Does gambling help the economy? This question has been asked over and over for generations. Economic scholars such as Paul Samuelson have suggested that since gambling produces no tangible product or required service, it is merely a “sterile” transfer of money. Therefore the energies (and all costs) expended in the activity represent unneeded costs to society. Further, he points out that gambling activity creates “inequality and instability of incomes” (Samuelson 1976, 425).

On the other hand, a myriad of economic impact studies have concluded that gambling produces jobs, purchasing activity, profits, and tax revenues. Invariably, these studies have been designed by, or sponsored by, representatives of the gambling industry. For instance, the Midwest Hospitality Advisors, on behalf of Sodak Gaming Suppliers, Inc., conducted an impact study of Native American casino gaming. Sodak had an exclusive arrangement to distribute International Gaming Technologies (IGT) slot machines to Native American gaming facilities in the United States. The report was “based upon information obtained from direct interviews with each of the Indian gaming operations in the state, as well as figures provided by various state agencies pertaining to issues such as unemployment compensation and human services”.

The study indicated that the Minnesota casinos had 4,700 slot machines and 260 blackjack tables in 1991. Employment of 5,700 people generated $78.227 million in wages, which in turn yielded $11.8 million in social security and Medicare payments, $4.7 million in federal withholding, and $1.76 million in state income taxes. The casinos spent over $40 million annually on purchases of goods from in-state suppliers. Net revenues for the tribes were devoted to community grants as well as to payments to members, health care, housing, and infrastructure. The report indicated that as many as 90 percent of the gamers in individual casinos were from outside Minnesota; however, there was no indication of the overall residency of the state’s gamblers.

The American Gaming Association (AGA) ignores the question of where the money comes from as it reports that “gaming is a significant contributor to economic growth and diversification within each of the states where it operates” (Cohn and Wolfe 1999, 7). An AGA survey talks of the jobs, tax revenues, and purchasing of casino properties in 1998: a total of 325,000 jobs, $2.5 billion in state and local taxes, construction and purchasing leading to 450,000 more jobs, and $58 million in charitable contributions for employees of casinos. The report indicates that the “typical casino customer” has a significantly higher income than the average American, with 73 percent setting budgets before they gamble (there was no indication about how many of these kept their budgets), making them a “disciplined” group. The report made no attempt to see if the players were local residents or not.

Likewise, another study sponsored by IGT and conducted by Northwestern University economist Michael Evans found that “on balance, all of the state and local economies that have permitted casino gaming have improved their economic performance” (The Evans Group 1996, 1–1). Evans found that in 1995, casinos had employed 337,000 people directly, with 328,000 additional jobs “generated by the expenditures in casino gambling”. State and local taxes from casinos amounted to $2 billion in 1995, and casinos yielded $5.9 billion in federal taxes. Yet Evans did not consider that the money for gambling came from anywhere, or that the money could have been spent elsewhere if it were not spent in casino operations, or that if spent elsewhere, it would also generate jobs and taxes. The studies by industry-sponsored groups also neglect the notion that there could be economic costs as a result of externalities to casino operations – namely, as a result of the increased presence of compulsive gambling behaviors and some criminal activity. Evans brushed aside the possibilities with a comment that “the sociological issues that are sometimes associated with gaming, such as the rise in pathological gamblers who ‘bet the rent money’ at the casinos, are outside the scope of this study. Nonetheless, it seems appropriate to remark at this juncture that occasional and anecdotal evidence does not prove anything”.

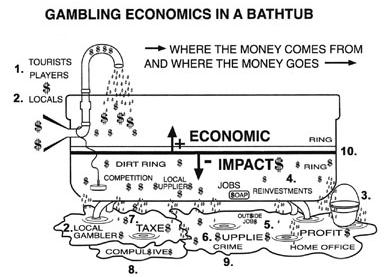

1–2. Source of Gambling Funds; 3. Profits to outside owners; 4. Profits reinvested in casino location; 5. Jobs; 6. Purchase of supplies; 7. Taxes; 8. The social cost of pathological gambling; 9. The costs of gambling-related crime; 10. The dirt ring – we don’t see it if the water level is rising.

