Archive for the “I” Category

Encyclopedia: Gambling in America - Letter I

Iowa may have the distinction of having more forms of legalized gambling than any other state. The pastoral agricultural land of the Music Man has more than pool halls to corrupt its youth. It has a lottery with instant tickets and massive lotto prizes via Lotto America; it has dog racing and horse racing – thoroughbred, harness, and quarter horse racing. It has bingo games and pull-tab tickets for charities, and it has casinos – on land, on rivers, on lakes, and on Native American lands. Although many of these games were in place by the end of the 1980s, Iowa led the nation in establishing riverboat gaming with legislation that was passed on 20 April 1989.

Even though the Iowa “experiment” led to a massive expansion of gambling throughout the Midwest, in a sense it was supposed to represent a small incremental change in gambling offerings – not a major change in the landscape. The proponents of casinos for Iowa were responding to a general downturn in the agribusiness economy of the state. They were quick to say they did not want Iowa to “be like Las Vegas”. Indeed, during the legislative campaign for casinos, the words casino and gambling were not used. The casino gambling was supposedly just a small adjunct to riverboat cruises designed to recreate Huckleberry Finn excursions down the mighty Mississippi. Only 30 percent of the boat areas could be devoted to casino activities. Ostensibly, the operators would offer many activities on the boats in order to satisfy the recreational needs of the entire family. Originally the boats had to have actual cruises, betting was limited to five dollars a play, and no player could lose more than $200 on a cruise. These limits have been eliminated, and now boats no longer cruise. Instead, they remain docked while players gamble.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

During the last quarter-century of the twentieth century, participation in horserace-betting activities stagnated. Indeed, on-track betting declined considerably, although the decline was offset by a comparable increase in intertrack and offtrack betting. New York’s state authorization of offtrack betting facilities run by a public corporation beginning in 1970 both threatened the viability of on-track wagering and at the same time offered somewhat of a solution to the impending revenue decline. By the mid-1970s there were 100 offtrack betting parlors in New York City alone. New York saw the parlors as a source of public revenue as well as a means to discourage patronage of illegal bookies.

Prior to 1970, only Nevada had offtrack betting activity. Now many other states were examining the New York experience with thoughts of duplicating it. Initially there were no formal provisions requiring that offtrack facilities share revenues with tracks, nor were there mechanisms for requiring that wagers be pooled. Rather, all such arrangements were ad hoc. The tracks across the country perceived major problems, and they turned to Congress for development of uniform policies to answer their concerns. Even though offtrack betting operations agreed that they were adding to the race-betting activity and were sharing some revenues, the tracks felt that their share was not sufficient to offset losses because bettors were coming to tracks in fewer and fewer numbers. A compromise measure was hammered out in Congress, resulting in the passage of the Interstate Horseracing Act of 1978.

The Interstate Horseracing Act recognizes that there are several interests involved in offtrack betting. There are horse owners who essentially realize economic gains through purses when their horses win races. There is the track, basically a private entrepreneurial venture; there is also the host racing state and its racing commission. There is the operation (public in New York but private in other places) that runs the offtrack betting parlor. And there is the state regulatory commission that oversees the offtrack betting activity. Of course, there are always the players – the bettors.

The act stipulated that the tracks and associations of horse owners would meet and agree on how they would split income from fees charged to the offtrack betting operations. The state racing commission would have to ratify the agreement. As with on-track betting revenues, it would be expected that portions of the offtrack betting wagers would go to the state as a tax, to the track owners, and to horse owners through purses. The three parties would then negotiate with the offtrack betting operators for a fee that essentially would be a portion of the money wagered on races (the “take-out”).

The take-out portion going to the track, the owners, and the host state would be less than the amount taken from the track bettors, as it also had to be shared with the offtrack betting facility and the offtrack betting state. The Interstate Horseracing Act requires that the overall take-out percentage from the offtrack betting activity be the same take-out rates as charged to on-track bettors. This protects the tracks from price competition.

