Archive for the “J” Category

Encyclopedia: Gambling in America - Letter J

“Canada Bill” Jones (1820–1877) was the master of three card monte in the middle years of the nineteenth century. Stories are told about characters in the gambling world, and some of the best are told about Canada Bill. When he was circulating through the South during the post–Civil War years conning people with his monte games and looking for any action, he found a poker game. As he entered the game he was warned that it was a crooked game. He responded simply, “I know, but it is the only game in town”. Certainly the same story has been told about other gamblers. It was quite likely to be true about Canada Bill, however, who in his lifetime won millions of dollars on his own specialty game. He then turned around and lost the money gambling in other games, usually poker and faro games.

After his funeral in Reading, Pennsylvania, in 1877, it was reported that while two gamblers were lowering the coffin into the ground, one said, “I’ll bet you my hundred against your fifty”. “On what?” said the other. “I’ll bet that he isn’t in the coffin”. He then related that Canada Bill had squeezed out of tighter boxes in his lifetime. Indeed, he had gotten out of town ahead of his victims on more than several occasions. During the 1850s he traveled the Mississippi River with his monte operation in a partnership with George Devol. Devol was a fighter. But Canada Bill was only 130 pounds and afraid of a fight. He knew how to get Devol to make a defensive stand as he led the escape from the “tight” situations.

Bill Jones was born in Yorkshire, England, to a family of gypsies. He was raised among fortune-tellers and horse traders and thieves. He learned that the secret of living involved using con jobs. In his early twenties he moved to Canada, whence came his nickname. There he met his gambling mentor, Dick Cady, who taught him the sleight-of-hand operations of three-card monte, a card game that worked like the proverbial shell game. When Jones heard about the riverboats, he left the frozen tundra behind, becoming a man of the South.

After touring the river for several years, he worked his scams on the new railroads in the United States. He actually proposed to one line that he be given a monopoly concession for the train. He was denied the exclusive opportunity and had to travel with other gamblers – probably guaranteeing that he would not keep his winnings. Canada Bill was the best at three card monte, as he could almost change a card as he was throwing it down to the table. In his later years he worked county fairs and a world fair, and also racetracks. He was unlike other professional gamblers of the era, as he did not dress to impress. Quite the opposite, he always appeared as the rube, unshaven, in rumpled oversized clothes, looking like a sucker ready to be taken. He often said that “suckers had no business with money, anyway”. He was what he appeared to be. He died a pauper.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

Pachinko may be a funny sounding word. Actually it is derived from the sound – “pachin-pachin” – that is made by balls as they bounce down the face of the game board toward winning or losing positions. It may be a funny-sounding game, but it produces some serious wins. Pachinko may be a funny sounding word. Actually it is derived from the sound – “pachin-pachin” – that is made by balls as they bounce down the face of the game board toward winning or losing positions. It may be a funny-sounding game, but it produces some serious wins.

Pachinko has its origins outside of Japan. Some suggest that the game comes from Europe, but most find beginnings in the United States. The Corinthian game was played in Detroit in the early 1920s. The game was played with a board placed on an incline. Balls were shot up one side of the board and then fell downward onto circles of nails (arranged like Corinthian architecture) and bounced into winning slots or fell into a losing pool at the bottom. Players were given scores and awarded prizes for their play.

The game developed in two different directions. In the United States it graduated into the popular pinball games that were found in recreation halls across the land until computerized games replaced them in the 1960s. The Corinthian game moved to Japan, and in the 1930s parlors were developed offering play. The game board was placed upright into a vertical position to save space. Machines were also converted so that the balls could come out of the machine in increased volumes if winning placements were made.

Soon the machine was the most popular recreational game in Japan. In 1937, however, Japan commenced military action in China, and the nation assumed a wartime posture. The game was made illegal as plants making the games were converted into munition factories. The government did not want individuals to waste time at play, and many of the players were drafted for military service.

