From its earliest days, Las Vegas catered to travelers. Its springs watered not only the crops of local Indians but also the meadows (las vegas is Spanish for “the meadows”) that in the 1830s supported an oasis for whites traveling the Old Spanish Trail between New Mexico and southern California. In 1855, Mormons built a fort and mission there, which also acted as a hostel for those plying the route between Utah and the church’s colony in San Bernardino, California. Following the Civil War, several farm-ranches occupied the valley until 1905, when Sen. William Clark, principal owner of the newly created San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, purchased Helen Stewart’s ranch for $55,000. On this tract he platted his Las Vegas Townsite, a division town complete with yards, roundhouse, and repair shops. In addition, he used the ranch’s water rights to supply his town and the thirsty boilers of his steam locomotives.

From its earliest days, Las Vegas catered to travelers. Its springs watered not only the crops of local Indians but also the meadows (las vegas is Spanish for “the meadows”) that in the 1830s supported an oasis for whites traveling the Old Spanish Trail between New Mexico and southern California. In 1855, Mormons built a fort and mission there, which also acted as a hostel for those plying the route between Utah and the church’s colony in San Bernardino, California. Following the Civil War, several farm-ranches occupied the valley until 1905, when Sen. William Clark, principal owner of the newly created San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad, purchased Helen Stewart’s ranch for $55,000. On this tract he platted his Las Vegas Townsite, a division town complete with yards, roundhouse, and repair shops. In addition, he used the ranch’s water rights to supply his town and the thirsty boilers of his steam locomotives.

The little whistlestop struggled along into the 1930s, experimenting with commercial agriculture and other small industries to supplement its transportation economy, but without success. The first seeds of change came in 1928 when Congress appropriated funds for building Hoover Dam. Construction began in 1931, the same year that the state legislature re-legalized gambling and liberalized the waiting period for divorce to six weeks. The dam was an immediate tourist attraction, drawing 300,000 tourists a year. But even with these visitors and the 5,000-plus men who toiled on the project, gambling remained a minor part of Las Vegas’s economy. When construction ended in 1936 and the dam workers left, the city experienced a mild recession. By decade’s end, the town’s population numbered only 8,400.

The real trigger for casino gambling was World War II. The sprawling Desert Warfare Center south of Nevada’s boundary with Arizona and California, along with Twentynine Palms, Camp Pendleton, Las Vegas’s own army gunnery school, and other military bases, provided thousands of weekend visitors who patronized the casinos. Supplementing these groups were thousands more defense workers from nearby Basic Magnesium and from southern California’s defense plants.

This sudden surge in business sparked a furious casino boom, helped by reform mayor Fletcher Bowron’s campaign to drive professional gamblers out of Los Angeles. Beginning in 1938, they began fleeing to Las Vegas, bringing their valuable expertise with them. Former vice officer and gambler Guy McAfee opened the Pioneer Club downtown and the Pair-O-Dice on the Los Angeles Highway (later the Strip) before unveiling his classy Golden Nugget (with partners) in 1946. Las Vegas also drew the attention of organized crime figures. Bugsy Siegel and associate Moe Sedway came to town in 1941 at the behest of eastern gangsters who were anxious to capture control of local race wires, the telephone linking system for taking bets on horse races.

Fremont Street grew, as older establishments bordering its sidewalks yielded to modern-looking successors. But a more significant trend in the 1940s was the Strip’s development. The first major resort was the El Rancho Vegas, which revolutionized casino gambling. The brainchild of Thomas Hull, the hotel exemplified the formula he developed for the Strip’s success. In 1940, he amazed everyone by rejecting a downtown location for more spacious county lands in the desert just south of the city. In the old West, gambling had always been confined to riverboats and small hotels near some railroad or stagecoach station. With his El Rancho Vegas Hotel, Hull liberated gambling from its historic confines and placed it in a spacious resort hotel, complete with a pool, lush lawns and gardens, a showroom, an arcade of stores, and most important, parking for 400 cars. It was Hull, the southern Californian, who recognized that the highway (with its cars, trucks, and buses) rather than the railroad was the transportation wave of the future and that in the age of electric power, a downtown location was no longer superior to a suburban one.