The act also stipulated that the offtrack betting facility cannot conduct operations without the permission of any track within sixty miles of the facility, or if there are no such tracks, then the nearest track in an adjacent state. The act did not address the subject of simulcasting race pictures between the tracks and the offtrack betting facilities.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

Gambling through the Internet became an established activity in the mid-1990s, causing great concern to many interests – governments as well as private parties seeing danger in easily accessible gambling. Gambling through the Internet became an established activity in the mid-1990s, causing great concern to many interests – governments as well as private parties seeing danger in easily accessible gambling.

The Internet system was developed three decades ago by the U.S. Department of Defense in order to connect computer networks of major universities and research centers with government agencies. The growth of the system into what has now become potentially the most active and most encompassing form of communication had to await the advent of the personal computer and its widespread acceptance. By the end of 1998 there were over 76 million Internet stations providing access to 147 million persons in the United States – mostly in their homes. An equal number of computers with Internet access are found in other countries.

There are an estimated 800 host computer sites that either provide gambling directly or provide information services for gamblers. Approximately sixty Internet sites, located mostly in foreign lands, accept bets on a variety of events. Most wagering is on sports events, but several sites also conduct lottery or casino game-type betting. In order to make a wager, a player with Internet access must first establish a financial account with a gambling Internet enterprise. Although the enterprise is typically located in another country, the bettor can send money to the enterprise by using a credit card, debit card, a bank transfer of funds, or personal checks. Wagers can then be made, and the account is adjusted according to wins and losses.

Internet gambling activity has not yet become a major part of the worldwide gaming industry, but it appears to be growing, and it possesses possibilities for becoming much larger than at present. The National Gambling Impact Study Commission reported that in 1998 there were nearly 15 million people wagering on the Internet from the United States, providing the Internet gaming entrepreneurs with annual revenues of from $300 million to $651 million (National Gambling Impact Study Commission 1999, 2–15, 2–16). This would represent an amount equaling about 1 percent of the legal betting in the land. Gaming analyst Sebastian Sinclair estimated that revenues could reach $7 billion in the early twenty-first century (National Gambling Impact Study Commission 1999, 2–16). If the expansion comes, it will essentially be because the Internet offers bettors a very high level of convenience for their activity, and it also offers a privacy they may especially want because of the illegal (or at best quasi-legal) nature of the activity. It is easier to sit at home and wager on a computer than it is to drive to a casino sports book—especially when we consider that the only legal sports books are in Nevada. The computer is also quicker than bookie telephone betting services. It is also less likely to be intercepted by law enforcement officials.

There are downsides to Internet betting that may provide dampers to the wagering activity. The first issue is integrity. Although a player betting on a sports event has an assurance that he has legitimately won or lost a bet (assuming there are independent news reports on the sports event bet upon), other players wagering on lotteries or, especially, casino-type games have no firm guarantees that the results of the wagering are totally honest. To be sure, some Internet sites are licensed by governments, giving an appearance of legitimacy. The very staid government of Liechtenstein authorizes operation of an Internet lottery, and several Caribbean entities, such as Antigua, St. Kitts, and Dominica, oversee many Internet sites offering a variety of games, as well as sports betting. The oversight activities, however, consist almost entirely of collecting fees from the operators.

The Federal Wire Act of 1961 was confined to betting on races and sports events. It did not speak to casino-type games and lotteries. Hence, some betting on some computer-type games may possibly be legal, at least in the eyes of the federal government – that is, at the present time.

To address these questions with clarity, and to fill the possible gap in the 1961 law, U.S. senator Jon Kyl of Arizona has promoted legislation to amend the Federal Wire Act. His proposed amendment won approval in the U.S. Senate, but as of the end of the 2000 session, it had not come to a floor vote in the U.S. House of Representatives. The Kyl bill would make any and all gambling on the Internet illegal, and it would give the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission powers to enforce the law. As the bill was moving toward passage, it was amended to allow exceptions for legal race betting and lottery organizations.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