After the war the machines were made legal once again. The government now encouraged play, as the occupying armies used play as a means to distribute scarce goods to the public – cigarettes, soap, chocolate. Players “won” balls from the machine, then exchanged the balls for merchandise. No cash prizes were allowed (which is still the case). In ensuing decades the machines were refined. Shooting mechanisms enabled players to put over 100 balls a minute into play. Pachinko machines incorporated new games within the game. Slot machine–type reels were placed in the middle of the playing board. As balls went into winning areas, the reels spun, enabling greater prizes to be won if symbols could be lined up in winning combinations.

Machine operators have the opportunity to make payouts greater or smaller by moving the nails on the surface of the playing boards. Players find that when the nails are farther apart, the balls are more likely to fall into a winning position. Experienced players will look for such machines. Also, they will play on certain days when the weather may cause the nails to be loosened. Particular players may be consistent winners; however, even a very inexperienced player can achieve wins when a ball activates the slot-type reels and they end up in a jackpot position. Typically the machines pay out a maximum of balls worth about $160 for a top jackpot.

A new variation of the game called pachi-slo has been introduced. The game is essentially like the reel slot machines found in casinos all over the world. After the reels are activated, however, they may be stopped individually by the player’s pushing buttons. With a special skill the player is supposed to be able to line up symbols in winning patterns. The reels spin so fast, however, that almost all winners claim their prizes through luck. Although pachinko wins are conveyed in balls from the machine, pachi-slo machined use tokens for play, and tokens come out for winners.

With both types of machines the balls and tokens are converted by a weighing machine into tickets with winning amounts written upon them. The tickets are traded for prizes at a special booth within the parlor. Prizes popularly won include cigarettes, music tapes, and compact discs.

Well over 90 percent of the winning players, however, choose to trade tickets for small plastic plaques, which ostensibly have value in and of themselves. Usually they include small pieces of gold or silver. But no player wants the little bit of precious metal. Instead, they take the plaques to a designated money exchange booth that is usually very near the pachinko parlor. There they receive cash payments. The process of converting balls or tokens into tickets into prizes into cash costs the player about 25 percent of the prize. That is, 100 balls for play will typically cost 400 yen (about $5). If a player wins back the 100 balls, the ticket will enable him to trade the win for a prize worth 400 yen retail. The plastic plaque may be traded at the money exchange for 300 yen cash. The parlor does not really care which way the player goes. After all, the retail merchandise costs the parlor only 300 yen. The exchange booth operators may take a portion of the win when they sell the plaque, as they are a separate business. Even so, the parlor owners sometimes may have close ties to the exchange businesses.

Today there are approximately 18,000 parlors in Japan. Collectively they have 4 million machines. About 80 percent of the machines are pachinkos and the rest pachi-slos. The parlors may also have rooms with other kinds of amusement machines that give prizes. Each machine wins an average of over $5,000 per year, substantially less than the slot machines of U.S. casinos. The machines cost only about $1,000 each, however, and halls choose to have an excess of machines so that experienced players as well as others can have the opportunity to select machines for play. The United States has about one slot machine for each 400 residents, but Japan has one gaming machine for each thirty residents. And that makes for a lot of gambling.

The reluctance of Japan to embrace casino-type gambling in part derives from a feeling that gambling enterprise is closely connected to bad influences – in Japan, that might mean the Yakusa, or organized crime. There is a fear that the Yakusa has ties to the pachinko industry.

Like the democracy of Pericles and the Golden Age of Athens, citizenship privileges in Japan are for the most part reserved for people of Japanese origin. Residents with Korean or Chinese family ties may be excluded from entrance to the major corporations of the land, and for some of the time after World War II, their children were not allowed into the universities. Those with entrepreneurial spirit had to “go it alone”. These “foreign” (so considered even if native born) Japanese developed mom-and-pop retail businesses, and they also gravitated toward pachinko. At first most parlors were small and independently owned. Also, pachinko, although very popular, was considered somewhat unclean – perhaps like pool, pinball, and slot machines were in years past in the United States. The traditional Japanese did not want to associate with the business. Organized crime groups also moved into the industry, many with Korean ties. Today the police worry that some pachinko parlor funds are utilized to support drug activities and gun smuggling. There is an ongoing fear that funds are skimmed and sent to North Korea where the Communist regime uses them to purchase nuclear materials.