For the most part, the El Rancho’s successors in the 1940s, such as the Hotel Last Frontier, the Flamingo, and Thunderbird, followed Hull’s model although with a larger and more plush format. The Flamingo, built by Bugsy Siegel and the Hollywood Reporter’s Billy Wilkerson, freed Las Vegas from the traditional Western motif slavishly followed by resorts such as the El Rancho and El Cortez downtown. With its Miami Beach–Monte Carlo ambience, the Flamingo opened a new world of thematic options for future resorts such as Caesars Palace and the Mirage.

The Strip assumed its familiar shape in the 1950s with the addition of eleven new resorts. Contributing to this growth was the liberalization of the nation’s tax laws, which now permitted substantial deductions for business travel for professional improvement or the exhibition of goods. Anxious to fill their hotel rooms during the week, Las Vegas and Clark County officials formed a convention and visitors board in 1955 and built the Las Vegas Convention Center behind the Riviera Hotel on land donated by Horseshoe Club owner Joe W. Brown. Beginning in 1959, this new meeting hall, with its proximity to the Strip, tended to divert delegates away from Fremont Street. The construction of a new airport in 1947–1948 south of what became the Tropicana Hotel and its enlargement into a modern jetport in 1962–1963 only intensified the trend away from downtown. Construction of Interstate 15 in the 1960s along the resort corridor’s west side, with five strategic exits compared to just one for downtown, contributed further to the flow of traffic to the emerging Strip.

In the 1960s, funding of the Southern Nevada Water project by Pres. Lyndon Johnson awarded the metropolitan area enough Lake Mead water to support a city of 2 million people, a vital prerequisite for the city’s future growth. In addition, passage of Gov. Paul Laxalt’s corporate gaming proposal in 1969 promoted the city’s future development by ending the traditional requirement that every stockholder be investigated. The new law limiting the licensing procedure to only “key executives” permitted the entry of Hilton, Hyatt, MGM, and other corporate giants into the state. Only these entities, with their access to large pools of capital, could afford the billions necessary to build the megaresorts that characterize Las Vegas today.

In the 1950s and 1960s, a number of new technological advances and social trends reinforced the city’s growth, leading to construction of spectacular newcomers such as Caesars Palace. Chief among these trends was the so-called middle-classification of the United States. In the postwar era, with more Americans graduating from high school and even college and with the postindustrial economy creating more high-paying white-collar jobs, both disposable and discretionary income – crucial to the budgets of gamblers and vacationers—soared. Moreover, income in California increased by more than the national average. Even blue-collar workers enjoyed substantial income gains. Las Vegas also benefited from the growth in automation and generous union contracts that gave workers more vacation and holiday time for leisure pursuits. In addition, the introduction of the credit card by Diner’s Club in 1950 and arrival of the first commercial passenger jets in 1957 not only expanded Las Vegas’s market zone to the East Coast, Europe, and Asia, but also eliminated the need to travel with large amounts of cash. These innovations, along with automated teller machines, debit card, and computers, all made long-distance travel easier, liberating Las Vegas from its dependence upon southern California.