Insurance has sometimes been compared with gambling. After all, an insurance company acts like a casino as it asks its clientele to wager on whether they will live or die, whether they will be healthy or sick, whether their house will burn down or not, whether they will be victimized by thieves, or other sad circumstances. It would seem that characteristics of insurance could meet the elements in the definition of gambling: Customers put up money (consideration), and they win a settlement (prize) depending upon a factor of chance (whether or not they become a victim). And of course, like a casino, the insurance company charges a fee for the service of offering its product, and the insurance company also sets the prize structure so that it will make a profit – the odds are in the favor of the insurance company. Insurance has sometimes been compared with gambling. After all, an insurance company acts like a casino as it asks its clientele to wager on whether they will live or die, whether they will be healthy or sick, whether their house will burn down or not, whether they will be victimized by thieves, or other sad circumstances. It would seem that characteristics of insurance could meet the elements in the definition of gambling: Customers put up money (consideration), and they win a settlement (prize) depending upon a factor of chance (whether or not they become a victim). And of course, like a casino, the insurance company charges a fee for the service of offering its product, and the insurance company also sets the prize structure so that it will make a profit – the odds are in the favor of the insurance company.

These things being said, or to a degree admitted to be true, there are still major distinctions between gambling and insurance, distinctions that allow me to neglect the concept of insurance in the remainder of this encyclopedia. Paul Samuelson’s seminal volume on economics points out the differences. In his section on economic impacts of gambling, Samuelson writes that gambling serves to introduce inequalities between persons and instabilities of wealth. Insurance has the directly opposite consequences. Insurance gives people the opportunity to achieve stability in the face of risks that are often inherent in the nature of things – risks of disease, of fire, of lost property. For a small sum of money, people can purchase policies that will guarantee that the costs of a disaster will not ruin their lives or their families. Gambling purposely introduces risk into a society that is stable; insurance purposely exists to avoid risks. Actually, the insurance company spreads the risks of disasters to a single person among a very large number of persons who buy insurance policies.

Insurance companies may sell policies that cover only a certain set of circumstances. The person purchasing insurance is limited to buying coverage only for “insurable interests”. The insurable interest cannot be as frivolous as the turning of a card or where a ball falls on a spinning wheel. The interest must be a real concern to the policyholder. One can insure his or her own life but cannot insure the life of a total stranger. Insurance companies must limit the amount of insurance sold to values relative to the risks the insurance seeks to avoid. A house can be insured against fire, but only up to the full value of the house. Similarly, health can be insured up to the cost of treatment and collateral losses such as wage losses. The limits on insurance coverage preclude the gambler’s behavior of chasing losses. If the “bad” event does not occur, and a premium payment is thus lost, the insured person cannot simply double the bet for the next period of time. The insurance company and the insured both have disincentives for purchasing excessive policies. Insurance companies make those wishing to have large life insurance policies subject themselves to many medical examinations, including full health screenings. Newly covered persons with health insurance may not be able to receive benefits for a number of months.

By gambling, a person is seeking risks that might severely upset his or her financial stability. By buying insurance, a person is avoiding risks. On the other hand, if a person with a house, other property, or a family dependent upon him or her does not insure the house or property against destruction or himself or herself against illness or death, that person is gambling with fates that strike people often randomly, albeit with some rarity (in short periods of time), but almost certainly over large periods of time.

Gambling activity can be and often is very destructive to personal savings. Insurance, on the other hand, can be seen as an alternative means of savings—savings for a rainy day in some cases. In the case of whole life insurance, savings and investment are encompassed into the policies. Although in some respects the notions of insuring against the occurrence of certain natural events and betting on the occurrence of contrived events may appear quite similar, in actuality they are not very much alike.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

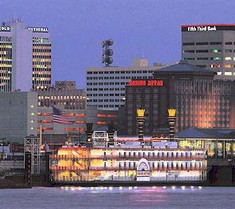

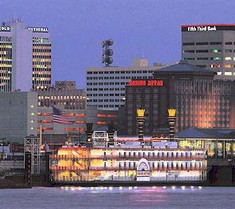

Legalized gambling came late to Indiana. Before the state began its lottery in 1991, it had been one of only three in the United States that had no legal gambling. Although the effort to establish the lottery was ongoing, a campaign for casinos was also taking place. Following several years of lobbying efforts and studies of a variety of proposals, the state legislature passed a riverboat gaming law over the veto of Gov. Evan Bayh in 1993. The next legislative session authorized horse-race betting within the state. Legalized gambling came late to Indiana. Before the state began its lottery in 1991, it had been one of only three in the United States that had no legal gambling. Although the effort to establish the lottery was ongoing, a campaign for casinos was also taking place. Following several years of lobbying efforts and studies of a variety of proposals, the state legislature passed a riverboat gaming law over the veto of Gov. Evan Bayh in 1993. The next legislative session authorized horse-race betting within the state.