These suspicions have led various members of the industry to band together to form an association with the goal of cleaning up the industry as well as the image of the industry. The group is hoping that the government will revise the prize structure of the games so that players can win cash prizes directly from the machines. The police are reluctant to do so, because, as one National Police director told me during an interview in Tokyo on 10 August 1995, “we don’t want gambling in Japan”.

<

2 Comments »

2 Comments »

The Japanese are known in Las Vegas as “prized customers”, “top-rated quality players” and “high rollers”. Deservedly they are given first-class treatment whenever they hit the Strip. Moreover, it is well recognized that Japanese manufacturers supply some of the best gaming equipment for U.S. casinos. Japanese have even owned gambling halls in the United States. Although it is known that the Japanese people are very attached to gambling enterprise, there may be a false notion that the Japanese do not gamble very much at home. Nothing could be further from the truth. Per capita gaming in Japan far exceeds that present in the United States. The Japanese are known in Las Vegas as “prized customers”, “top-rated quality players” and “high rollers”. Deservedly they are given first-class treatment whenever they hit the Strip. Moreover, it is well recognized that Japanese manufacturers supply some of the best gaming equipment for U.S. casinos. Japanese have even owned gambling halls in the United States. Although it is known that the Japanese people are very attached to gambling enterprise, there may be a false notion that the Japanese do not gamble very much at home. Nothing could be further from the truth. Per capita gaming in Japan far exceeds that present in the United States.

Over the years, trade journals have given only the slightest attention to the games of Japan. International gaming charts indicate that the country has lotteries and pari-mutuel racing, but no casinos. Comments on what various countries are doing regarding gaming almost always leave Japan out. In the history of the now defunct Gambling Times, there was only a short article on motor boat racing in Japan and another one on amusement machines. The leading trade journal, International Gaming and Wagering, devoted only one short survey article to Japan gaming in 1994. It would be helpful if the literature gave more attention to this gambling-intense country, perhaps in an elaboration of the 1994 piece.

Gambling, as we would call it, or entertainment with prizes, as the Japanese police would call it, is very big in Japan. Japan has 130 million people—approximately half the population of the United States. Yet the total gambling revenue of Japan is more than equal the $35 billion gross win of U.S. casinos, lotteries, and pari-mutuel racing venues.

Part of the illusion that Japan does not gamble comes from the fact that there are no casinos in Japan – that is, casinos in the U.S. sense of the word. But make no mistake about it, there are gambling halls in Japan – almost 20,000 of them. They offer players opportunities to win prizes by playing “skill” games on pachinko and pachi-slo machines. Even though there are elements of skill in pachinko, luck is a major factor in the game. Thirty million people play on the 4 million machines around the country. The machines produce wins equivalent to US$21 billion each year. In other words, the entertainment machines with prizes win more money than is won by all the casinos – commercial, Indian, and charity – of the United States.

Pari-mutuel wagering is permitted both on and off track for motorboat, bicycle, and horse racing. Japan is unique in being the only place where wagering is offered for bike and boat races. Large stadium structures permanently line banks of rivers where the boat races take place. As there is “skill” in making wagers, the government denies that there is gambling involved in the enterprise. The race betting may not be “gambling”, but make no mistake about it, it is big-time wagering. The Japan Derby (Imperial Cup) horse race each fall (November) produces a handle exceeding the collective handle of the Triple Crown in the United States.