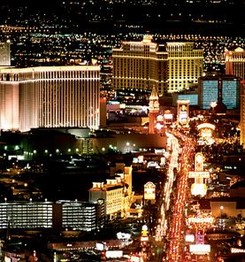

Following a brief recession occasioned by the debut of Atlantic City, which temporarily siphoned off some of Las Vegas’s East Coast market, the city rebounded in the 1980s and 1990s. In what has been Las Vegas’s most spectacular round of expansion, a new generation of casino executives epitomized by Steve Wynn joined an older group led by Kirk Kerkorian to transform the casino city into a major resort destination. Several factors contributed to the metropolitan area’s mercurial growth. First was the construction of several lavish new hotels. The $630 million Mirage set a record for cost when it opened in 1989 and instantly became the state’s leading tourist attraction, usurping the title held by Hoover Dam for over five decades. Quickly eclipsing the Mirage’s price tag was Kirk Kerkorian’s 1993 MGM Grand Hotel and Theme Park, which at nearly $1 billion was the most expensive hotel ever built. Steve Wynn, however, upped the ante almost immediately by imploding the Dunes Hotel and replacing it with the $1.6 billion Bellagio. At the same time, former COMDEX Convention mogul Sheldon Adelson took over the venerable Sands Hotel and demolished it to make way for the Venetian, a $1.5 billion Renaissance successor. These and other city-themed resorts such as New York–New York and Hilton’s Paris combined with Circus Circus’s upscaled properties embodied by Luxor and Mandalay Bay to transform the Strip into an even greater tourist Mecca.

The second factor went beyond the money, the new restaurants, and bigger and grander casinos. Wynn helped pioneer a new approach to luring additional visitors to Las Vegas when he introduced the concept of offering special attractions both inside and outside his casino. The Mirage initiated the idea in 1989 with its erupting volcano, white tigers, and bottlenosed dolphins; Wynn continued the trend with his outdoor pirate battle at Treasure Island and Bellagio’s “dancing fountains”. MGM’s theme park, Paris’s Eiffel Tower, the Stratosphere, and the Las Vegas Hilton’s Star Trek Experience only added to the fare.

A number of other themes have also characterized Las Vegas’s efforts to broaden its market, among which has been an appeal to families. This trend actually dates from the 1950s when the Hacienda’s Warren and Judy Bayley pursued the niche by offering guests multiple swimming pools and a quarter-midget go-cart track. In the 1970s, new Circus Circus proprietors William Bennett and William Pennington took their casino’s clown theme and applied it to families rather than to high rollers as the original owner had tried to do. They added a carnival midway of games, candy stands, and toy shops and later supplemented it with a domed, indoor amusement park packed with thrill rides. Circus Circus repeated this success in the 1990s with its Excalibur Hotel, a dazzling medieval castle priced to attract the low-end family market. But despite these and other efforts to soften Las Vegas’s image nationally, families have consistently represented no more than 8 percent of the town’s visitors.

A third factor was that in the 1980s and 1990s, Las Vegas gamers also acquired a substantial home market as the metropolitan area’s population skyrocketed from 273,000 in 1970 to more 1.3 million by century’s end. The first major neighborhood casinos catering primarily to locals came in the 1970s when Palace Station (1976) and Sam’s Town (1979) began operations. Reinforcing this market was the development of a new sector in the Las Vegas economy, the retirement industry. Following the deaths of gaming figures Del Webb (1973) and Howard Hughes (1976), their two companies joined forces to build what eventually became Sun City Summerlin. Since Hughes had purchased most of the outlying lands west of the city in the 1940s and Del Webb possessed the construction expertise to build homes, the companies formed a partnership and began work on Sun City in the mid-1980s. This project, along with its satellite communities, will ultimately contain more than 30,000 homes. Already, thousands of retirees have moved to Sun City and other small projects around the city. Las Vegas is the only place where they can not only “go to the malls” and engage in the traditional forms of leisure offered by Miami and Phoenix but also gamble on horses, sports, and cards.

In addition to these new flourishes, the casinos have pushed the addition of high-end retailing centers, such as the Forum Shops at Caesars Palace and its clones at the Venetian and elsewhere. The results have been nothing less than dramatic. As the twentieth-first century dawned, more spectacular resorts, world-class shopping, and special attractions had combined with the growing national and global popularity of casino gambling to make Las Vegas the leading tourist center in the United States—surpassing its nearest rival, Orlando.