Archive for the “F” Category

Encyclopedia: Gambling in America - Letter F

Florida has the third-most-profitable lottery and the third-most-active pari-mutuel enterprise in the United States. The pari-mutuel industry features horse racing, dog racing, and jai alai games. The state has had a long history with underground gambling and with elements of organized crime that ran gambling operations throughout the country and in many other places as well. Florida has the third-most-profitable lottery and the third-most-active pari-mutuel enterprise in the United States. The pari-mutuel industry features horse racing, dog racing, and jai alai games. The state has had a long history with underground gambling and with elements of organized crime that ran gambling operations throughout the country and in many other places as well.

Miami had been designated in the 1930s as an “open city” by the Mob. That meant all organized crime families were welcome to live in Miami and to conduct their business operations, whether they involved sex, drugs, or gambling. During the 1940s, illegal casinos flourished in the southern part of Florida. Meyer Lansky made Miami Beach his headquarters for much of his adult life.

From there he guided his activities in Cuba, the Caribbean, and Las Vegas. In 1970, he actually initiated a campaign to legalize casinos in Miami Beach. His contrived arrest on a meaningless drug charge was timed, however, for just before Election Day. The passage failed by a large margin even though some polls showed it ahead a few weeks before the election.

The presence of organized crime figures in Florida also contributed to the defeat of a campaign for casinos in 1978. Before Atlantic City opened its casinos, Floridians initiated a ballot proposition for gambling. Although polls showed this proposition with a chance to pass, an active campaign against the casinos led by Governor Reuben Askew caused a major defeat of casinos by a 73 percent to 27 percent margin. In 1986 another vote defeated casinos by a 67 percent to 33 percent margin. In the same election the voters approved a lottery for Florida. Casino forces, this time linked to Las Vegas gambling entrepreneurs, tried again in 1994. They spent over $17 million in their campaign, the most money spent on any ballot proposition in U.S. history up to that date. It was expensive, but again they oversold their product, and the measure went down to defeat with less than 40 percent of the voters favoring casinos. Efforts continued through the rest of the decade to get machine gaming at tracks or other forms of casino gambling into Florida.

The Florida lottery was very successful from its inception. So were the bingo games at the halls of the Native Americans in Florida. It was the Seminoles who generated the initial federal lawsuit over Native gambling. The Seminoles’ first facility was in Hollywood, just north of Miami. They built a second hall in Tampa when the city gave them lands, supposedly for the purpose of having a Native American museum. After the land was put into trust status for the tribe, the Seminoles initiated gambling at the site. A third Seminole gambling hall is in Okechobee. The Miccosukee Tribe developed a gambling hall on the Tamiami Trail west of Miami. The tribes installed various video gambling devices in their halls under the pretense that they were lottery devices. The courts have not agreed. The tribe never won an order forcing the state to negotiate a casino agreement. Nonetheless, the gambling halls each have from 200 to 600 machines, as well as dozens of table games, in addition to their legal bingo games.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

The Federal Wire Act of 1961, passed with the support of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, was aimed at illegal horse race bookies and bettors on sports events. The law prescribed penalties of up to two years prison time and $10,000 fines for persons who “knowingly” use “a wire communication facility for transmission” of bets, wagers, and information assisting betting and wagering on any sports event or contest. Telephone companies could be ordered to cut off service from betting customers when notified of the activity by law enforcement agencies.

Legitimate reporting on sports events by newspaper media was exempt from the act. Similarly it was permissible to transmit messages for betting from one state to another as long as the betting activity was legal in both the states.

The Federal Wire Act was written at a time when telephones with physical wire lines represented the major avenue for interstate communication. Also, horse-race betting was the most prevalent form of illegal gambling. Attorney General Kennedy’s testimony to Congress on the bill mentioned only sports and race betting. Since 1961, telephones have used wireless signals, and there are also other forms of satellite communication signals. The Internet is replacing the telephone for many communicators. Moreover, the Internet carries many kinds of wagering activity in addition to bets on races and sports events. The imprecise fit of the act to current gaming forms has necessitated discussion regarding new legislation to clarify the application of the law. A bill sponsored by Senator Jon Kyle of Arizona won approval in the U. S. Senate but had not come to a floor vote in the House of Representatives as of the end of the 2000 session. That bill would make all gambling on the Internet illegal. Amendments were added to make exceptions for legal race betting and lottery organizations. The bill would give the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission power to enforce the law.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