The strongest motivation for approving casino gambling was provided by the fact that several casino boats in Illinois were drawing much of their revenue from Indiana residents. Four Illinois casinos were in suburban Chicago within fifty miles of the Indiana border, and another license was held by a boat in southern Illinois within a short driving time of the Evansville metropolitan area.

Indiana’s new law authorized licensing of eleven casino boats for counties bordering Lake Michigan waters as well as on the Ohio River and Patoka Lake. The licenses can be granted only if the residents of the county where the boat operates approve casino gaming in a referendum vote. Most of the gaming-eligible counties held votes; some were positive and some were negative. The Patoka Lake license has not been activated, as the United States Army Corps of Engineers was determined to own the rights to control the water of the lake.

On 9 December 1994 the first two licenses were awarded, but there were legal difficulties. The federal Johnson Act prohibited gaming on the Great Lakes (see The Gambling Devices Acts [the Johnson Act and Amendments]). The state had claimed an exemption to the provisions of the act in the riverboat legislation, but the matter had to be clarified in Congress, with the attachment of a rider to the Coast Guard Reauthorization Act of 1996 that exempted Lake Michigan waters from the Johnson Act for purposes of gaming on Indiana-licensed casino boats. Difficulties with the Ohio River arose, as the waters of the river were within Kentucky. This was resolved by requiring boats on the river to cruise within a short distance of the shore.

The 1993 legislation created an Indiana Gaming Commission of seven members appointed by the governor. The governor also appointed the executive director of the commission. Nine casino boats were in operation by 1999. They accomplished at least some of their original purpose. Revenues for Illinois boats experienced a small decline while Indian boats surpassed Illinois revenues.

The commission has a very wide range of powers. It may make any rules necessary for carrying out to mandates of the 1993 act. Additionally, it accepts applications for licenses and conducts all investigations of applicants, including investigations into personal character. It selects the licensees and oversees their operations. It takes all disciplinary actions if rules are violated and may revoke licenses, which are granted for a five-year period. The boats must be at least 150 feet in length and have the capacity to carry 500 persons.

The first boat to begin operations was Casino Aztar in Evansville; it opened its doors for gaming on 8 December 1995. Casino Aztar is a 2,700-passenger boat with 35,000 square feet of gaming space.

Two boats started gaming on 11 June 1996. Both are docked in Gary, Indiana. Donald Barden’s Majestic Star is a 1,500-passenger vessel with 25,000 square feet of gaming space. Donald Trump’s Trump Casino occupies 37,000 square feet of gaming space on a 2,300-passenger boat.

On 29 June 1996, the Empress Casino boat began cruises in Hammond. The 2,500-passenger vessel has a gaming floor of 35,000 square feet. Hyatt’s Grand Victoria Casino and Resort started cruises in Rising Sun on 4 October 1996. The boat was the first casino to invade the Cincinnati, Ohio, metropolitan area. It carries 2,700 passengers and has a gaming floor with 45,000 square feet.

The Argosy Casino began operations on the Ohio River at Lawrenceburg, also near Cincinnati, Ohio, on 13 December 1996. The 4,000-passenger yacht has a gaming floor of 74,300 square feet.

The Showboat Mardi Gras Casino started cruises out of East Chicago on 18 April 1997. It has gaming space of 53,000 square feet and carries 3,750 passengers. On 22 August 1997, the fifth Lake Michigan boat license was activated as the Blue Chip Casino opened in Michigan City. The 2,000-passenger vessel has 25,000 square feet of gaming space. The ninth boat to begin operations is at Bridgeport, across from the Louisville, Kentucky, metropolitan area. It is operated by the same company that runs the Caesars Palace casino in Las Vegas. The City of Rome riverboat carries 3,750 passengers and has 93,000 square feet of gaming space. Gaming began in late 1998.