Whatever is produced by a gambling enterprise does not come out of thin air; it comes from somewhere, and that “where” must be identified if we are to know the economic impacts of gambling operations. The impact studies commissioned by the gambling industry fall short.

So what is the impact of gambling activity upon an economy? This is a difficult question to answer, as the answer must contain many facets, and the answer must vary according to the kind of gambling in question as well as the location of the gambling activity. Although the question for specific gambling activity poses difficulties, the model necessary for finding the answers to the question is actually quite simple. It is an input-output model. Two basic questions are asked: (1) Where does the money come from? and Where does the money go? The model can be represented by a graphic display of a bathtub.

Water comes into a bathtub, and water runs out of a bathtub. If the water comes in at a higher rate than it leaves the tub, the water level rises; if the water comes in at a slower rate than it leaves, the water level is lowered. An economy attracts money from gambling activities. An economy discards money because of gambling activity. Money comes and money goes. If, as a result of the presence of a legalized gambling activity, more money comes into an economy than leaves the economy, there is a positive monetary effect because of the gambling activity. The level of wealth in the economy rises. If more money leaves than comes in, however, then there is a negative impact from the presence of casino gambling. Several factors must be considered in what I will call the Bathtub Gambling Economics Model. We must recognize the source of the money that is gambled by players and lost to gambling enterprises, and we must consider how the gambling enterprise spends the money it wins from players.

Factors in the Bathtub Gambling Economics Model

Tourist players: Are players/persons from outside the local economic region (defined geographically) – and are they persons who would not otherwise be spending money in the region if gambling activities were absent? A tourist’s spending brings dollars into the bathtub unless they otherwise would have spent the money in the region.

Local players: Are the players from the local regional economic area? If so, does the presence of gambling activities in the region preclude their travel outside the region in order to participate in gambling activities elsewhere? If they are locals who would not otherwise be spending money outside the region, their gambling money cannot be considered money added to the bathtub.

Additional player questions: Are the players affluent or people of little means? Are the players persons who are enjoying gambling recreation in a controlled manner, or are they playing out of control and subject to pathologies and compulsions?

Profits: Are the profits from the operations staying within the economic region, are they going to owners (whether commercial, tribal, or governments) who reside outside the economic region, or are they reinvested by the owners in projects that are outside of the region?

Reinvestments: Are profits reinvested within the economic region? Are gambling facilities expanded with the use of profit moneys? Are facilities allowed to be expanded?

Jobs: Are the employees of the gambling operations persons who live within the economic region? Are the casino executives of the companies who operate (or own) the facilities local residents?

Supplies: Does the gambling facility purchase its nonlabor supplies – gambling equipment (machines, dice, lottery and bingo paper), furniture, food, hotel supplies – from within the economic region?

Taxes: Does the facility pay taxes? Are profits leading to excessive federal income taxes? Are gambling taxes moderate or severe? Do the gambling taxes leave the economic region? Does the government return a portion of the gambling taxes to the region? How expensive are infrastructure and regulatory efforts that are required because of the presence of gambling that would not otherwise be required? Do the gambling taxes represent a transfer of funds between different economic strata of society?

Pathological gambling compulsive or problem gambling): How much pathological gambling is generated because of the presence of the gambling facility in the economic region? What percentage of local residents have become pathological gamblers? What does this cost the society – in lost work, in social services, in criminal justice costs?

Crime: In addition to costs caused by pathological gamblers, how much other crime is generated by gamblers because of the presence of a gambling facility? How much of this crime occurs within the economic region, and what is the cost of this crime for the people who live in the economic region?

The construction factor: If a gambling facility is a large capital investment, the infusion of construction money will represent a positive contribution to the economic region at an initial point. The investors must be reimbursed for the construction financing with repayments and interest over time, however. The long-range extractions of money from a region will more than balance the temporary infusions of money into a region. An application of the model must recognize that the incomes eventually produce outgoes. The examples that follow therefore ignore the construction factor—although more refined examples may see it as positive for initial years and negative thereafter.