Lotteries are in a growth phase. Until recent years, the games were passive weekly draws that were slow and did not permit the player much involvement in selection of numbers. Instant games have been played since the late 1980s, however, and in 1995 a numbers game in which the player selects the number was added. A national lottery run through the Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank leads the world in sales for a single lottery.

<

No Comments »

No Comments »

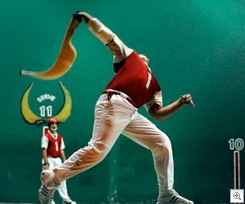

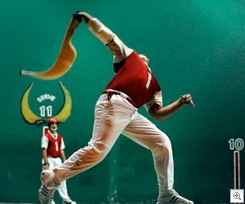

Jai Alai is a game that is played on the basic principles used for handball and racquetball games. Jai alai contests are used for pari-mutuel betting in Florida, Connecticut, and Rhode Island and for almost a decade in the MGM casinos of Las Vegas and Reno, Nevada. Jai Alai is a game that is played on the basic principles used for handball and racquetball games. Jai alai contests are used for pari-mutuel betting in Florida, Connecticut, and Rhode Island and for almost a decade in the MGM casinos of Las Vegas and Reno, Nevada.

The game is considered the oldest ball game played today; it is also considered the fastest game played. Players either compete as individuals or in teams of two. The game is played on a very large court, 177 feet long, 55 feet wide, and 55 feet high. The playing facility is called a fronton. The ball is very hard – harder than a golf ball – and is about three-fourths the size of a baseball. The ball, called a pelota, is propelled by the players toward the front wall of the court. The players hold a cesta, which is a curved basket that extends from one of their arms. They catch the ball in the basket device and then without letting it settle, they propel it back to the front wall. They must retrieve and return the ball before it hits the floor two times. The balls may move as fast as 150 miles per hour in the games, faster than any other ball in any game.

The game of jai alai may have had ancient predecessors, as the notions behind handball have been found in many prehistoric societies. In its present form, however, the game is traced to Basque villages in the Pyrenees of France and Spain. The origins of the game may go back to the fifteenth century. Mythmakers suggest that the game may have been the invention of St. Ignatius of Loyola, who – like his compatriot St. Francis Xavier – was Basque. What is less mythical is the fact that the game was played during religious festival occasions in the Catholic region. The words jai alai mean “merry festival”. The game has also been known as pelota vasca or Basque vall. The game is celebrated in the classic art of Spain. Francisco Goya created a tapestry called Game of Pelota for the Prado in Madrid. Many mythical heroic characters of Basque tradition were pelota players.

As the Basques and persons from the surrounding regions migrated to the Western Hemisphere, they brought the game with them. It came to Cuba by the beginning of the twentieth century, and it was displayed at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904. (Castro closed down games in 1960 as he closed the Cuban casinos). It came to Florida in 1924. Although the game enjoyed some natural popularity for its basic excitement, it did not draw large crowds until 1937, when the Florida legislature authorized pari-mutuel betting on the winners of the games.

In the jai alai game there are eight players (or eight teams of two players each). They play round robin matches. A player (team) who wins a point remains in the game; the loser is replaced with another player (team). They keep playing until one player (team) has scored seven points. In a sweep, one player could score seven straight points but would have to do so by scoring against every other team in the contest. The contests result in one winner with seven points and second- and third-place players (teams) with the next highest number of points. If there is a tie, the tying teams play off for their position. Those making wagers can bet the basic win, place, and show as in horse racing. Jai alai contests also were innovative because they created the quinella, perfecta, and exacta bets. A trifecta bet is also used.

Florida developed many frontons, but play levels pale in comparison with other betting venues such as bingo halls, horse tracks, and Native American casinos. The MGM Grand Hotels of Las Vegas and Reno had frontons until the mid-1980s. Connecticut authorized jai alai betting in the early 1970s, as did Rhode Island in 1976. Efforts to get the sport accepted elsewhere in North America for pari-mutuel wagering have not been successful.

<

1 Comment »

1 Comment »

|