by tribal governments who keep profits (which are in the form tribal taxes) in the local economies.

Two Empirical Applications of the Model Illinois Riverboats.

In 1995, I participated in gathering research on the economic impacts of casino gambling in the state of Illinois (Thompson and Gazel 1996). Illinois has licensed ten riverboat operations in ten locations of the state. The locations were picked because they were on navigable waters and also because the locations had suffered economic declines. We interviewed 785 players at five of the locations. We also gathered information about the general revenue production of the casinos and the spending patterns of the casinos—wages, supplies, taxes, and residual profits. The casinos were owned by corporations; most of them were based outside of the state, and none of them were based in the particular casino communities.

The focus of our attention was the local areas within thirty-five miles of the casino sites. The data were analyzed collectively, that is, for all the local areas together.

In 1995, the casinos generated revenues of just over $1.3 billion. Our survey indicated that 57.9 percent of the revenues came from the local area, from persons who lived within thirty-five miles of the casinos. From our survey we determined, however, that 30 percent of these local gamblers would have gambled in another casino location if a casino had not been available close to their home.

Therefore, in a sense, their gambling revenue represented an influx of money to the area. That is, the casino blocked money that would otherwise leave the area. We considered a part of the local gambling money to be nonlocal money, in other words, visitor revenue. On the other side of the coin, as a result of our surveys, we considered that 22 percent of the visitors’ spending was really local moneys. Many of the nonlocal gamblers indicated that they would have come to the area and spent money (lodging, food, etc.), even if there were no casino in the area.

By interpolating the income for one casino from the total data collected, we envision a casino with $120 million in revenue. The share of these revenues that came from within the thirty-five-mile economic area (after adjustments for the 30 percent retained from other casino jurisdictions) equaled $60 million. In other words, we can represent this as local money lost to the casino. The question then is, how much of the money from the casino revenues of $120 million was retained in the thirty-five-mile area.

The direct economic impact was negative $8.367 million (that is, $60 million of revenues came from the local thirty-five-mile area, but only $51,632,200 of the spending was locally retained). A direct economic loss for the area of $8,367,800 may be multiplied by approximately two, as the money lost would otherwise have been able to circulate two times before leaving the area economy. The direct and indirect economic losses due to the presence of the gambling casino therefore equaled $16,735,600.

Added to these economic losses are additional losses due to externalities of social maladies. For each local area, there will be an increase in problem and pathological gambling, and there will also be an increase in crime due to the introduction of casino gambling. The presence of casino gambling, according to one national study (Grinols and Omorov 1996), added to the other social burdens of society, such as taxes, per-adult costs of $19.63 due to extra criminal activity and criminal justice system costs due to related crime. The National Gambling Impact Study Commission found that the introduction of gambling to a local area doubled the amount of problem and pathological gambling (National Gambling Impact Study Commission 1999, 4–4). Our studies of costs due to compulsive gambling find adults having to pay an extra $56.70 each because of extra pathological gamblers (0.9 percent of the population) and an extra $44.10 each because of extra problem gamblers (2 percent of the population). This additional $120.43 per adult translates into an extra loss of $12,043,000 (or $24,086,000 with a multiplier of two) for an economic area of 100,000 adults when the first casino comes to town.

The players’ interviews indicated that 37.2 percent were from the thirty-five-mile area surrounding the casino. Of their $44.64 million in gambling revenues, 20 percent is money that would otherwise be gambled elsewhere. On the other hand, 10 percent of the $75.36 million gambled by “outsiders” would have otherwise come to the area in other expenses by these players. Hence we consider that $43.248 million of the losses are from the local area and $76.752 million comes from the “outside”.

The positive local area economic impacts of Native American casinos in Wisconsin contrast to the negative impacts in Illinois for several reasons. The Illinois casinos are purposely put into urban areas as a matter of state policy. As a result, a higher portion of gamers are local residents; therefore, fewer dollars are drawn into the area. The urban settings also exacerbate social problems, as the negative social costs are retained in the areas. The two major factors distinguishing the positive from negative impacts are the fact that the Native casinos do not pay taxes to outside governments and the fact that the ownership of the casinos by local tribes keeps all the net profits (less management fees) in the local areas.

Other Forms of Gambling

The economic model can be applied to all forms of gambling. Other findings may arise from studies, however. For instance, for horse-race betting, there would have to be a realization that commercial benefits of racing are spun off to a horse breeding industry. Today those benefits could be seen merely in terms of dollars. In the past, however, those benefits were seen in terms of a valued national resource. Because breeding was encouraged, the nation’s stock of horses was improved in both quality and quantity, and that stock was a major military resource in times of war. Even though the Islamic religion condemned gambling as a whole, exceptions were made for horse-race betting precisely because it would provide incentives for “improving the breed.” Another consideration affecting race betting is the source of funds that are put into play by widely dispersed offtrack betting facilities, and then how those funds are distributed. The employment benefits of racetracks are also more difficult to put into a geographical context, as many employees work for stables and horse owners whose operations are far from the tracks.

Lotteries also draw sales from a wide geographic area. Funds are all given to government programs; however, the funds are often designated for special programs. The redistribution effects are difficult to trace and are dependent on the type of programs supported. When casino taxes are earmarked, the same problem exists; however, a casino tax will be much less than the government’s share of lottery revenues. Lotteries do not provide the same employment benefits for local communities as are provided by casinos, as they are not as labor intensive. Benefits from sales tend to go to established merchants, often large grocery chains, in the lottery jurisdiction.

National lottery games, such as Lotto America, only further complicate the economic formulas. Such is also the case with Internet gambling. For race betting and lotteries, there is very little activity by nonresident players.

What Do Negative Gambling Economic Impacts Mean for a Local Community?

Negative direct costs, imposed on an area by the presence of a casino facility, simply mean there can be no economic gains for the economy. There can be no job gains, only job losses. Purchasing power is lost in the community; local residents play the gambling dollars, and those residents do not have funds for other activities. Our survey of Wisconsin players found that 10 percent would have spent their gambling money on grocery store items if they had not visited the casino. One-fourth indicated they would have spent the money on clothing and household goods. Additionally, there can be no real government revenue gains, except at a very high cost imposed upon local residents in severely reduced purchasing powers and high social costs. Negative impacts simply mean the facilities are economically bad for an area.

No Comments »

No Comments »

|