Some Descriptive Applications of the Model

The Las Vegas Bathtub Model

The Las Vegas economy has witnessed phenomenal growth in the past few years. This has occurred even in the face of competition from around the nation and world, as more and more locations have casinos and casino gambling products. As of the end of 2000, the Las Vegas economy was strong because the overwhelming amount of gambling money (as much as 90 percent) brought to the casinos came from visitors. According to 1999 information from the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, visitors stay in Las Vegas an average of four days, spending much money outside of the casino areas. Las Vegas has money leakage as well. State taxes are very low, however, and much of the profits remains, as owners are local. Or if not, they see great advantages in reinvesting profits in expanded facilities in Las Vegas. The costs of crime and compulsive gambling associated with gambling are probably major; however, many of these costs are transferred to other economies, as most problem players return to homes located in other economic areas. Las Vegas is not a manufacturing or an agricultural region, so most of the purchases (except for gambling supplies) result in leakage to other economies. Gambling locations in Las Vegas such as bars, 7-11 stores, and grocery stores represent very faulty bathtubs—bathtubs with great leakage.

Other Jurisdictions in the United States

Atlantic City’s casino bathtub functions appropriately, as most of the gamblers are from outside the local area. Players are mostly “day-trippers”, however, who do not spend moneys outside the casinos. Most purchases, as with those in Las Vegas, result in leakage for the economy. Like those in Las Vegas, state gaming taxes are reasonably low. Other taxes, however, are high.

Most other U.S. jurisdictions do not have well-functioning bathtubs, because most offer gambling products, for the most part, to local players. Native American casinos may help local economies because they do not pay gambling excise taxes or federal income taxes on gambling wins, as they are wholly owned by tribal governments who keep profits (which are in the form tribal taxes) in the local economies.

Two Empirical Applications of the Model Illinois Riverboats.

In 1995, I participated in gathering research on the economic impacts of casino gambling in the state of Illinois (Thompson and Gazel 1996). Illinois has licensed ten riverboat operations in ten locations of the state. The locations were picked because they were on navigable waters and also because the locations had suffered economic declines. We interviewed 785 players at five of the locations. We also gathered information about the general revenue production of the casinos and the spending patterns of the casinos—wages, supplies, taxes, and residual profits. The casinos were owned by corporations; most of them were based outside of the state, and none of them were based in the particular casino communities.

The focus of our attention was the local areas within thirty-five miles of the casino sites. The data were analyzed collectively, that is, for all the local areas together.

In 1995, the casinos generated revenues of just over $1.3 billion. Our survey indicated that 57.9 percent of the revenues came from the local area, from persons who lived within thirty-five miles of the casinos. From our survey we determined, however, that 30 percent of these local gamblers would have gambled in another casino location if a casino had not been available close to their home.

Therefore, in a sense, their gambling revenue represented an influx of money to the area. That is, the casino blocked money that would otherwise leave the area. We considered a part of the local gambling money to be nonlocal money, in other words, visitor revenue. On the other side of the coin, as a result of our surveys, we considered that 22 percent of the visitors’ spending was really local moneys. Many of the nonlocal gamblers indicated that they would have come to the area and spent money (lodging, food, etc.), even if there were no casino in the area.

By interpolating the income for one casino from the total data collected, we envision a casino with $120 million in revenue. The share of these revenues that came from within the thirty-five-mile economic area (after adjustments for the 30 percent retained from other casino jurisdictions) equaled $60 million. In other words, we can represent this as local money lost to the casino. The question then is, how much of the money from the casino revenues of $120 million was retained in the thirty-five-mile area.

The direct economic impact was negative $8.367 million (that is, $60 million of revenues came from the local thirty-five-mile area, but only $51,632,200 of the spending was locally retained). A direct economic loss for the area of $8,367,800 may be multiplied by approximately two, as the money lost would otherwise have been able to circulate two times before leaving the area economy. The direct and indirect economic losses due to the presence of the gambling casino therefore equaled $16,735,600.

