The institution that we call the casino had its origins in central and western European principalities in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was here that governments gave concessions to private entrepreneurs to operate buildings in which games could be legally played in exchange for a part of the revenues secured by the entrepreneurs. Whereas from time immemorial, players had competed against one another in all sorts of private games, here games were structured to pit the player against the casino operators – known as the “house”. These gambling halls were designed to offer playing opportunities to an elite class in an atmosphere that allowed them to enjoy relaxation among their peers. Even though casinos in the United States seek to achieve goals that are primarily financial by offering gaming products to as many persons as possible, the notion of having a European casino often resonates where proponents meet to urge new jurisdictions to legalize casinos.

In some cases, casino advocates actually believe they can somehow duplicate European experiences, but rarely do they meet such goals, for a variety of reasons. If they indeed knew about the way European casinos operate, they would not want any of the experience repeated in casinos they controlled. Other times, they may actually try to establish some of the attributes of these casinos, only to realize later that the attributes are quite adverse to their primary goals—profits, job creation, economic development, or tax generation.

The European casino is offered in campaigns for legalization as an alternative to having a jurisdiction endorse Las Vegas–type casinos. In reality, however, it is the Las Vegas casino that the advocates of new casino legalizations in North America wish to emulate. Among all the casino venues in North America, Las Vegas best delivers on the promise of profits, job creation, economic development, and tax generation. Even though this encyclopedia is devoted to gambling in the Western Hemisphere, the imagery of the European casino is so often used in discussion of casino policy outside of Europe that a descriptive commentary is pertinent here.

In June 1986, I visited the casino that operates within the Kurhaus in Wiesbaden, Germany. In an interview, Su Franken, director of public relations for the casino, was describing a new casino that had opened in an industrial city a few hours away. With a stiff demeanor, he said, “They allow men to come in without ties, they have rows and rows of noisy slot machines, they serve food and drinks at the tables, and they are always so crowded with loud players; it is so awful.” Then with a little smile on his face, he added, “Oh, I wish we could be like that”.

The reality is that, even with the growth in numbers of casino jurisdictions and numbers of facilities, Europe cannot offer casinos such as we are used to in North America – those in Las Vegas and Atlantic City; the Mississippi riverboats; those operated by Canadian provincial governments or by Native American reservations – because a long history of events impedes casino development based upon mass marketing. Actually, the rival casino to which the Wiesbaden manager was referring, the casino at Hohensyburg near Dortmund, was really just a bigger casino, where a separate slot machine room was within the main building as opposed to being in another building altogether. Men usually had to wear ties, but the dress code was relaxed on weekends, and the facility had a nightclub, again in a separate area. It was crowded simply because it was the only casino near a large city, and the local state government did not enforce a rule against local residents’ entering the facility.

The casinos of Europe are very small compared to those in Las Vegas. The biggest casinos number their machines in the hundreds, not the thousands. A casino with more than twenty tables is considered large, whereas one in Las Vegas with twice that number would be a small casino. Even the largest casinos, such as those in Madrid, Saint Vincent (Italy), and Monte Carlo, have gaming floors smaller than the ones found on the boats and barges of the Mississippi River. The revenues of the typical European casino are comparable to those of the small slot machine casinos of Deadwood, South Dakota, or Blackhawk, Colorado. The largest casinos would produce gaming wins similar to those of average Midwestern riverboats.

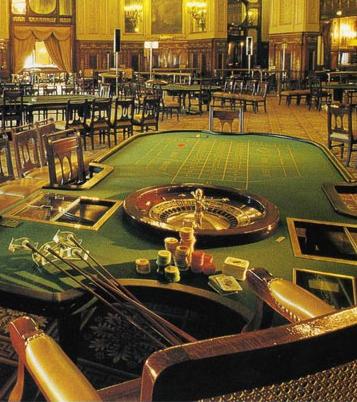

Baden Baden (Germany) – The most luxurious casino in the world.