The tenth license is reserved for the Ohio River area and may be granted for a boat near either the Cincinnati or the Louisville population base.

The casino boats must go out into waters for cruises, although one off Lake Michigan has a special channel for its cruises. An amendment to the original 1993 law clarified conditions when the boats could remain docked. Basically, these include any times the boat captain would determine that safety required that the boats remain docked. In any case, the boats are required to have two-hour cruises. If the boat is docked, the cruises are mock cruises.

The casino boats pay a gross gaming tax of 20 percent of their win. Of this amount, one-quarter goes to the city where the boat is docked (or county if not in a city), and three-quarters goes to the state’s general fund. There is a three-dollar admission fee, which is also shared among state and local governments.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

By the time the riverboat casinos of Iowa were in operation in 1991, the state of Illinois reacted to the notion that their citizens would be asked to cross the Mississippi River to gamble in another state. Illinois lawmakers feared that Iowa boats would simply become parasites upon the Illinois economy, taking both profits and tax moneys away from Illinois. Illinois knew gambling. Racetracks had been in operation since the days of the Depression. A lottery began selling tickets in 1972. Bingo games were very popular, especially in urban areas. Also, the state had considerable experience with illegal casino-type organizations. These forms of gambling would not be adequate to meet the marketing threat from Iowa. By the time the riverboat casinos of Iowa were in operation in 1991, the state of Illinois reacted to the notion that their citizens would be asked to cross the Mississippi River to gamble in another state. Illinois lawmakers feared that Iowa boats would simply become parasites upon the Illinois economy, taking both profits and tax moneys away from Illinois. Illinois knew gambling. Racetracks had been in operation since the days of the Depression. A lottery began selling tickets in 1972. Bingo games were very popular, especially in urban areas. Also, the state had considerable experience with illegal casino-type organizations. These forms of gambling would not be adequate to meet the marketing threat from Iowa.

The Illinois legislature legalized riverboat casinos. They acted quickly, with legislation on the governor’s desk in January 1990 and the licensing process starting in February 1990. Ten licenses were authorized for the state, with each license holder being able to have two boats. Each boat would have a maximum capacity of 1,200 passengers. The boats would have to be on navigable waters; however, no boat could be inside of Cook County. This restriction was offered as a concession to the horse-racing tracks near Chicago, which is in Cook County. The tracks feared that the boats would have an unfair competitive edge over racing. In 1998 the restriction was removed, and a boat was authorized for the community of Rosemont.

The casino operations began in April 1991, just after Iowa boats began operations. The Illinois lawmakers decided to meet the threat of Iowa competition by offering more “liberal” gaming rules. There was no $5 bet limit, nor was there a $200 loss limit per cruise. The boats were required to make cruises, unless there was bad weather. In such a case there would be “mock cruises”, with players entering and leaving the dockside boat at set times. The Illinois boats did very well compared to the Iowa boats in their first years of operation. Therefore, Iowa felt the necessity of eliminating its $5 betting and $200 loss limits in 1994.

Well before the advent of riverboat casinos, there were efforts to bring legal casino gambling to Illinois. During the Prohibition and World War II eras, there were several illegal gambling halls in the state; however, their numbers and the openness of their operations declined in the 1950s and 1960s. Instead, an effort grew to legalize casinos.

In the late 1970s Mayor Jane Byrne suggested having casinos to produce extra revenues for snow removal activities in Chicago. The Navy Pier site was selected for casino gambling. The efforts were stymied by Springfield lawmakers. In 1992 Chicago mayor Richard Daley conferred with several Las Vegas operators, and together they proposed a $2 billion megaresort complex for the city. The project engendered considerable support; however, it was defeated owing to the opposition of Gov. James Edgar.