Added to these economic losses are additional losses due to externalities of social maladies. For each local area, there will be an increase in problem and pathological gambling, and there will also be an increase in crime due to the introduction of casino gambling. The presence of casino gambling, according to one national study (Grinols and Omorov 1996), added to the other social burdens of society, such as taxes, per-adult costs of $19.63 due to extra criminal activity and criminal justice system costs due to related crime. The National Gambling Impact Study Commission found that the introduction of gambling to a local area doubled the amount of problem and pathological gambling (National Gambling Impact Study Commission 1999, 4–4). Our studies of costs due to compulsive gambling find adults having to pay an extra $56.70 each because of extra pathological gamblers (0.9 percent of the population) and an extra $44.10 each because of extra problem gamblers (2 percent of the population). This additional $120.43 per adult translates into an extra loss of $12,043,000 (or $24,086,000 with a multiplier of two) for an economic area of 100,000 adults when the first casino comes to town.

The players’ interviews indicated that 37.2 percent were from the thirty-five-mile area surrounding the casino. Of their $44.64 million in gambling revenues, 20 percent is money that would otherwise be gambled elsewhere. On the other hand, 10 percent of the $75.36 million gambled by “outsiders” would have otherwise come to the area in other expenses by these players. Hence we consider that $43.248 million of the losses are from the local area and $76.752 million comes from the “outside”.

The positive local area economic impacts of Native American casinos in Wisconsin contrast to the negative impacts in Illinois for several reasons. The Illinois casinos are purposely put into urban areas as a matter of state policy. As a result, a higher portion of gamers are local residents; therefore, fewer dollars are drawn into the area. The urban settings also exacerbate social problems, as the negative social costs are retained in the areas. The two major factors distinguishing the positive from negative impacts are the fact that the Native casinos do not pay taxes to outside governments and the fact that the ownership of the casinos by local tribes keeps all the net profits (less management fees) in the local areas.

Other Forms of Gambling

The economic model can be applied to all forms of gambling. Other findings may arise from studies, however. For instance, for horse-race betting, there would have to be a realization that commercial benefits of racing are spun off to a horse breeding industry. Today those benefits could be seen merely in terms of dollars. In the past, however, those benefits were seen in terms of a valued national resource. Because breeding was encouraged, the nation’s stock of horses was improved in both quality and quantity, and that stock was a major military resource in times of war. Even though the Islamic religion condemned gambling as a whole, exceptions were made for horse-race betting precisely because it would provide incentives for “improving the breed.” Another consideration affecting race betting is the source of funds that are put into play by widely dispersed offtrack betting facilities, and then how those funds are distributed. The employment benefits of racetracks are also more difficult to put into a geographical context, as many employees work for stables and horse owners whose operations are far from the tracks.

Lotteries also draw sales from a wide geographic area. Funds are all given to government programs; however, the funds are often designated for special programs. The redistribution effects are difficult to trace and are dependent on the type of programs supported. When casino taxes are earmarked, the same problem exists; however, a casino tax will be much less than the government’s share of lottery revenues. Lotteries do not provide the same employment benefits for local communities as are provided by casinos, as they are not as labor intensive. Benefits from sales tend to go to established merchants, often large grocery chains, in the lottery jurisdiction.

National lottery games, such as Lotto America, only further complicate the economic formulas. Such is also the case with Internet gambling. For race betting and lotteries, there is very little activity by nonresident players.

What Do Negative Gambling Economic Impacts Mean for a Local Community?

Negative direct costs, imposed on an area by the presence of a casino facility, simply mean there can be no economic gains for the economy. There can be no job gains, only job losses. Purchasing power is lost in the community; local residents play the gambling dollars, and those residents do not have funds for other activities. Our survey of Wisconsin players found that 10 percent would have spent their gambling money on grocery store items if they had not visited the casino. One-fourth indicated they would have spent the money on clothing and household goods. Additionally, there can be no real government revenue gains, except at a very high cost imposed upon local residents in severely reduced purchasing powers and high social costs. Negative impacts simply mean the facilities are economically bad for an area.