Another distinguishing feature of the European casino is that most are local monopoly operations. Where casinos are permitted, a town or region will usually have only one casino. The government often has a critical role in some facet of the operation, either as casino owner (or directly or through a government corporation) or as owner of the building where the casino is located. Where the government does not own the casino, it might as well. Taxes are often so high that the government is the primary party extracting money from the operations. For example, some casinos in Germany pay a 93 percent tax on their gross wins. That means for every 100 marks the players lose to the casino, the government ends up with ninety-three marks. In France the top marginal tax rate is 80 percent; it is 60 percent in Austria and 54 percent in Spain. Nowhere are rates below the top 20–30 percent rates in U.S. jurisdictions (the Nevada rate is less than 7 percent—that is, for each $100 players lose to the casino, the government receives just $7 in casino taxes).

The European casinos typically restrict patron access in several ways. Several will not allow local residents to gamble. They require identification and register patron attendance. They have dress codes. Many permit players to ban themselves from entering the casinos as a protection from their own compulsive gambling behaviors. They also allow the families of players to ban individuals from the casinos. The casinos themselves also may bar compulsive gamblers. (5) The casinos operate with limited hours, usually evening hours. No casino opens its doors twenty-four hours a day. The casinos, as a rule, cannot advertise. If they can, they do so only in limited, passive ways. Credit policies are restrictive. Personal and payroll checks will not be cashed. (8) Alcoholic beverages are also restricted. In many casinos (for instance, all casinos in England), such beverages are not allowed on the gaming floors. Only rarely is the casino permitted to give drinks to players free of charge. (Other free favors such as meals or hotel accommodations or even local transportation are also quite rare.)

The clientele of the European casino is generally from the local region. Few of the casinos rely upon international visitors. Moreover, very few have facilities for overnight visitors, although several are located in hotels owned by other parties. The casinos feature table games, and where slot machines are permitted, they are typically found in separate rooms or even separate buildings. The employees at the casinos are usually expected to spend their entire careers at a single location. The employees are almost always local nationals.

There are myriad reasons why the European casino establishment has remained in the past, while modern casino development occurred in the United States, specifically in Las Vegas. First, Europe is a continent with many national boundaries. The future may see more and more economic and even political integration, but national separateness has been strong and will remain as a factor retarding casino development. The European Union has, at least at its initial stage of decision making, decided to allow casino policy to remain under the jurisdiction of its individual member states. Although a central congress may decree that all European states must standardize other products, usually following the most widely attainable and profitable standards, there will be no decrees that the entire continent should follow the most liberal casino laws. Each country retains sovereignty in this area.

Language and religious differences separate the various nations of Europe. No European congress can decree away these differences. National rules of casino operation have emphasized that entrepreneurs and employees be local residents. Such rules remain in place in most jurisdictions. In the past, movement of capital has been restricted among the states, making the possibilities of accumulating large investments for large resort facilities and for large promotional budgets difficult. Additionally, it was difficult for players to move their gaming patronage across borders, as they also would have to be able to move capital with that patronage. Advertisement restrictions also tied casino entrepreneurs to local markets. These small local markets never beckoned as attractive opportunities for foreign investors even when they could move funds.

Second, employment practices have not fostered the kind of cross-germination that is present in the North American casino industries. Typically, the employees of European casinos are local residents, and they are expected to stay with one casino property for an entire career. Promotions come from within. The work group is very personal in its interrelationships. The work group is also unionized and derives much of its wage base from tips given by players at traditional table games. The employment force is simply not a source for innovative ideas.

Third, as almost all of the casinos are monopoly businesses, the industry has had little incentive to develop competitive energies that could be translated into innovations. Also, the entrepreneurs have not been situated to take advantage of the forces of synergy, which are quite obvious in the Las Vegas and the U.S. gaming industry.