In the early days of the republic, gambling policy was considered the prerogative of state governments. The new government was structured to be one of delegated powers. The government of the constitution was created by “We the People”, and officials of the government were empowered to make policy only in the areas designated by the “People.” Congress was delegated certain powers in Article I, Section 8, and nowhere on the list were powers to regulate gambling activity. Moreover, the 10th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution specifically reserves the “powers not delegated to the United States… [nor] prohibited” to the states to the “States, respectively, or to the people”. Accordingly, the federal government stayed away from gambling for nearly a century – that is, except for the few lotteries actually run by the government or authorized by the government. Congress was empowered to raise money.

Congress was also given the power to “establish post offices” and to “regulate commerce… among the several States”. Congress turned to these powers when concerns were raised, first about illegal lotteries, and then about the legal but disrespected Louisiana lottery. In 1872, the use of the mails was denied to illegal lotteries. This was followed by a series of laws aimed at curbing the interstate activities of the Louisiana Lottery.

On 19 July 1876, President Grant signed an act that provided legal sanctions against persons using the mails to circulate advertising for lotteries through the mails (44th Congress, Chapter 186). On 2 September 1890, an act was signed, proscribing any advertisements in newspapers for lotteries. (51st Congress, Chapter 980). The Louisiana Lottery managers saw a loophole in these antilottery laws, and they moved their operations to Honduras. They were only a few years ahead of the law, however. On 27 August 1894 (53d Congress, Chapter 349), legislation was passed prohibiting the importation “into the United States from any foreign country… [of] any lottery ticket or any advertisement of any lottery.” All such articles would be seized and forfeited. Penalties of fines up to $5,000 and prison time of up to ten years, or both, would be assessed against violators. The next year (2 March 1895; 53d Congress, Chapter 191), Congress passed an act for the suppression of all lottery traffic through national and interstate commerce. Very specifically, the mails could not be used by lotteries to promote their interests.

These federal laws had a desired effect. They put severe restrictions upon the operators of the Louisiana Lottery. Also, the citizens of Louisiana came to recognize that the operators were bribing state political leaders and extracting exorbitant profits from the lottery, whereas state beneficiaries were being shortchanged. There were also exposures of dishonest games. Under pressure from citizens, the legislature ended the state sponsorship of the lottery in 1905.

In two U.S. Supreme Court decisions, the acts of Congress were determined to be constitutional. That is, they were passed within the scope of the powers of Congress. In 1891, the Court ruled in the case of In re Rapier (143 U.S. 110) that the 1872 prohibition was a valid exercise of congressional power to regulate the use of the mails. In 1903, the justices held in Champion v. Ames (188 U.S. 321) that Congress had the power to pass an appropriate act against a “species of interstate commerce” that “has grown into disrepute and has become offensive to the entire population of the nation”.

Although there were no other legal state-authorized or -operated lotteries until New Hampshire began its sweepstakes in 1964, there were lotteries that sought markets in the United States. There were illegal numbers games in all major cities, and there was the Irish Sweepstakes. The Irish Sweepstakes was created by the Irish Parliament in 1930 as a means of benefiting Irish hospitals. The Irish were well aware that they did not have a substantial marketing potential if they aimed only at customers within the Free State, so they looked outward to Europe and to the United States. At first, they used the mails to promote and sell tickets to customers in the United States; however, the U.S. Post Office successfully intervened with legal action to stop this blatant violation of the 1895 law. Then the Irish Sweepstakes operators turned to smuggling tickets onto U.S. shores. Using ship-to-shore operations, as well as Canadian border cities, they were quite successful into the 1960s and 1970s, when U.S. states began to meet them with competition from their own lotteries.

When radio became established as a viable entertainment media, the federal government found that it was necessary to create the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and to establish uniform regulations for operations of radio stations across the country. The Communications Act of 1934 stipulated rules for advertising “on the air”. Within a few decades, the rules applied also to television signals.

The broadcasting law held that persons would be subject to fines of $1,000 or penalties of one year in prison, or both, if they used radio stations to broadcast or knowingly allow stations to broadcast “any advertisement of, or information concerning, any lottery, gift enterprise, or similar scheme, offering prizes dependent in whole or in part upon lot or chance…” (Federal Communications Act of 1934, Public Law 416, 19 June 1934).