The Illinois riverboat casinos are regulated by a five-member Illinois Gaming Board appointed by the governor. The board issues licenses, collects taxes, and enforces gaming rules with inspections, hearings, and fines as necessary. The board may also revoke licenses. The boats pay license application fees of $50,000 each. After operations begin, they pay an admission tax of $2 per passenger and also pay 20 percent of their gaming win (players’ losses) as a state tax. Half of the admissions tax and one-fourth of the gambling tax are returned by the state to the local city or the county where the boat is docked. Each boat has a single docking site. The ten boats have generated over $1.2 billion a year.

No Comments »

No Comments »

Idaho was the next-to-last state (before South Carolina in 2000) having an existing form of legal gambling made illegal on a statewide basis. Through the 1930s and 1940s slot machines were permitted under state law on a local option basis. In 1948, however, the voters decided that all the machines should cease operations. Idaho was the next-to-last state (before South Carolina in 2000) having an existing form of legal gambling made illegal on a statewide basis. Through the 1930s and 1940s slot machines were permitted under state law on a local option basis. In 1948, however, the voters decided that all the machines should cease operations.

Since then, pari-mutuel gambling for thoroughbred, quarter horse, and dog races has been authorized, as has charitable gambling. A lottery began operations in 1991. Several tribes in the state offered high-stakes bingo games; however, they began serious negotiations for casino gambling in the early 1990s. The state refused to negotiate, using the 11th Amendment as a defense (the 11th Amendment bans suits against states in federal courts except in certain circumstances). The Coeur d’Alene tribe of northern Idaho decided to try something new. They instituted a nationwide lottery using telephone lines and the Internet. Considerable litigation ensued; however, the game was not sufficiently profitable, and the tribe dropped it. The tribe has installed nearly 500 machines at their gaming facility, claiming that the machines are lottery games. The state has objected to their presence, but there has been no concerted action to remove them.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

|

Insurance has sometimes been compared with gambling. After all, an insurance company acts like a casino as it asks its clientele to wager on whether they will live or die, whether they will be healthy or sick, whether their house will burn down or not, whether they will be victimized by thieves, or other sad circumstances. It would seem that characteristics of insurance could meet the elements in the definition of gambling: Customers put up money (consideration), and they win a settlement (prize) depending upon a factor of chance (whether or not they become a victim). And of course, like a casino, the insurance company charges a fee for the service of offering its product, and the insurance company also sets the prize structure so that it will make a profit – the odds are in the favor of the insurance company.

Insurance has sometimes been compared with gambling. After all, an insurance company acts like a casino as it asks its clientele to wager on whether they will live or die, whether they will be healthy or sick, whether their house will burn down or not, whether they will be victimized by thieves, or other sad circumstances. It would seem that characteristics of insurance could meet the elements in the definition of gambling: Customers put up money (consideration), and they win a settlement (prize) depending upon a factor of chance (whether or not they become a victim). And of course, like a casino, the insurance company charges a fee for the service of offering its product, and the insurance company also sets the prize structure so that it will make a profit – the odds are in the favor of the insurance company. Legalized gambling came late to Indiana. Before the state began its lottery in 1991, it had been one of only three in the United States that had no legal gambling. Although the effort to establish the lottery was ongoing, a campaign for casinos was also taking place. Following several years of lobbying efforts and studies of a variety of proposals, the state legislature passed a riverboat gaming law over the veto of Gov. Evan Bayh in 1993. The next legislative session authorized horse-race betting within the state.

Legalized gambling came late to Indiana. Before the state began its lottery in 1991, it had been one of only three in the United States that had no legal gambling. Although the effort to establish the lottery was ongoing, a campaign for casinos was also taking place. Following several years of lobbying efforts and studies of a variety of proposals, the state legislature passed a riverboat gaming law over the veto of Gov. Evan Bayh in 1993. The next legislative session authorized horse-race betting within the state.

Idaho was the next-to-last state (before South Carolina in 2000) having an existing form of legal gambling made illegal on a statewide basis. Through the 1930s and 1940s slot machines were permitted under state law on a local option basis. In 1948, however, the voters decided that all the machines should cease operations.

Idaho was the next-to-last state (before South Carolina in 2000) having an existing form of legal gambling made illegal on a statewide basis. Through the 1930s and 1940s slot machines were permitted under state law on a local option basis. In 1948, however, the voters decided that all the machines should cease operations.