Fourth, the basic political philosophy that dominates government policymaking in Europe has its roots in notions of collective responsibility. Americans threw off the yoke of feudalism and its class system of noblesse oblige when the first boats of immigrants reached its Atlantic shores in the seventeenth century. The colonies fostered a spirit of individualism. Conversely, a spirit of feudalism persists in European politics. Remnants of monarchism remain, as the state has substituted official action for what was previously upper-class obligation. Socialist policies now ensure that the working classes will have their basic needs guaranteed. The government is the protector as far as personal welfare is concerned, and those protecting personal welfare (that is, the government officials) also are expected to guide personal behavior, even to the point of protecting people from their own weaknesses.

In the United States, and especially in the American West, the expectation was that people would control their own behaviors; such was not the case in Europe. In Europe, but not in the United States, viable Socialist parties developed. Coincidentally, Christian parties also developed. They too fostered notions that the state was a guardian of public morals. Christian parties saw casinos as anathema to the public welfare and permitted their existence only if they were small and restricted. Socialists also saw casinos as exploiting-bourgeois enterprises that had to be out-of-bounds for working-class people.

Fifth, and perhaps the overriding force against commercial development of casinos, there has been an almost perpetual presence of wartime activity in Europe over the past three centuries. The many borders of Europe have caused a constant flow of national jealousies, alliances, and realignments, all of which contributed to one war after another. Often the wars engulfed the entire continent: the Napoleonic wars, the Franco-Prussian wars, and World Wars I and II. A modern casino industry cannot flourish amid wartime activity. Casinos need a free flow of people as customers, and people cannot move freely during wartime. Casinos need markets of prosperous people, but personal prosperity is disrupted for the masses during wartime. Wartime destruction consumes the resources of society. Moreover, a society does not allow its capital resources to be expended on leisure activities when the troops in the field need armaments. And wars change boundaries, governments, and rules. Casinos need stability in the economy and in political policy in order to grow; Europe has lacked stability over the last three centuries.

The United States has benefited from not being a war battlefield for over a century. Following World War II, the new industrial giant of the world accepted an obligation to help European countries rebuild their industrial and commercial bases. The Marshall Fund was created to infuse U.S. capital into European redevelopment. The Marshall Fund could have been a vehicle for infusing the individualistic American spirit of capitalism into European commercial policy as well. The fund stipulated, however, that the new and revitalized businesses of Europe had to be controlled by Europeans. U.S. entrepreneurs were not allowed into fund-supported businesses. The fund actually supported the reopening of a casino at Travemunde, Germany. But the policy of the U.S. government in not allowing Americans to directly participate in the commercial enterprise of rebuilding Europe blocked U.S. casino operators from legitimately entering Europe with the modern spirit they were utilizing in Las Vegas gambling establishments. On the other hand, less than fully legitimate Americans sought to bring slot machines to the continent. They were rooted out, however, and as these “operators” were deported, the image of the slot machine as a “gangster’s device” became firmly rooted into casino thinking in Europe.

The impacts of these many forces are felt today even though the existence of the forces is not as strong. There is much expansion of casino gambling in Europe. It is generally an expansion in the number of facilities, however, not in the size or scope of the facilities. Each of the former Eastern Bloc countries now has a casino industry, but restrictions on size and the manner of operations are severe, as are tax requirements. France authorized slot machines for its casinos for the first time in 1988. But a decade later, its largest casinos were producing revenues less than those of a typical Midwest riverboat, revenues measured in the tens of millions of dollars—nowhere near the hundreds of millions won by the largest Las Vegas and Atlantic City casinos. In Spain, casino revenues have been flat as the industry begs the government for tax relief. Austria has developed a megacasino at Baden bi Vien, but it would be almost unnoticeable on the Las Vegas Strip. Casinos Austria and Casinos Holland, two quasi-public organizations, are viewed as two of the leading casino entrepreneurs of the continent. But both derive much of their revenue from operations of casinos either on the sea or in Canada. Twenty Las Vegas and a dozen Native American properties exceed the revenues of the leading casinos in Germany.

The European casinos have a style that would be welcomed by many North American patrons. In achieving that style, however, the casinos must forfeit what most entrepreneurs, governments, and citizens want from casinos—profits, jobs, economic development, and tax generation.