But that was 1934, when no government in the United States had its own lottery. That situation changed in 1963, when New Hampshire authorized a lottery that began operations the next year. By 1975, eleven states had lotteries. The limitations on advertising seemed to be adverse to the fiscal interests of state budget makers. Congress responded to a demand for exemptions to the 1934 act.

In 1975, Congress passed legislation that allowed a state-run lottery to advertise on radio and television stations that only sent signals within the state. Courts later held that the substantial portion of the signals had to be within the state. In 1976, the exemption was expanded to allow advertisements on the air that extended into adjacent states as long as the other states also had state-run lotteries.

In 1988, the exemption included signals into any other state that had a lottery. (Nonprofit and Native American gaming was also exempt from the 1934 act; in 1964 the FCC issued rules allowing horse race interests to advertise “on the air” as long as the advertising did not promote illegal gambling.)

By the last years of the century, the application of the law was in reality an anomaly, with only commercial casino gambling subject to the ban on “lottery” advertising. Lotteries were fully exempt. The anomaly was short-lived, as the 1934 provision was deemed unconstitutional as a violation of freedom of speech after a 1996 U.S. Supreme Court case in a related matter .

No Comments »

No Comments »

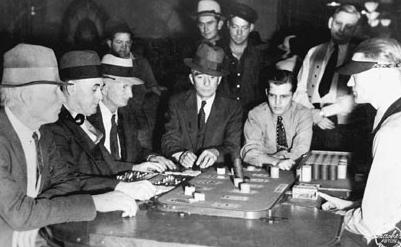

The game of faro was played in France as early as the seventeenth century. The game came to North America through the colonial port of New Orleans. As Louisiana was transferred to the new nation, the game became very popular on Mississippi riverboats and on the Western frontier. The game survived late into the twentieth century in Nevada casinos. Its slow action combined with its low return for the casinos, however, caused houses to drop faro in favor of games such as the increasingly popular blackjack.

A faro game at the Old Las Vegas Club in Las Vegas.

The word faro was derived from the word pharaoh, as the winning card was seen as the “king”. The rather simple luck game is played on a layout called a faro bank. The table has pictures of cards on two sides, the ace through six on one side, the seven at the end in the center, and the eight through the king on the other side. There is also an area marked as “high” on one side. Cards are dealt from a fifty-two-card deck. Suits are not considered, only the card values. After a first card is exposed and discarded, twenty-five two-card pairs are dealt, leaving one remaining card that is not played. The pairs are dealt one card at a time. The first card is a losing card, the second one a winning card. Basically, the players bet that a certain numbered card will appear as the winning or losing card in a pair when the card is next exposed. Correct bets are paid even money. If the card comes up and the other card of the pair is the same, the house wins half of the bet. If a pair does not contain the card, the bet remains until the card comes up in a future pair. For instance, if the bet is that a six will lose, cards are dealt in pairs until a six comes up, either as a winning or losing part of the pair. If two sixes come up, the player loses half the bet. The dealer records which numbers have been played, and so the player can make subsequent bets with a knowledge about chances that a pair will be dealt with that number. The house edge starts at about 2.94 percent when the first pair is dealt and increases against players betting on subsequent pairs if the card bet upon (for example, a six) has not yet appeared. If three of the four sixes have appeared, however, the house edge is gone if the player bets the six will either be a winner or loser when it comes up the fourth time. Players betting on the high can bet that the winning or the losing card will be a higher-valued card.

There is also a variety of combination bets, many of which give the player a very bad disadvantage. The changing odds structures of the game can be calculated as play progresses, giving the game many strategies. The game attracted many systems players, and their many deliberations caused play to be slow compared to other casino games. In early times, systems were probably to no avail as games at the mining camps and on the riverboats were known to often be run by cheaters and sharps.

No Comments »

No Comments »

|

Florida has the third-most-profitable lottery and the third-most-active pari-mutuel enterprise in the United States. The pari-mutuel industry features horse racing, dog racing, and jai alai games. The state has had a long history with underground gambling and with elements of organized crime that ran gambling operations throughout the country and in many other places as well.

Florida has the third-most-profitable lottery and the third-most-active pari-mutuel enterprise in the United States. The pari-mutuel industry features horse racing, dog racing, and jai alai games. The state has had a long history with underground gambling and with elements of organized crime that ran gambling operations throughout the country and in many other places as well.